by Catherine Forse MD FRCPC and Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

July 24, 2025

Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is a type of cancer that develops from gland-forming cells in an area of abnormal tissue called intestinal metaplasia. These cells are not normally found in the esophagus but can appear when the lining of the esophagus is repeatedly exposed to stomach acid.

This cancer almost always starts in the lower part of the esophagus, near where it joins the stomach (called the esophagogastric junction). It may also extend into the upper part of the stomach. Less commonly, adenocarcinoma can occur in the middle or upper esophagus, especially in areas where small patches of glandular cells are present.

What are the symptoms of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus?

Symptoms of esophageal adenocarcinoma often include difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), heartburn or acid reflux, weight loss, chest or abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting. In some cases, the cancer is discovered when investigating anemia or after imaging tests.

What causes adenocarcinoma of the esophagus?

Most cases of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus develop in people with a condition called Barrett esophagus. This condition is caused by long-standing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which allows acid and bile from the stomach to damage the lining of the esophagus over time.

In Barrett esophagus the normal squamous cells that line the esophagus are replaced by glandular cells that resemble those found in the intestines. This type of change is called intestinal metaplasia.

Over time, these abnormal glandular cells can acquire additional changes and progress to dysplasia, which is a precancerous condition. If left untreated, dysplasia may eventually lead to the development of invasive adenocarcinoma.

In the esophagus, dysplasia is classified into two main types:

-

Low grade dysplasia: The cells look abnormal but are still partially organized. This type of dysplasia has a lower risk of progressing to cancer, but careful monitoring or treatment is often recommended.

-

High grade dysplasia: The cells appear very abnormal and disorganized. High grade dysplasia has a much higher risk of turning into adenocarcinoma and often exists right next to or even within small areas of cancer.

Your pathology report may mention dysplasia if it was seen in the tissue sample. If high grade dysplasia is present alongside adenocarcinoma, it suggests that the cancer likely developed from a pre-existing area of Barrett esophagus. However, in some cases, especially when the tumor is large or deeply invasive, any surrounding dysplasia may no longer be visible.

Other risk factors for this type of cancer include obesity, smoking, male sex, and older age. The cancer is much more common in men than in women and occurs most often in people over the age of 60.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is usually made after a procedure called an upper endoscopy (or gastroscopy). During this procedure, a doctor uses a thin, flexible camera to examine the inside of the esophagus and take small tissue samples called biopsies. These samples are then examined under a microscope by a pathologist, who looks for cancer cells and confirms the diagnosis.

If cancer is found, additional tests such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), CT scan, or PET scan may be performed to assess how far the tumor has spread and to help plan treatment.

What does adenocarcinoma look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, adenocarcinoma is made up of abnormal gland-forming cells. Pathologists may describe different patterns such as tubular, papillary, mucinous, or signet ring cell. The most common type is tubular. These patterns are not separate subtypes but describe how the cancer cells are arranged. In some cases, more than one pattern may be seen in the same tumor.

If Barrett esophagus or dysplasia is present near the tumor, this may also be included in your report.

Tumor grade

The grade describes how closely the cancer cells look like normal gland-forming cells when viewed under the microscope. This is also called the histologic grade. The grade gives your doctor important information about how quickly the tumor is likely to grow and how likely it is to spread.

Pathologists divide esophageal adenocarcinoma into three grades:

Grade 1 – Well differentiated adenocarcinoma

In this type of tumor, more than 95% of the cancer cells form well-organized glands. These tumors usually grow more slowly and are less likely to spread. This is considered the lowest grade and is associated with a better prognosis.

Grade 2 – Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma

In moderately differentiated tumors, between 50% and 95% of the cancer cells form glands. These tumors show more variation in how the cells look and behave compared to grade 1. They tend to grow faster and are more likely to spread than well differentiated tumors.

Grade 3 – Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated adenocarcinoma

These tumors form glands in less than 50% of the cancer. In some cases, no gland formation is seen at all. The cells look very abnormal and behave aggressively. Poorly differentiated and undifferentiated tumors grow quickly and are more likely to spread to lymph nodes or distant parts of the body. These are considered high-grade tumors and are associated with a worse prognosis.

What does invasion mean in esophageal adenocarcinoma?

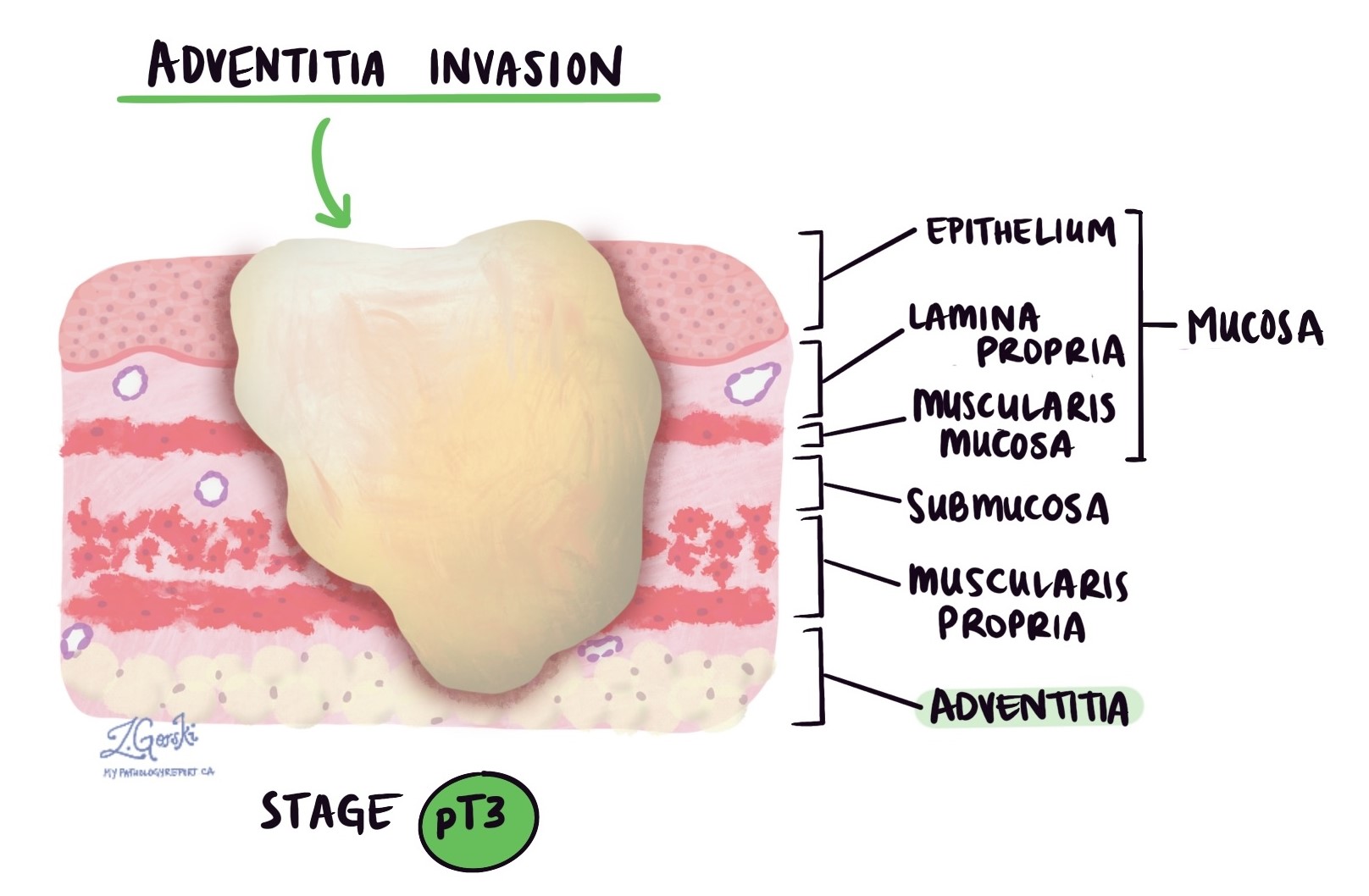

Invasion refers to how deeply the cancer has grown into the wall of the esophagus or surrounding tissues. Esophageal adenocarcinoma starts from gland-forming cells in the mucosa, the innermost layer of the esophagus. As the tumor grows, it can invade deeper layers of tissue and potentially spread to nearby organs.

The wall of the esophagus is made up of several distinct layers:

-

Mucosa – The thin inner lining where the tumor usually begins.

-

Submucosa – A supportive layer just beneath the mucosa.

-

Muscularis propria – A thick muscle layer that helps move food through the esophagus.

-

Adventitia – The outer connective tissue that anchors the esophagus in place. Unlike some other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, the esophagus does not have a serosa.

As the tumor grows, it can spread through these layers. In more advanced cases, it may invade nearby structures such as the trachea (windpipe), aorta, or pericardium (tissue around the heart).

Pathologists carefully examine the tumor under the microscope to find the deepest point of invasion, which is the layer the tumor has reached farthest into. This deepest point is very important because it determines the pathologic tumor stage, also called the pT stage, which is part of the TNM staging system used to describe how far the cancer has spread.

Pathologic tumor stage for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus

pT1: The cancer is in the very early stage and has grown only into the inner layers of the esophagus. These layers include the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa, which are just beneath the surface lining (mucosa).

pT1a: The cancer is even more limited and is found only in the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae—thin layers just below the surface of the esophagus.

pT1b: The cancer has grown deeper, into the submucosa, which is the layer of connective tissue just beneath the mucosa.

pT2: The cancer has reached the muscularis propria, a thick muscle layer that helps push food through the esophagus.

pT3: The cancer has grown through the muscle layer and reached the adventitia, which is the outermost covering of the esophagus.

pT4: The cancer has spread beyond the wall of the esophagus into nearby organs or structures.

pT4a: The cancer is growing into nearby areas such as the pleura (lining around the lungs), pericardium (lining around the heart), azygos vein, diaphragm, or peritoneum (lining of the abdomen). These tumors may still be removable with surgery.

pT4b: The cancer has spread into more critical nearby structures such as the aorta (a major blood vessel), vertebral body (bones of the spine), or airways. These tumors are usually considered more advanced and may not be removable with surgery.

HER2

HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) is a protein that helps cells grow and divide. In some esophageal cancers, the HER2 gene becomes overactive and produces too much of the HER2 protein. This is called HER2-positive cancer.

HER2-positive esophageal cancers tend to grow faster and may be more aggressive. However, targeted therapies like trastuzumab (Herceptin) can be very effective in treating these cancers. Knowing your tumor’s HER2 status helps your doctors decide if these targeted treatments should be part of your care plan.

How is HER2 tested?

Two tests are commonly used to check HER2 status:

-

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) – Measures the amount of HER2 protein on the surface of cancer cells.

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) – Measures the number of HER2 gene copies in the cancer cells.

HER2 immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC is a laboratory test that uses special stains to detect HER2 protein on the surface of tumor cells. Pathologists examine the stained tissue under a microscope and assign a score:

-

0 (negative) – No HER2 protein seen. This is considered HER2-negative, and targeted HER2 therapy is not usually helpful.

-

1+ (negative) – Weak or faint staining. Also considered HER2-negative.

-

2+ (equivocal or borderline) – Moderate staining. The result is unclear, and a second test (FISH) is needed.

-

3+ (positive) – Strong staining. This is HER2-positive, and patients may benefit from HER2-targeted therapy.

HER2 fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

If the IHC result is 2+ (equivocal or borderline), your pathologist may perform a FISH test to look more closely at the HER2 gene inside the tumor cells. This test uses special fluorescent markers that glow under the microscope to show how many HER2 gene copies are present.

-

Positive (amplified) – Too many HER2 gene copies. The cancer is HER2-positive and may respond well to HER2-targeted therapy.

-

Negative (non-amplified) – A normal number of HER2 gene copies. This means the cancer is HER2-negative, and HER2-targeted therapy is unlikely to help.

Sometimes, your report may include additional details like a HER2-to-chromosome ratio or the average number of HER2 gene copies per cell. These numbers help confirm the HER2 status more precisely.

Mismatch repair (MMR) protein testing

MMR proteins are part of the body’s system for fixing DNA errors that naturally occur when cells divide. The four main MMR proteins are MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6. If one or more of these proteins are missing or not working properly, DNA errors can build up, leading to cancer.

Pathologists test for MMR proteins using a method called immunohistochemistry (IHC). This test helps determine whether the DNA repair system in your cancer cells is working normally.

What do the results mean?

-

Normal (intact) – All four MMR proteins are present. This means the tumor is MMR-proficient, and the DNA repair system appears normal.

-

Abnormal (loss of expression) – One or more MMR proteins are missing. This is called MMR-deficient, and it has two important implications:

-

Your cancer may respond better to immunotherapy.

-

You may have a genetic condition called Lynch syndrome, which increases the risk of several types of cancer. Further genetic testing may be recommended.

-

PD-L1 testing

PD-L1 is a protein that some cancer cells use to hide from the immune system. By producing PD-L1, these cells avoid being attacked by immune cells. Immunotherapy drugs, called immune checkpoint inhibitors, work by blocking this signal so the immune system can find and destroy the cancer.

To see if immunotherapy might work, pathologists test for PD-L1 using a score called the Combined Positive Score (CPS). CPS compares the number of PD-L1-producing cells (both cancer cells and nearby immune cells) to the total number of tumor cells.

What do the results mean?

-

Positive (CPS ≥ 1) – PD-L1 is present. Immunotherapy may be an effective treatment option.

-

Negative (CPS < 1) – Very little or no PD-L1 is present. Immunotherapy is less likely to work, although it may still be considered in some situations.

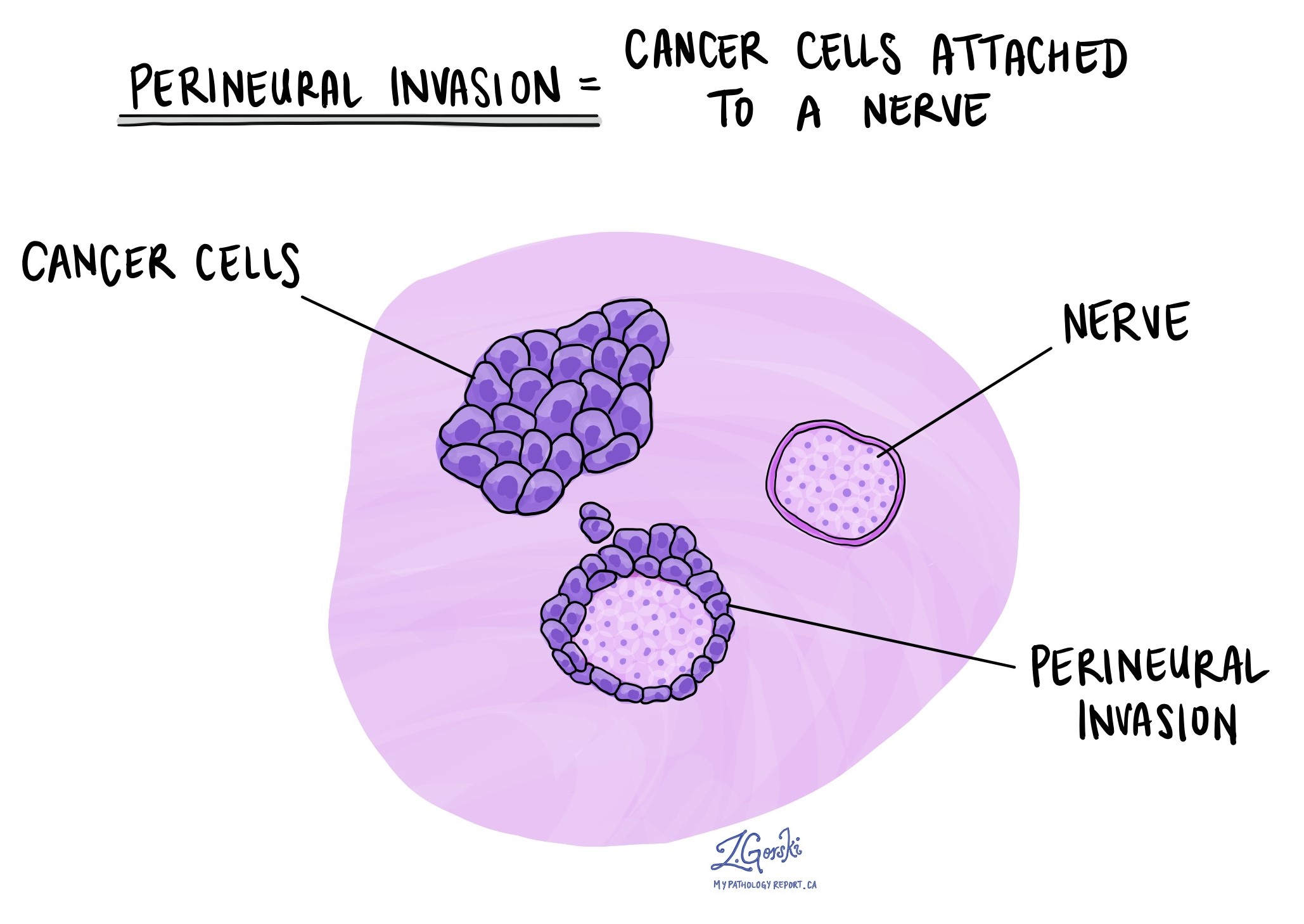

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion (PNI) means that cancer cells are seen growing along or around a nerve. Nerves are important structures that carry signals between the brain and the rest of the body. In the esophagus, nerves travel through the tissue surrounding the tumor.

Pathologists look carefully at the tissue under a microscope to identify cancer cells wrapping around the outer surface of a nerve or invading into the nerve itself. The presence of PNI is considered an aggressive feature because it shows that the cancer is invading local structures and may be more likely to come back after treatment or spread to other areas.

If PNI is seen, it will be described in your pathology report as “positive” or “present.” If no perineural invasion is found, the report will say “negative” or “absent.”

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means that cancer cells have entered small blood vessels or lymphatic vessels near the tumor in the esophagus. Blood vessels carry oxygen and nutrients to and from the tissues, while lymphatic vessels help drain fluid and carry immune cells. Both types of vessels can provide pathways for cancer cells to travel to other parts of the body.

When pathologists examine the tissue under the microscope, they look for clusters of cancer cells inside the thin-walled spaces that line these vessels. Special stains, called immunohistochemistry, may be used to help confirm the presence of tumor cells inside the vessels.

LVI is an important finding because it increases the risk that the cancer will spread to lymph nodes or other organs. If LVI is seen, it will be reported as “present” or “positive.” If no cancer is found in the vessels, the report will say “absent” or “negative.” The presence of LVI may influence your treatment plan, such as the need for chemotherapy or radiation after surgery.

Margins

In cancer surgery, margins are the edges of tissue that are cut to remove the tumor. After the tumor is removed, a pathologist examines the margins under a microscope to see if any cancer cells are present at the edge of the tissue.

The goal of surgery is to remove the entire tumor with a rim of normal tissue around it. If cancer cells are seen at the edge, it may mean that some cancer was left behind in the body. Your pathology report will describe the margins as either:

-

Negative (clear or uninvolved) – No cancer cells are found at the edge of the tissue. This suggests that the tumor was completely removed.

-

Positive (involved) – Cancer cells are present at the edge of the tissue. This may mean that cancer remains in the body and additional treatment may be needed.

Depending on the surgery and the location of the tumor, different margins may be described:

Depending on the surgery and the location of the tumor, different margins may be described:

-

Mucosal (lateral) margin – The inside surface of the esophagus next to the tumor.

-

Deep margin – Tissue underneath the tumor, deeper in the esophageal wall.

-

Proximal margin – The top edge of the removed tissue, closer to the mouth.

-

Distal margin – The lower edge, closer to the stomach.

-

Radial margin – The outer surface of the esophagus, especially important in tumors that may have grown through the esophageal wall into nearby tissues.

Your report will list each of these margins and whether or not cancer was found at the edge.

Lymph nodes and pathologic nodal stage (pN)

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped organs that are part of the immune system. They help filter substances from the body and play a role in fighting infections and cancer. Cancer cells can spread from the original tumor in the esophagus to nearby lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels. This process is called metastasis.

During surgery for esophageal adenocarcinoma, nearby lymph nodes are often removed and examined under a microscope to see if they contain cancer cells. Your pathology report will describe whether each lymph node is:

-

Positive – Cancer cells are found in the lymph node.

-

Negative – No cancer cells are seen in the lymph node.

The number of lymph nodes that contain cancer is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN), which is part of cancer staging and helps your doctor assess the extent of disease and choose the best treatment.

Pathologic nodal stages for esophageal adenocarcinoma:

-

pN0 – No cancer in any lymph nodes.

-

pN1 – Cancer found in 1 or 2 lymph nodes.

-

pN2 – Cancer found in 3 to 6 lymph nodes.

-

pN3 – Cancer found in 7 or more lymph nodes.

-

pNX – No lymph nodes were submitted or evaluated by the pathologist.

Lymph node involvement is a strong predictor of how the cancer may behave and whether it is likely to return or spread after surgery. If cancer is found in the lymph nodes, your doctor may recommend additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation, or immunotherapy, to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Response to prior treatment

If you received chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of both before surgery (called neoadjuvant therapy), your pathology report will often include a description of how the tumor responded to that treatment. This is called the tumor regression score and it helps doctors understand how much of the tumor was destroyed before surgery.

One commonly used system is the modified Ryan scheme, which assigns a score from 0 to 3 based on how many cancer cells are still visible under the microscope after treatment.

Score 0 – Complete response: No cancer cells are seen in the tissue. This means the treatment worked extremely well and destroyed all detectable tumor cells.

Score 1 – Near complete response: Only single cancer cells or small groups of cancer cells are seen. This indicates a very strong response to treatment, with very few cancer cells left.

Score 2 – Partial response: There are still cancer cells present, but the pathologist sees signs that the tumor shrank or was affected by the treatment. This means the treatment helped, but the tumor was not completely destroyed.

Score 3 – Poor or no response: The tumor still looks much like it did before treatment, with many cancer cells and no clear signs that it shrank or was damaged. This means the treatment did not work well against the tumor.

What is the prognosis?

The most important factor that determines prognosis is the stage of the cancer at the time of diagnosis. Other factors include tumor grade, lymphovascular invasion (cancer in blood vessels or lymphatics), perineural invasion (cancer around nerves), and response to treatment. Tumors with HER2 overexpression or PD-L1 positivity may respond to targeted therapies or immunotherapy.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What part of my esophagus is affected by the tumor?

-

Was the cancer limited to the inner layers of the esophagus or did it grow deeper into the wall?

-

Were any lymph nodes involved? If so, how many?

-

Did the cancer show any lymphovascular or perineural invasion?

-

What was the histologic grade of the tumor?

-

Were the surgical margins clear, or were cancer cells seen at the edge of the removed tissue?

-

Did the tumor show signs of response to chemotherapy or radiation (tumor regression)?

-

Was testing for HER2 performed, and if so, what were the results?

-

Was the cancer tested for PD-L1 or mismatch repair proteins and what does that mean for treatment?

-

Based on the pathology report, what is my pathologic stage (pTNM)?

-

What additional treatments might be recommended based on these findings?