by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

August 22, 2024

Background:

Ampullary adenocarcinoma is a type of cancer that forms in the ampulla of Vater. The ampulla of Vater is a small area where the bile duct and pancreatic duct join and empty into the small intestine. This type of cancer is rare but can be aggressive.

What are the symptoms of ampullary adenocarcinoma?

Symptoms of ampullary adenocarcinoma can include:

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), which occurs when the tumour blocks the bile duct.

- Abdominal pain, especially in the upper right side of the abdomen.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Pale stools and dark urine are signs of bile duct obstruction.

What causes ampullary adenocarcinoma?

The exact cause of ampullary adenocarcinoma is not always known. However, risk factors include chronic inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis), certain genetic conditions, and exposure to harmful substances like tobacco smoke.

What genetic changes are associated with ampullary adenocarcinoma?

Specific genetic mutations are linked to ampullary adenocarcinoma. These include changes in the KRAS and TP53 genes, which control cell growth and division. These mutations can lead to uncontrolled cell growth, a hallmark of cancer.

How is the diagnosis of ampullary adenocarcinoma made?

The diagnosis is typically made through a combination of imaging studies (like CT or MRI scans), endoscopic procedures, and a biopsy, where a pathologist examines a small tissue sample under a microscope.

Histologic subtypes of ampullary adenocarcinoma

Ampullary adenocarcinoma can be classified into subtypes based on how the cells look under the microscope. These subtypes can help predict the tumour’s behaviour.

Histologic subtypes of ampullary adenocarcinoma include:

- Intestinal subtype: This is the most common subtype of ampullary adenocarcinoma. The tumour cells resemble the cells normally found in the small intestine. This subtype tends to have a better prognosis.

- Pancreatobiliary subtype: This is the second most common type of ampullary adenocarcinoma. The tumour cells resemble those normally found in the pancreas or bile ducts. This subtype is more aggressive than the intestinal subtype.

- Mucinous subtype: This subtype of ampullary adenocarcinoma is made up of tumour cells that contain intracellular mucin. Tumours with mucinous features may behave aggressively but can vary widely.

- Poorly cohesive subtype: The tumour cells in poorly cohesive type ampullary adenocarcinoma do not form glands and tend to spread widely into surrounding tissues. Large round signet ring cells are often found in this subtype. Poorly cohesive tumours are also more likely to spread to lymph nodes.

- Medullary subtype: This rare subtype has large cells with a pushing border. Medullary tumours may be associated with specific genetic syndromes, although their behaviour can be highly variable.

- Adenosquamous subtype: The adenosquamous subtype of ampullary adenocarcinoma contains both glandular and squamous cells. These tumours are often aggressive.

- Undifferentiated subtype: The tumour cells in undifferentiated ampullary adenocarcinoma do not look like normal cells. Large anaplastic cells and osteoclast-like giant cells may also be seen. This subtype tends to be very aggressive.

Histologic grade

Ampullary adenocarcinoma is divided into three grades – well differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated. The grade is based on the percentage of the tumour cells forming round structures called glands. A tumour that does not create any glands is called undifferentiated. The grade is important because poorly differentiated and undifferentiated tumours tend to behave more aggressively. For example, these tumours are more likely to spread to lymph nodes and other body parts.

- Well differentiated: More than 95% of the tumour comprises glands. Pathologists also describe these tumours as grade 1.

- Moderately differentiated: 50 to 95% of the tumour comprises glands. Pathologists also describe these tumours as grade 2.

- Poorly differentiated: Less than 50% of the tumour comprises glands. Pathologists also describe these tumours as grade 3.

- Undifferentiated: Very few glands are seen anywhere in the tumour.

Tumour invasion

Ampullary adenocarcinoma starts in the ampulla of Vater, but tumour cells can spread into nearby tissues and organs as the tumour gets bigger. Pathologists describe this as invasion, which is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT). Tumour invasion into surrounding organs and tissues will usually only be described in your report after removing the entire tumour.

Limited to the ampulla

The ampulla of Vater is where the bile duct and pancreatic duct meet and empty into the duodenum. When the tumour is confined to the ampulla, it has not yet invaded surrounding structures. Tumours limited to the ampulla are usually detected earlier and have a better prognosis because they have not spread beyond this small anatomical area.

Invades beyond the sphincter of Oddi

The sphincter of Oddi is a ring of muscle that surrounds the end of the bile duct and pancreatic duct, controlling the flow of bile and pancreatic enzymes into the duodenum. When a tumour invades beyond this sphincter, it spreads into nearby tissues. Invasion beyond the sphincter of Oddi indicates a more advanced tumour that has begun to infiltrate local structures, but the invasion is still relatively confined.

Invades duodenal submucosa

The submucosa is a layer of tissue just beneath the inner lining (mucosa) of the duodenum. This layer contains blood vessels, nerves, and connective tissue. Tumours invading the submucosa have breached the first layer of the duodenum but have not yet reached deeper layers, indicating intermediate progression.

Invades duodenal muscularis propria

The muscularis propria is the thick layer of muscle in the wall of the duodenum that helps move food through the digestive tract. Invasion into this muscular layer indicates more aggressive tumour behaviour and increases the risk of further spread to nearby organs.

Invades into the pancreas

The pancreas is located near the duodenum and produces digestive enzymes and insulin. The ampulla of Vater is very close to the head of the pancreas. Invasion into the pancreas indicates significant tumour spread. This stage can impact pancreatic function and is associated with a worse prognosis due to the complexity of treatment.

Invades into peripancreatic soft tissue

The peripancreatic soft tissue includes the fatty and connective tissue surrounding the pancreas. When the tumour invades this tissue, it typically signifies a more advanced stage. This invasion can complicate surgical removal, indicating a higher likelihood of metastatic spread.

Invades duodenal serosa

The serosa is the outermost layer of the duodenum, covering the outside of the organ. Tumour invasion into the serosa indicates that the cancer has reached the outermost boundary of the duodenum and is likely to spread to adjacent structures, representing a more advanced stage.

Invades adjacent organs such as the stomach, gallbladder, and major arteries

- Stomach: Located just above the duodenum, the stomach may be involved if the tumour extends beyond the duodenum.

- Gallbladder: Located close to the liver and bile ducts, the gallbladder may be invaded if the tumour spreads from the bile duct area.

- Major arteries: These include the superior mesenteric artery and celiac artery, which supply blood to the stomach, pancreas, and intestines.

Invasion of these adjacent organs and major blood vessels indicates a very advanced tumour stage with a poor prognosis. It may limit surgical options and significantly affect treatment decisions.

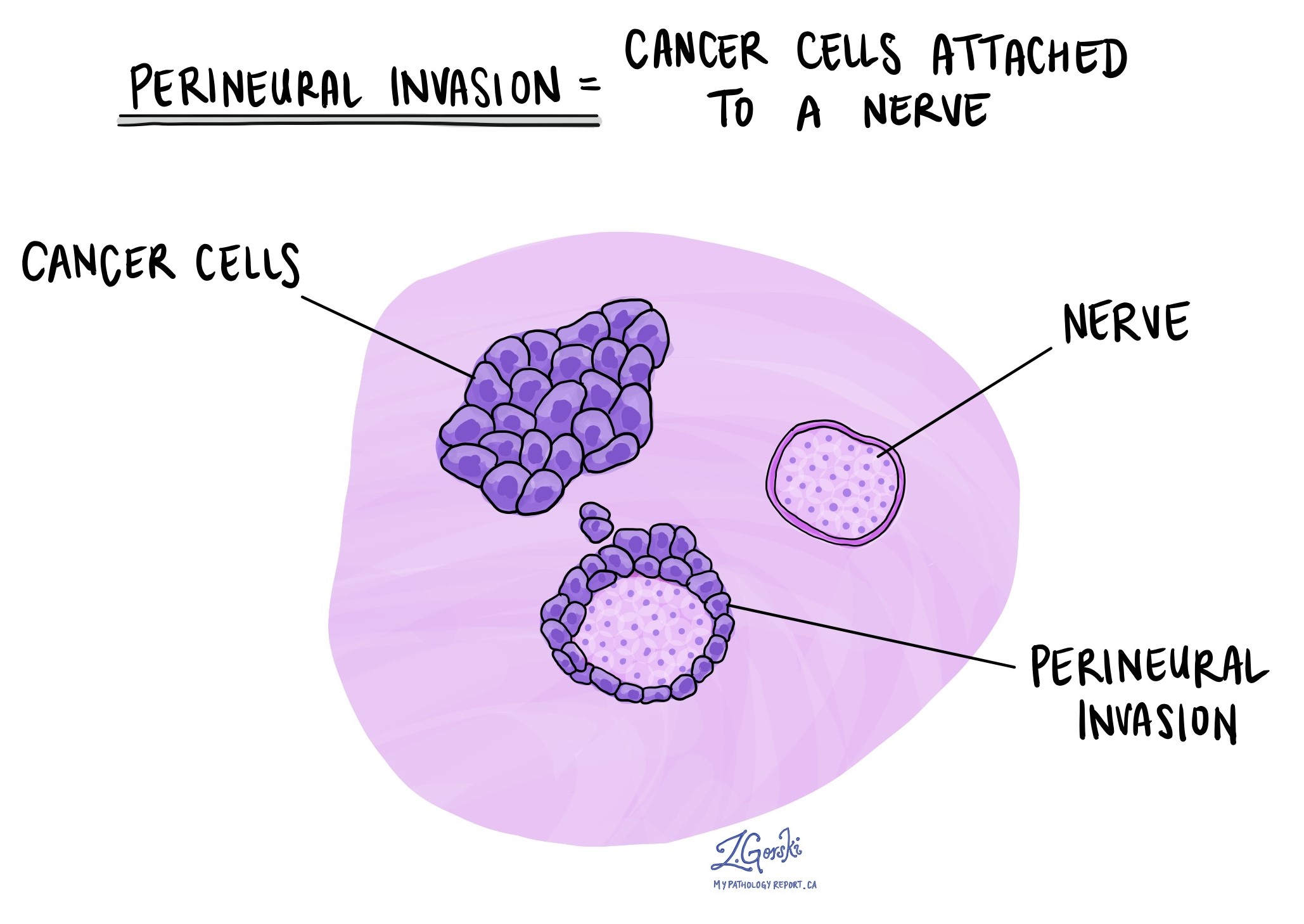

Perineural invasion

Pathologists use the term “perineural invasion” to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that refers explicitly to cancer cells found inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. Perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, unlike lymphatic vessels, which carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic vessels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it enables cancer cells to spread to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the liver, via the blood or lymphatic vessels.

Lymph nodes

Small immune organs, known as lymph nodes, are located throughout the body. Cancer cells can travel from a tumour to these lymph nodes via tiny lymphatic vessels. For this reason, doctors often remove and microscopically examine lymph nodes to look for cancer cells. This process, where cancer cells move from the original tumour to another body part, like a lymph node, is termed metastasis.

Cancer cells usually first migrate to lymph nodes near the tumour, although distant lymph nodes may also be affected. Consequently, surgeons typically remove lymph nodes closest to the tumour first. They might remove lymph nodes farther from the tumour if they are enlarged and there’s a strong suspicion they contain cancer cells.

Pathologists will examine any lymph nodes removed under a microscope; the findings will be detailed in your report. A “positive” result indicates the presence of cancer cells in the lymph node, while a “negative” result means no cancer cells were found. If the report finds cancer cells in a lymph node, it might also specify the size of the largest cluster of these cells, often referred to as a “focus” or “deposit.”

Examining lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, it helps determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, discovering cancer cells in a lymph node suggests an increased risk of later finding cancer cells in other body parts. This information guides your doctor in deciding whether you need additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure like an excision or resection, which removes the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was entirely removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

Pathologic tumour stage (pT) for ampullary adenocarcinoma

The pathologic tumour stage (pT) describes how large the tumour is and whether it has grown into nearby structures.

- pT0: No evidence of primary tumour.

- pTis: Carcinoma in situ.

- pT1: Tumour limited to the ampulla of Vater or sphincter of Oddi or invades beyond the sphincter of Oddi into the duodenal submucosa.

- pT2: Tumour invades into the muscularis propria of the duodenum.

- pT3: Tumour directly invades the pancreas (up to 0.5 cm) or extends more than 0.5 cm into the pancreas, or extends into peripancreatic or periduodenal tissue or duodenal serosa without involvement of major arteries.

- pT4: Tumour involves major arteries like the celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery, and common hepatic artery.

Pathologic nodal stage (pN) for ampullary adenocarcinoma

The pathologic nodal (N) stage describes whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes.

- pN0: No regional lymph node metastasis.

- pN1: Metastasis to one to three regional lymph nodes.

- pN2: Metastasis to four or more regional lymph nodes.

About this article

Doctors wrote this article to help you read and understand your pathology report. Contact us if you have questions about this article or your pathology report. For a complete introduction to your pathology report, read this article.