by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

October 3, 2025

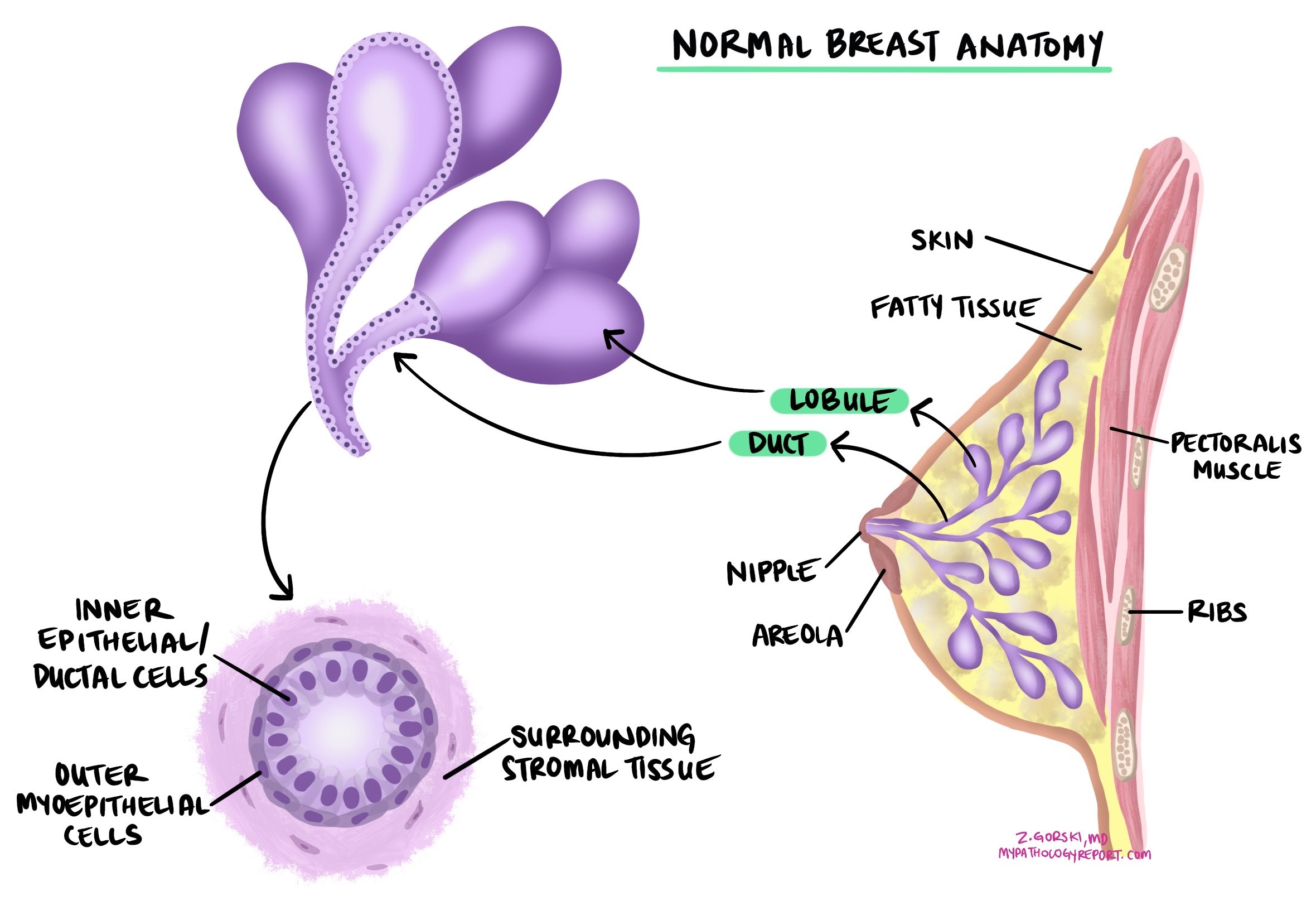

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a noninvasive type of breast cancer that starts in the lining of the breast ducts (the tubes that carry milk). Noninvasive means that all the cancer cells are confined to the ducts and glands. They have not broken through the duct wall into nearby breast tissue. Because the cells are contained, DCIS cannot spread to lymph nodes or other organs unless it first becomes invasive. Treatment aims to keep it from becoming invasive.

What are the symptoms of ductal carcinoma in situ?

Most people with DCIS have no symptoms. DCIS is usually found on a screening mammogram, often as tiny calcium deposits (microcalcifications). Less commonly, someone may notice a lump, nipple discharge (which can be bloody), or subtle changes in breast shape or texture.

What causes DCIS?

DCIS develops when breast duct cells acquire DNA changes that let them grow and divide too quickly. Risk is influenced by many of the same factors as invasive breast cancer, including inherited variants (such as BRCA1/BRCA2), family history, long lifetime exposure to estrogen (for example, later menopause or hormone therapy), higher breast density, obesity, alcohol use, and prior chest radiation.

What is the risk of developing invasive breast cancer after a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ?

DCIS is confined to the ducts, but some cases can progress to invasive ductal carcinoma if not treated. After treatment, cancer can recur in the same breast as DCIS again or, less commonly, as an invasive cancer. Risk depends on several features in the pathology report (for example, nuclear grade, presence of necrosis, margin status, and size/extent), as well as treatment choices (such as surgery type, radiation, and endocrine therapy when appropriate). The risk to the opposite breast is increased only slightly compared with the same breast.

What stage is ductal carcinoma in situ?

Because the cells are confined to ducts and glands, DCIS is always staged as pTis (carcinoma in situ).

How is the diagnosis made?

DCIS is usually diagnosed on core needle biopsy performed for an abnormal mammogram. A pathologist confirms DCIS when all abnormal cells are inside ducts and glands. If any cancer cells are found outside a duct (in surrounding tissue), the diagnosis changes to invasive ductal carcinoma. After diagnosis, surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy) removes the remaining disease and allows complete evaluation, including margins.

Nuclear grade

Nuclear grade describes how abnormal the cell nuclei (the cell’s control center) look and how actively the cells are dividing. It helps estimate the chance of recurrence or progression.

-

Low nuclear grade (grade 1): Cells have small, uniform nuclei and look closer to normal. Mitotic figures (cells visibly dividing under the microscope) are rare. Low-grade DCIS is less likely to recur or progress if completely treated.

-

Intermediate nuclear grade (grade 2): Cells show moderate enlargement and variation. Mitotic activity is present but limited. Risk sits between low and high grade.

-

High nuclear grade (grade 3): Cells have large, irregular nuclei (pleomorphic) and frequent mitoses. High grade is more often associated with comedonecrosis (dead cells in the duct center) and carries a higher risk of recurrence or progression to invasive cancer without appropriate treatment.

Your report may also note mitotic rate explicitly. A higher mitotic rate means more cells are dividing, which generally correlates with a higher risk of recurrence.

Histologic subtypes of ductal carcinoma in situ

DCIS is also described by the pattern the cells make inside ducts. These patterns help radiology-pathology correlation and sometimes relate to risk, but treatment decisions are guided by the whole report (grade, size/extent, necrosis, margins), not the pattern alone.

-

Solid pattern: Cancer cells fill the duct from wall to wall with no spaces. On imaging it may form linear or segmental calcifications. Solid DCIS is common in high-grade disease but can occur at any grade.

-

Cribriform pattern: Cells form evenly spaced round holes (“Swiss-cheese” look) within the duct. This pattern is often low or intermediate grade and may be associated with granular or amorphous calcifications.

-

Micropapillary pattern: Tiny finger-like tufts project into the duct without a blood-vessel core. Micropapillary DCIS can be extensive and is sometimes linked with a higher local recurrence risk, particularly when high grade or large in extent.

-

Papillary pattern: Branching fronds protrude into the duct with delicate blood-vessel cores. Pathologists distinguish this from benign intraductal papilloma using the cell features and special stains. Papillary DCIS may form a mass but is still in situ if the duct wall is intact.

What does comedonecrosis mean?

Comedonecrosis is a term pathologists use when dead cancer cells are seen in the center of a duct affected by DCIS. Under the microscope, this appears as a plug of debris made up of dead tumor cells, sometimes with calcium deposits.

Comedonecrosis is important because it is most often seen in high-grade DCIS, which is more likely to come back after treatment and to progress to invasive ductal carcinoma if untreated. For this reason, when comedonecrosis is reported in a pathology report, it usually indicates a more aggressive form of DCIS that requires careful management.

How do pathologists determine the size of ductal carcinoma in situ?

The size (extent) of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) describes how much of the breast is involved by the abnormal cells. Although size does not change the official stage (all DCIS is stage pTis), it is still very important for patient care. The extent of DCIS helps doctors estimate the risk of recurrence, the likelihood of finding invasive cancer nearby, and whether breast-conserving surgery is possible.

Why is size hard to measure in ductal carcinoma in situ?

Unlike invasive cancers, which usually form a solid mass, DCIS grows inside the milk ducts. The duct system is a branching network, and the abnormal cells may be scattered across a large area. This makes it difficult to measure the true size. Other factors that make measurement challenging include:

-

DCIS often spreads in a branching 3-D pattern that is hard to see on a single microscope slide.

-

Breast tissue is soft and compressible, so the size may appear different during surgery, specimen imaging, or lab processing.

-

DCIS may not be removed in one piece, especially if it involves a large area.

-

Imaging (such as mammography) may show calcifications linked to DCIS, but these sometimes underestimate or overestimate the true size.

How do pathologists estimate the size?

Pathologists use several methods to estimate how much breast tissue is affected:

-

Single slide measurement – If DCIS is confined to one piece of tissue, the size can be measured directly. This works best for small lesions.

-

Serial sequential sampling – The entire specimen is carefully mapped and sliced, and the extent is reconstructed from all the pieces. This method gives a more accurate picture when DCIS is widespread.

-

Block counting – When DCIS is seen in multiple tissue blocks, the number of involved blocks is multiplied by the thickness of each block to estimate the total size.

-

Margins – If DCIS is close to or touches two opposite edges of the specimen, the distance between those edges can give a minimum estimate of the extent.

-

Visible lesions – Rarely, especially with high-grade DCIS, there may be a visible abnormal area that can be measured. Pathologists still confirm this measurement under the microscope.

In practice, pathologists usually report the largest estimate of size obtained from these methods.

Why is the size important for treatment?

-

Small areas (up to 20 mm) – Breast-conserving surgery with clear margins is often possible.

-

Intermediate areas (20–40 mm) – It may be harder to achieve wide clear margins, so additional surgery could be required.

-

Large areas (>40 mm) – Breast-conserving surgery may not be possible, and mastectomy may be recommended. Larger size also increases the chance that invasive cancer is present somewhere in the tissue.

Even though exact measurement is often difficult, estimating the extent of DCIS provides important information for surgery planning and long-term follow-up.

Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR)

Hormone receptors are proteins found in some breast cancer cells. The two main types tested are estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR). Cancer cells with these receptors utilize hormones such as estrogen and progesterone to promote growth and division. Testing for ER and PR helps guide treatment and predict prognosis.

If testing for ER and PR is performed, your pathology report may include:

-

Percentage of positive cells: For example, “80% ER-positive” means 80% of cancer cells have estrogen receptors.

-

Intensity of staining: Reported as weak, moderate, or strong, this indicates the number of receptors present in the cancer cells.

-

Overall score (Allred or H-score): This combines percentage and intensity, with higher scores indicating a better response to hormone therapy.

Cancer cells are described as hormone receptor-positive if ER or PR is present in at least 1% of cells. These cancers often grow more slowly, are less aggressive, and typically respond well to hormone-blocking therapies, such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors (e.g., anastrozole, letrozole, or exemestane). Hormone therapy helps reduce the chance of cancer recurrence.

Tumours with ER positivity between 1% and 10% are considered ER low positive. These cancers still usually respond better to hormone therapy compared to ER-negative cancers.

Margins

A margin is the edge of tissue removed at surgery.

-

Negative (clear) margin: No DCIS at the cut edge, suggesting complete removal.

-

Positive margin: DCIS reaches the edge, raising the chance of local recurrence.

When margins are close or positive, your team may recommend additional surgery and/or radiation after lumpectomy.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

Is my DCIS low, intermediate, or high nuclear grade?

-

What histologic pattern(s) were reported, and how extensive is the DCIS?

-

Were the surgical margins clear? If not, what are my options?

-

Is my DCIS ER/PR-positive, and would endocrine therapy help reduce recurrence risk?

-

What is my risk of invasive cancer after this diagnosis, and how does treatment change that risk?

-

What follow-up schedule (imaging and visits) do you recommend?