by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

July 31, 2025

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare type of cancer that grows slowly but can invade deeply into surrounding tissues. It most commonly starts in the major salivary glands such as the parotid, submandibular, or sublingual glands. However, it can also develop in other parts of the body, including the skin, lungs, breasts, and prostate gland.

Although adenoid cystic carcinoma tends to grow slowly, it can spread widely along nerves and other nearby structures, which can make complete surgical removal difficult. Unlike many other cancers, it usually does not spread to lymph nodes unless it undergoes high grade transformation, a change that makes the tumour behave more aggressively.

What are the symptoms of adenoid cystic carcinoma?

The symptoms of adenoid cystic carcinoma depend on where the tumour is located and how large it is.

-

In the head and neck, symptoms may include pain, numbness, or tingling due to the tumour growing around nerves.

-

In the skin or breast, the tumour may appear as a painless lump or nodule.

-

In the lungs, the tumour may cause coughing, wheezing, or shortness of breath.

Because the tumour grows slowly, some patients may not notice any symptoms until it has become quite large.

What causes adenoid cystic carcinoma?

Doctors do not yet know what causes adenoid cystic carcinoma. Unlike other cancers, it is not strongly linked to lifestyle or environmental factors like smoking or diet. Instead, this type of cancer is associated with specific genetic changes that affect how cells grow and divide.

Common genetic changes:

-

MYB-NFIB fusion: The most common genetic alteration in adenoid cystic carcinoma is a fusion between two genes called MYB and NFIB. This genetic change causes the MYB gene to become overactive, which promotes uncontrolled cell growth.

-

MYBL1 rearrangements: In tumours that do not have the MYB-NFIB fusion, a related gene called MYBL1 may be altered. These changes have similar effects on tumour growth.

These genetic alterations are considered early steps in the development of adenoid cystic carcinoma and help pathologists confirm the diagnosis when testing the tumour.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of adenoid cystic carcinoma is usually made after a sample of the tumour is removed and examined under a microscope by a pathologist.

The tissue sample may be taken by:

-

Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) or core needle biopsy, which removes a small part of the tumour

-

Surgical excision or resection, which removes the entire tumour

The tissue is then processed and studied to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate how the tumour behaves.

What does adenoid cystic carcinoma look like under the microscope?

When examined under the microscope, adenoid cystic carcinoma is made up of two types of tumour cells: ductal cells and myoepithelial cells. For this reason, it is sometimes called a biphasic tumour.

The tumour cells often grow in one of two patterns:

-

Tubular pattern: The cells form small round structures that look like tiny tubes with a hollow centre.

-

Cribriform pattern: The cells form large clusters with many small round spaces called microcysts, which often contain pink or blue material.

These growth patterns are commonly seen in classic adenoid cystic carcinoma and help pathologists make the diagnosis.

What is high grade transformation?

High grade transformation means that the tumour has changed into a more aggressive form that is more likely to spread and recur.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma with high grade transformation often shows the following features when examined under the microscope:

-

The tumour cells lose their normal architecture and begin to grow in solid sheets without the usual tubular or cribriform patterns.

-

The cells often appear more abnormal (called pleomorphic).

-

There may be increased mitotic activity, which means more tumour cells are dividing.

-

Areas of necrosis, or dead tumour tissue, may be seen.

High grade transformation is important because it significantly increases the risk of the tumour spreading to lymph nodes, the lungs, or other parts of the body. Treatment decisions may change if high grade transformation is seen in your pathology report.

Extraparenchymal extension

Extraparenchymal extension means that the tumour has spread outside of the salivary gland into the surrounding tissues, such as fat, muscle, or skin. This finding is only reported for tumours that start in one of the three major salivary glands—the parotid, submandibular, or sublingual glands.

The presence of extraparenchymal extension is important because it suggests that the tumour is more aggressive and may be more difficult to remove completely. Tumours that have grown beyond the salivary gland are given a higher pathologic stage (pT), which helps your medical team estimate the risk of recurrence and decide if additional treatment is needed after surgery.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells have entered small blood vessels or lymphatic vessels near the tumour. Blood vessels carry blood throughout the body, while lymphatic vessels carry a fluid called lymph to the lymph nodes.

This finding is important because these vessels can act like highways, allowing cancer cells to spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body, such as the lungs. If lymphovascular invasion is seen under the microscope, it suggests a higher risk of metastasis and may influence decisions about follow-up care or treatment.

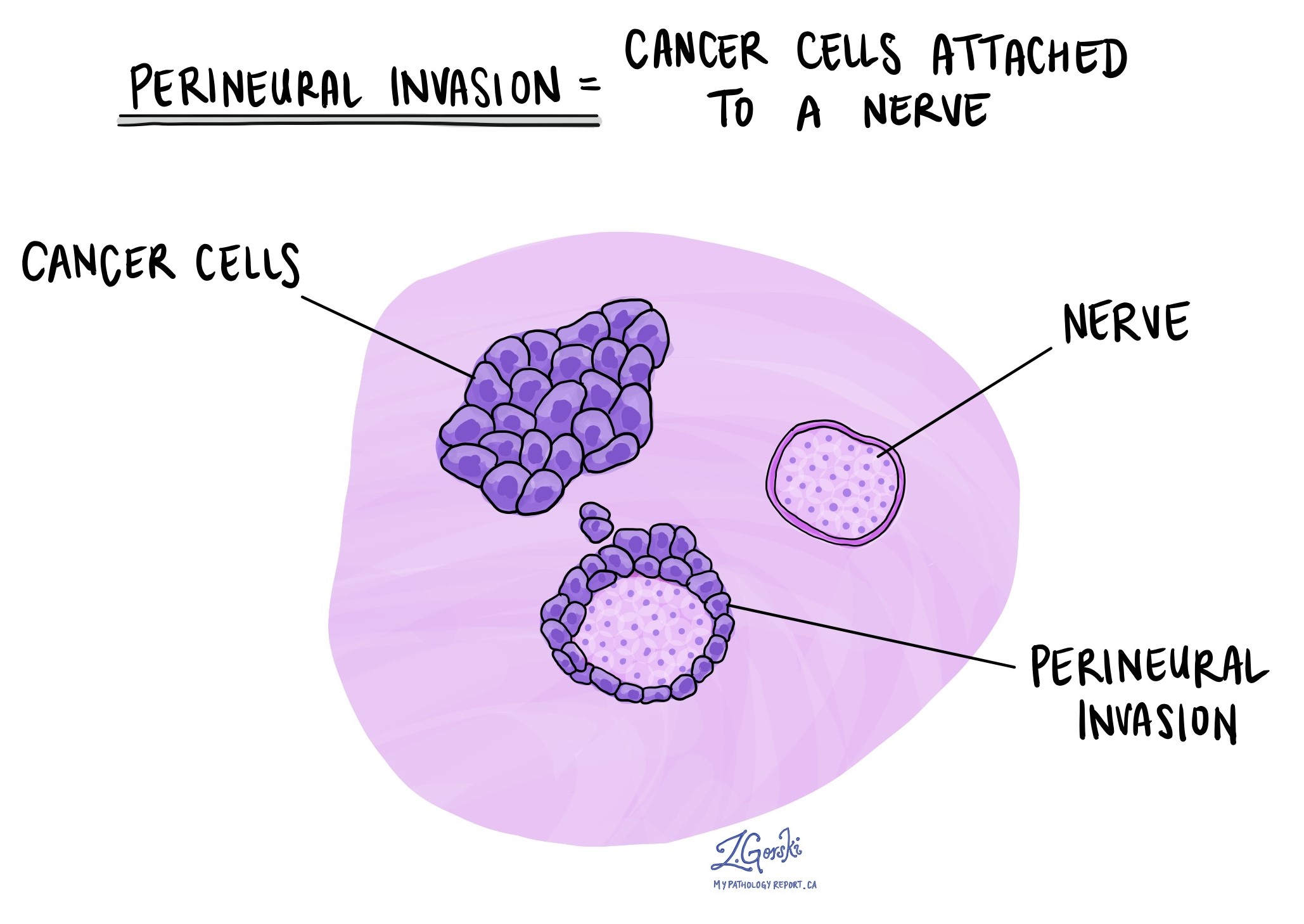

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion means that cancer cells are growing around or along a nerve. This can sometimes cause pain or numbness, depending on which nerve is affected. Perineural invasion is important because it provides another pathway for the tumour to spread into nearby tissues or deeper structures, including bone or muscle.

If perineural invasion is seen in your pathology report, your doctor may recommend additional treatment, such as radiation therapy, to reduce the risk of the cancer coming back.

Margins

A margin is the edge of tissue that is cut during surgery to remove a tumour. After surgery, the pathologist examines the margins under the microscope to see if any cancer cells are present at the edge of the removed tissue.

-

A negative margin means no cancer cells were seen at the edge, suggesting the tumour was completely removed.

-

A positive margin means cancer cells are present at the edge, which raises concern that some tumour may have been left behind.

Your report may also describe the distance between the tumour and the nearest margin, especially if all margins are negative. This information helps your doctors decide whether additional surgery or radiation therapy may be needed.

Margins are only evaluated after the entire tumour has been removed in a procedure such as an excision or resection. They are not typically assessed after a biopsy.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs located throughout the body. Although rare, cancer cells from adenoid cystic carcinoma can spread from the tumour to nearby lymph nodes through tiny lymphatic vessels.

During surgery, lymph nodes near the tumour—especially in the neck region—may be removed and sent to the pathologist to check for cancer cells.

-

A negative lymph node means no cancer cells were found.

-

A positive lymph node means cancer cells were found inside the lymph node.

If cancer is found in a lymph node, your report may also describe the size of the largest group of cancer cells and whether they have spread beyond the outer layer of the node into the surrounding tissue, a feature called extranodal extension.

Examining lymph nodes is important because it helps determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN) and provides information about the risk of recurrence or spread. This helps your medical team decide if additional treatment, such as radiation or chemotherapy, is needed after surgery.

Pathologic stage

Pathologic staging is a system doctors use to describe the size and spread of a tumour. This helps determine how advanced the cancer is and guides treatment decisions. The pathologic stage is usually determined after the tumour is removed and examined by a pathologist, who analyzes the tissue under a microscope. For adenoid cystic carcinoma, staging is based on the “TNM” system, where “T” stands for the size and extent of the primary tumour, “N” refers to lymph node involvement, and “M” indicates whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

Tumour stage (pT)

The tumour stage describes the size of the tumour in the salivary gland and whether it has spread into nearby tissues.

- T0 means there is no evidence of a primary tumour in the salivary gland.

- Tis refers to carcinoma “in situ,” meaning the cancer cells are limited to where they started and have not invaded deeper tissues.

- T1 means the tumour is 2 cm or smaller and has not spread beyond the salivary gland.

- T2 refers to a tumour larger than 2 cm but not larger than 4 cm, still confined to the salivary gland.

- T3 means the tumour is larger than 4 cm or has spread to nearby soft tissues.

- T4 describes more advanced tumours. T4a means the tumour has spread to the skin, jawbone, ear canal, or facial nerve. T4b indicates very advanced cancer that has spread to the base of the skull, nearby bones, or major blood vessels.

Nodal stage (pN)

The nodal stage indicates whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, which are small glands that help the body fight infection. Lymph node involvement can increase the risk of cancer spreading further.

- N0 means there is no spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- N1 indicates the cancer has spread to a single lymph node on the same side of the neck, measuring 3 cm or smaller.

- N2 describes more extensive lymph node involvement:

- N2a: A single lymph node on the same side of the neck is affected, measuring up to 6 cm, or smaller nodes that show signs of cancer outside the node.

- N2b: Multiple lymph nodes on the same side of the neck are affected, none larger than 6 cm.

- N2c: Cancer has spread to lymph nodes on both sides of the neck or on the opposite side, none larger than 6 cm.

- N3 indicates more advanced lymph node involvement. N3a means a node larger than 6 cm is affected. N3b involves multiple nodes or any nodes where cancer has spread outside the lymph node into nearby tissues.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

Has the tumour spread beyond the salivary gland into nearby tissues or nerves?

-

Does the pathology report mention high grade transformation?

-

Were any lymph nodes removed and did they contain cancer?

-

What are the treatment options based on my diagnosis?

-

Will I need additional testing, such as imaging or genetic studies, before deciding on treatment?