by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

September 10, 2023

What is endometrial serous carcinoma?

Endometrial serous carcinoma is a type of cancer that starts in a part of the uterus called the endometrium. Endometrial serous carcinoma is an aggressive type of cancer that commonly spreads to other parts of the body. It is more common in women over 50 years of age. Another name for this type of cancer is uterine serous carcinoma.

Where does endometrial serous carcinoma start?

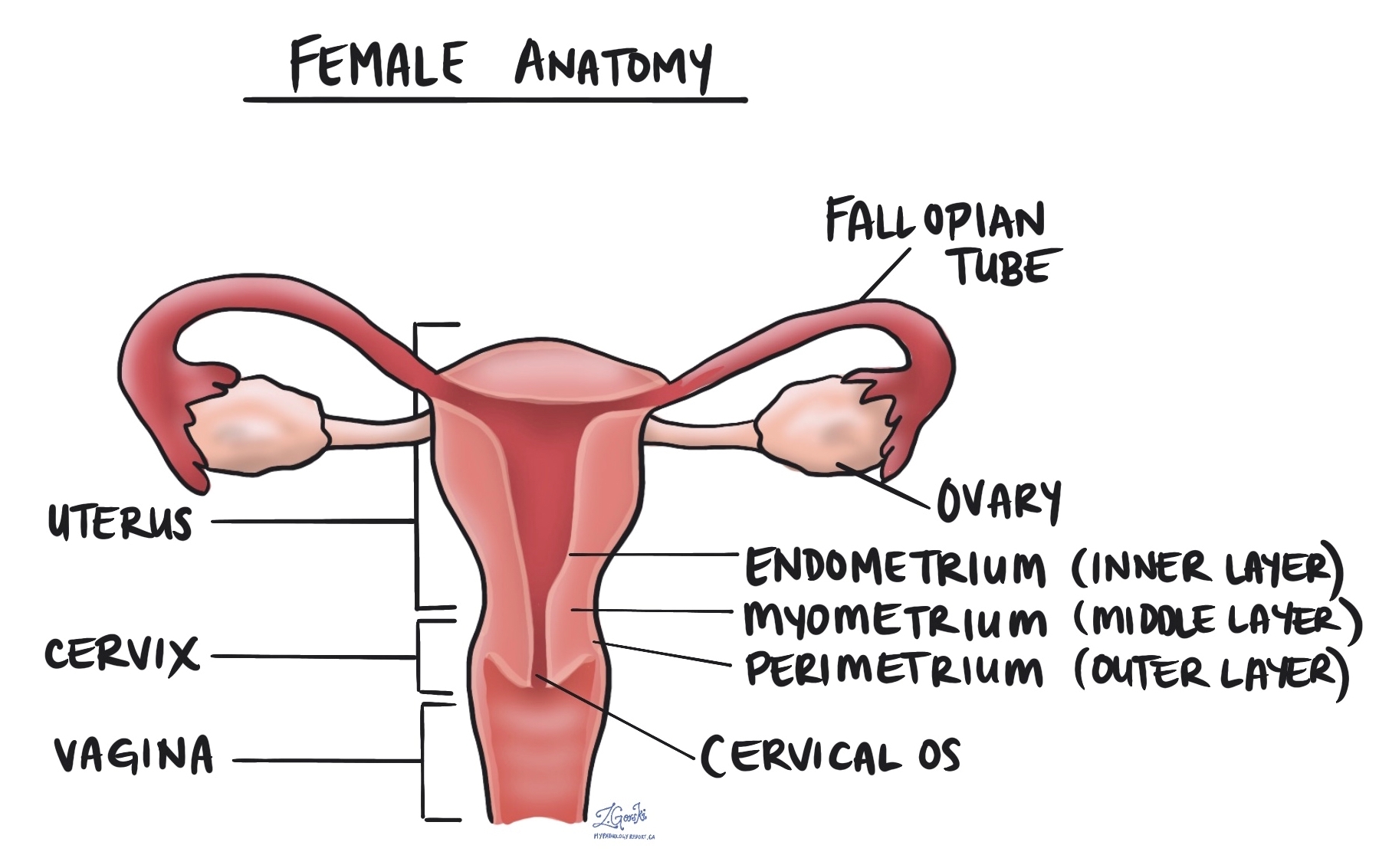

Endometrial serous carcinoma starts from glandular cells normally found in the endometrium, the thin layer of tissue that covers the inside of the uterus. The endometrium surrounding the tumour often shows a normal age-related change called atrophy. This cancer can also start within a common non-cancerous growth called an endometrial polyp.

Which precancerous conditions increase the risk of developing endometrial serous carcinoma?

Endometrial serous carcinoma is believed to develop from a precancerous disease called serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma.

What are the symptoms of endometrial serous carcinoma?

The most common symptom of endometrial serous carcinoma is abnormal post-menopausal bleeding.

What causes endometrial serous carcinoma?

The cause of endometrial serous carcinoma is currently unknown.

How is endometrial serous carcinoma diagnosed?

Endometrial serous carcinoma of the uterus is usually diagnosed after a small sample of tissue is taken from the endometrium in a procedure called a biopsy or curettage. The tissue is then sent to a pathologist for examination under a microscope. After the diagnosis, the tumour is removed along with the uterus in a surgical procedure called a hysterectomy.

What does endometrial serous carcinoma look like under the microscope?

When examined under the microscope, endometrial serous carcinoma is typically made up of tumour cells that look very abnormal compared to the healthy, noncancerous cells found in the endometrium. The tumour cells may be described as pleomorphic because they vary in shape, colour, and size throughout the tumour. The tumour cells can connect together to form round structures called glands or long, thin finger-like structures called papillae. A similar pattern of growth called micropapillary may also be seen. Mitotic figures (cells dividing to create new cells) are usually frequently seen.

What does myometrial invasion mean and why is it important?

All endometrial serous carcinomas start from a layer of tissue on the inside of the uterus called the endometrium. The myometrium is a thick band of muscle just below the endometrium. The spread of tumour cells from the endometrium into the myometrium is called myometrial invasion. The amount of myometrial invasion will be described in millimetres and as a percentage of the total myometrial thickness. Myometrial invasion is an important prognostic factor and is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

What is the cervical stroma and why is it important?

The cervix is a structure at the very bottom of the uterus. The cervix connects directly with the endometrium. The wall of the cervix is made up of a type of tissue called the stroma. Endometrial serous carcinoma may grow from the endometrium into the cervix. After the tumour is removed completely, your pathologist will carefully examine the tissue from the cervix to see if there are any tumour cells in the cervical stroma. This examination is important because finding tumour cells in the cervical stroma increases the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

Has the tumour spread into any other organs outside of the uterus?

Several other organs are directly attached or are very close to the uterus including the ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina, bladder, and rectum. A tumour that spreads directly into any of these organs is associated with a poor prognosis and will be described in your report.

What does lymphovascular invasion mean and why is it important?

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells were seen inside a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. The lymphatic vessels connect with small immune organs called lymph nodes that are found throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because cancer cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other parts of the body such as lymph nodes or the lungs.

Were lymph nodes examined and did any contain cancer cells?

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour to lymph nodes through small vessels called lymphatics. For this reason, lymph nodes are commonly removed and examined under a microscope to look for cancer cells. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to another part of the body such as a lymph node is called a metastasis.

Cancer cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour although lymph nodes far away from the tumour can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are only typically removed if they are enlarged and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancer cells in the lymph node.

If any lymph nodes were removed from your body, they will be examined under the microscope by a pathologist and the results of this examination will be described in your report. Most reports will include the total number of lymph nodes examined, where in the body the lymph nodes were found, and the number (if any) that contain cancer cells. If cancer cells were seen in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) will also be included.

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy is required.

What does it mean if a lymph node is described as positive?

Pathologists often use the term “positive” to describe a lymph node that contains cancer cells. For example, a lymph node that contains cancer cells may be called “positive for malignancy” or “positive for metastatic adenocarcinoma”.

What does it mean if a lymph node is described as negative?

Pathologists often use the term “negative” to describe a lymph node that does not contain any cancer cells. For example, a lymph node that does not contain cancer cells may be called “negative for malignancy” or “negative for metastatic adenocarcinoma”.

What are isolated tumour cells (ITCs)?

Pathologists use the term ‘isolated tumour cells’ to describe a group of tumour cells that measures 0.2 mm or less and is found in a lymph node. If only isolated tumour cells are found in all the lymph nodes examined, the pathologic nodal stage is pN1mi.

What is a micrometastasis?

A ‘micrometastasis’ is a group of tumour cells that measures from 0.2 mm to 2 mm and is found in a lymph node. If only micrometastases are found in all the lymph nodes examined, the pathologic nodal stage is pN1mi.

What is a macrometastasis?

A ‘macrometastasis’ is a group of tumour cells that measures more than 2 mm and is found in a lymph node. Macrometastases are associated with a worse prognosis and may require additional treatment.

What are mismatch repair proteins?

Mismatch repair (MMR) is a system inside all normal, healthy cells for fixing mistakes in our genetic material (DNA). The system is made up of different proteins and the four most common are called MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2.

The four mismatch repair proteins MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2 work in pairs to fix damaged DNA. Specifically, MSH2 works with MSH6 and MLH1 works with PMS2. If one protein is lost, the pair cannot function normally. A loss of one of these proteins increases the risk of developing cancer.

Pathologists order mismatch repair testing to see if any of these proteins are lost in a tumour. If mismatch repair testing has been ordered on your tissue sample, the results will be described in your pathology report.

How do pathologists test for mismatch repair proteins?

The most common way to test for mismatch repair proteins is to perform a test called immunohistochemistry. This test allows pathologists to see if the tumour cells are producing all four mismatch repair proteins.

If the tumour cells are not producing one of the proteins, your report will describe this protein as “lost” or “deficient”. Because the mismatch repair proteins work in pairs (MSH2 + MSH6 and MLH1 + PMS2), two proteins are often lost at the same time.

If the tumour cells in your tissue sample show a loss of one or more mismatch repair proteins, you may have inherited Lynch syndrome and should be referred to a genetic specialist for additional tests and advice.

What is the pathologic stage for endometrial serous carcinoma?

The pathologic stage for endometrial serous carcinoma is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system originally created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT)

Endometrial serous carcinoma is given a tumour stage (pT) between 1 and 4 based on the depth of myometrial invasion and growth of the tumour outside of the uterus.

- T1 – The tumour only involves the uterus.

- T2 – The tumour has grown to involve the cervical stroma.

- T3 – The tumour has grown through the wall of the uterus and is now on the outer surface of the uterus OR it has grown to involve the fallopian tubes or ovaries.

- T4 – The tumour has grown directly into the bladder or the colon.

Nodal stage (pN)

Endometrial serous carcinoma is given a nodal stage (pN) from 0 to 2 based on the examination of lymph nodes from the pelvis and abdomen.

- N0 – No tumour cells were found in any of the lymph nodes examined.

- N1mi – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node from the pelvis but the area with tumour cells was not larger than 2 millimetres (only isolated tumour cells or micrometastasis).

- N1a – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node from the pelvis and the area with tumour cells was greater than 2 millimetres (macrometastasis).

- N2mi – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node outside the pelvis but the area with tumour cells was not larger than 2 millimetres (only isolated cancer cells or micrometastasis).

- N2a – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node outside the pelvis and the area with tumour cells was greater than 2 millimetres (macrometastasis).

- NX – No lymph nodes were sent for examination.

Metastatic stage (pM)

Endometrial serous carcinoma is given a metastatic stage (pM) of 0 or 1 based on the presence of tumour cells at a distant site in the body (for example the lungs). The metastatic stage can only be determined if tissue from a distant site is submitted for pathological examination. Because this tissue is rarely present, the metastatic stage cannot be determined and is listed as MX.