by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

April 4, 2024

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is a slow-growing but locally aggressive type of cancer most commonly found in one of the major salivary glands, such as the parotid, submandibular, or sublingual gland. Other locations include the skin, lungs, breasts, and prostate gland. Adenoid cystic carcinoma grows slowly but spreads widely into surrounding tissues. However, unlike other types of cancer, adenoid cystic carcinoma does not typically spread to lymph nodes unless it undergoes high grade transformation.

What are the symptoms of adenoid cystic carcinoma?

The symptoms of adenoid cystic carcinoma depend on where the tumour starts and its size. Symptoms associated with tumours in the head and neck include pain, numbness, and tingling in the area of the tumour. In the skin or breast, the tumour may appear as a painless lump or nodule. Tumours in the lungs may cause shortness of breath, coughing, or wheezing.

What causes adenoid cystic carcinoma?

The precise cause of adenoid cystic carcinoma is not fully understood. Unlike some other types of cancer, there are no clear lifestyle or environmental risk factors directly linked to its development. Instead, the emergence of this cancer type is primarily attributed to genetic mutations and chromosomal rearrangements that affect cell growth and differentiation.

- Genetic mutations and chromosomal rearrangements: The hallmark of adenoid cystic carcinoma is the presence of specific genetic changes, including the MYB-NFIB gene fusion, resulting from a translocation between chromosomes 6 and 9. This fusion gene leads to the overexpression of the MYB gene, which is involved in regulating cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis. Such genetic alterations disrupt normal cellular functions, leading to uncontrolled cell growth and the formation of tumours.

- MYBL1 rearrangements: In cases where the MYB-NFIB fusion is absent, rearrangements involving the MYBL1 gene, a close relative of MYB, have been observed. These alterations contribute to the cancer’s development by similar mechanisms, promoting abnormal cell proliferation.

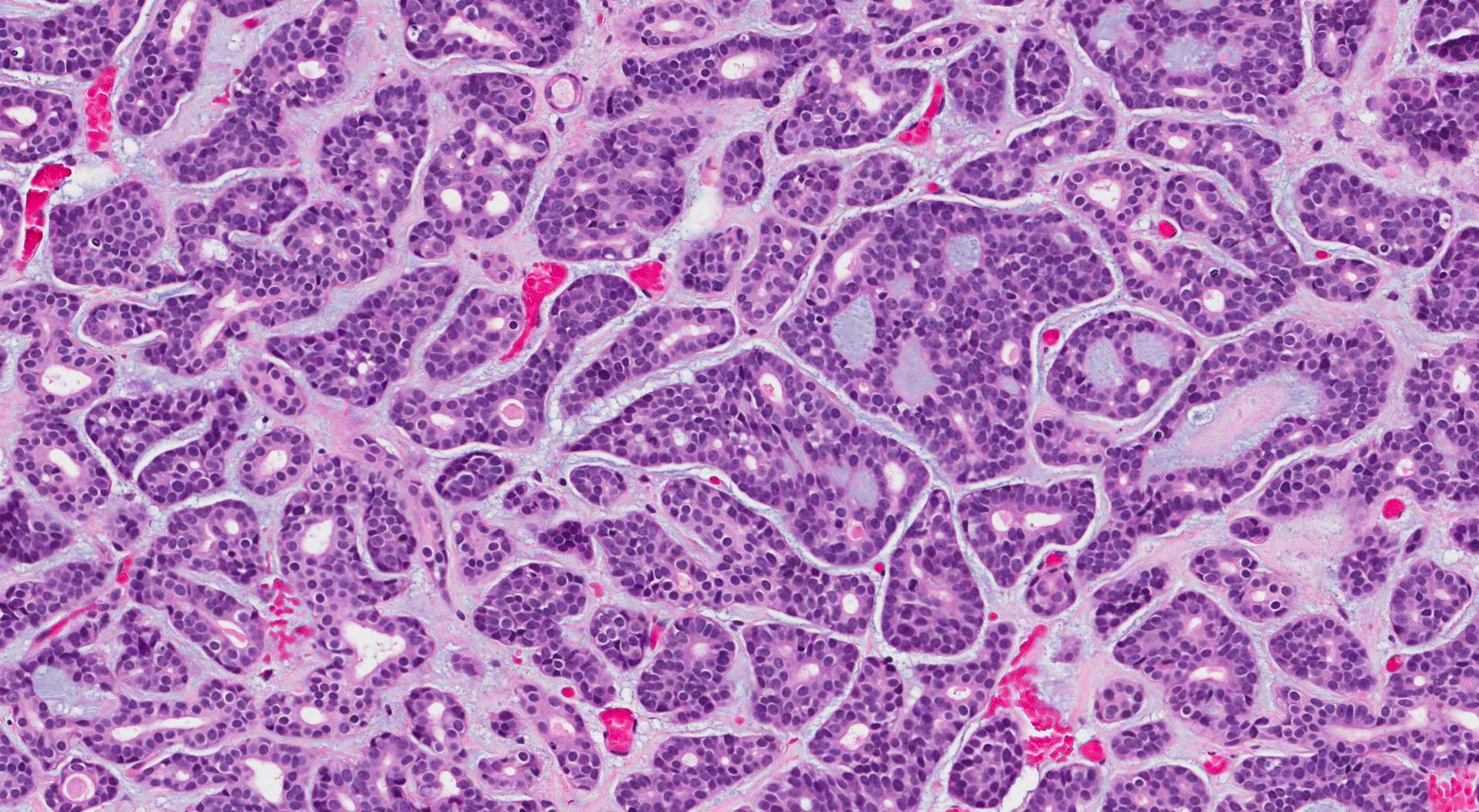

Microscopic features of this tumour

When examined under the microscope, adenoid cystic carcinoma is made up of two types of cells: ductal cells and myoepithelial cells. As a result, it is sometimes described as a biphasic salivary gland tumour. The tumour cells in adenoid cystic carcinoma commonly show two growth patterns: tubular and cribriform. In the tubular pattern, the tumour cells connect to create a ring-shaped structure with a hole in the centre. In the cribriform pattern, the tumour cells connect to form makes small spaces called microcysts. These microcysts are often filled with blue or pink-coloured material.

High grade transformation

High grade transformation in adenoid cystic carcinoma means that the tumour has started to change in a way that results in more aggressive behaviour. When examined under the microscope, tumours with high grade transformation have lost some of the features seen in a typical tumour. In particular, the tumour cells often stick together to create large groups of cells without the microcysts typically seen in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Pathologists use the term solid to describe this pattern of growth. Tumours with high grade transformation often have more mitotic figures (tumour cells dividing to create new tumour cells) and a type of cell death called necrosis may also be seen. High grade transformation is important because these tumours are more likely to metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes and the lungs.

Extraparenchymal extension

In the context of a salivary gland tumour such as adenoid cystic carcinoma, extraparenchymal extension (EPE) is the spread of the tumour beyond the salivary gland into the surrounding tissues. This condition is often associated with a more aggressive form of cancer, indicating that the tumour can invade beyond its original site. The presence of extraparenchymal extension is associated with more aggressive tumours and a worse prognosis.

Extraparenchyma, extension impacts the pathologic stage but only for tumours arising from one of the major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual). Tumours with extraparenchymal extension are generally classified at a higher stage, reflecting their advanced nature and the associated challenges in treatment and management.

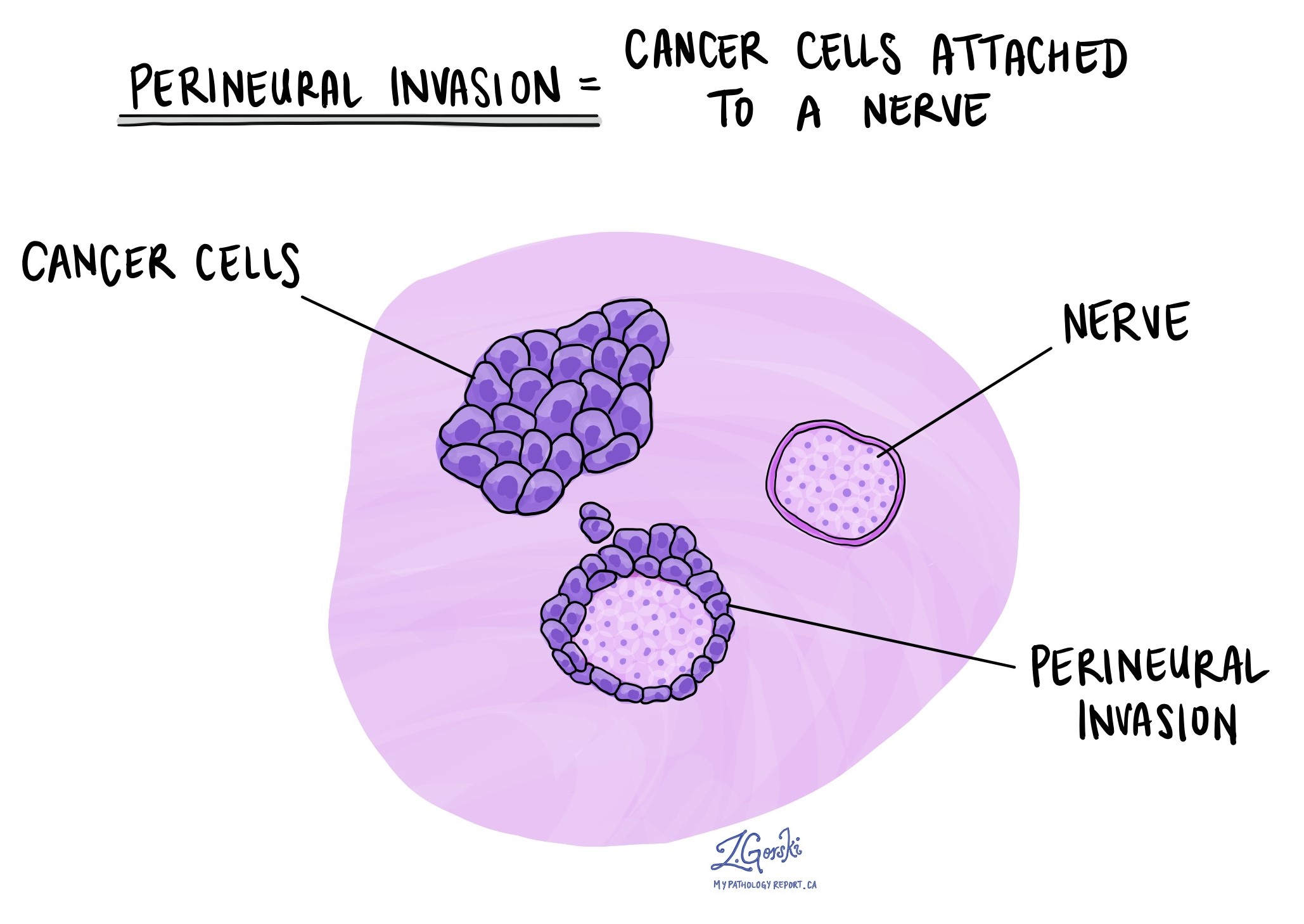

Perineural invasion

Pathologists use the term perineural invasion (PNI) to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that specifically refers to cancer cells found inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. The presence of perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery. Perineural invasion is almost always seen in adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels, thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, contrast with lymphatic vessels, which carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic vessels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes, scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it enables cancer cells to spread to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the liver, via the blood or lymphatic vessels. Lymphovascular invasion is typically only seen in adenoid cystic carcinomas that have undergone high grade transformation.

Margins

In pathology, a margin refers to the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure like an excision or resection, aimed at removing the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are present at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was fully removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs located throughout the body. Cancer cells can travel from a tumour to these lymph nodes via tiny lymphatic vessels. For this reason, doctors often remove and microscopically examine lymph nodes to look for cancer cells. This process, where cancer cells move from the original tumour to another body part, like a lymph node, is termed metastasis.

Cancer cells usually first migrate to lymph nodes near the tumour, although distant lymph nodes may also be affected. Consequently, surgeons typically remove lymph nodes closest to the tumour first. They might remove lymph nodes farther from the tumour if they are enlarged and there’s a strong suspicion they contain cancer cells.

Pathologists will examine any lymph nodes removed under a microscope, and the findings will be detailed in your report. A “positive” result indicates the presence of cancer cells in the lymph node, while a “negative” result means no cancer cells were found. If the report finds cancer cells in a lymph node, it might also specify the size of the largest cluster of these cells, often referred to as a “focus” or “deposit.” Extranodal extension occurs when tumour cells penetrate the lymph node’s outer capsule and spread into the adjacent tissue.

Examining lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, it helps determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, discovering cancer cells in a lymph node suggests an increased risk of finding cancer cells in other body parts later. This information guides your doctor in deciding whether you need additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy.

Pathologic stage

Pathologic staging is a system doctors use to describe the size and spread of a tumour. This helps determine how advanced the cancer is and guides treatment decisions. The pathologic stage is usually determined after the tumour is removed and examined by a pathologist, who analyzes the tissue under a microscope. For adenoid cystic carcinoma, staging is based on the “TNM” system, where “T” stands for the size and extent of the primary tumour, “N” refers to lymph node involvement, and “M” indicates whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

Tumour stage (pT)

The tumour stage describes the size of the tumour in the salivary gland and whether it has spread into nearby tissues.

- T0 means there is no evidence of a primary tumour in the salivary gland.

- Tis refers to carcinoma “in situ,” meaning the cancer cells are limited to where they started and have not invaded deeper tissues.

- T1 means the tumour is 2 cm or smaller and has not spread beyond the salivary gland.

- T2 refers to a tumour larger than 2 cm but not larger than 4 cm, still confined to the salivary gland.

- T3 means the tumour is larger than 4 cm or has spread to nearby soft tissues.

- T4 describes more advanced tumours. T4a means the tumour has spread to the skin, jawbone, ear canal, or facial nerve. T4b indicates very advanced cancer that has spread to the base of the skull, nearby bones, or major blood vessels.

Nodal stage (pN)

The nodal stage indicates whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, which are small glands that help the body fight infection. Lymph node involvement can increase the risk of cancer spreading further.

- N0 means there is no spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- N1 indicates the cancer has spread to a single lymph node on the same side of the neck, measuring 3 cm or smaller.

- N2 describes more extensive lymph node involvement:

- N2a: A single lymph node on the same side of the neck is affected, measuring up to 6 cm, or smaller nodes that show signs of cancer outside the node.

- N2b: Multiple lymph nodes on the same side of the neck are affected, none larger than 6 cm.

- N2c: Cancer has spread to lymph nodes on both sides of the neck or on the opposite side, none larger than 6 cm.

- N3 indicates more advanced lymph node involvement. N3a means a node larger than 6 cm is affected. N3b involves multiple nodes or any nodes where cancer has spread outside the lymph node into nearby tissues.

What is the prognosis for a patient diagnosed with adenoid cystic carcinoma?

The prognosis for an individual diagnosed with adenoid cystic carcinoma can vary widely and is influenced by several factors. This type of cancer is known for its slow growth, but it also tends to recur and metastasize, even many years after initial treatment, which complicates the prognosis.

Factors that influence prognosis:

- Tumour location: The site of the primary tumour can impact the prognosis. Tumours in places that are difficult to remove surgically altogether, or those in areas with a high risk of functional impairment post-surgery, may have a poorer prognosis.

- Tumour size and stage: Larger tumours and those that are more advanced at the time of diagnosis (having spread to lymph nodes or distant sites) tend to have a worse prognosis. Early-stage cancers confined to the site of origin usually have a better outcome.

- High grade transformation: High grade transformation means the tumour has become a more aggressive form of cancer. Tumours with high grade transformation are more likely to spread to lymph nodes and are associated with worse prognosis.

- Perineural invasion: Adenoid cystic carcinoma often invades nerves, which is known as perineural invasion. This characteristic can lead to a higher risk of local recurrence and is associated with a poorer prognosis.

- Metastasis: The presence of metastases, especially in distant organs like the lungs, negatively impacts survival rates.

- Surgical margins: Clear surgical margins (no cancer cells found at the edge of the removed tissue) are associated with a better prognosis. Positive margins indicate a higher risk of recurrence.

- Patient age and overall health: Younger patients and those in good overall health may have a better prognosis, partly due to a better capacity to undergo aggressive treatments and recover from them.

About this article

Doctors wrote this article to help you read and understand your pathology report. Contact us if you have questions about this article or your pathology report. For a complete introduction to your pathology report, read this article.