by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD

November 28, 2025

Adenocarcinoma of the colon is the most common type of colon cancer. It starts in the gland-forming cells that line the inner surface of the colon. These cells normally produce mucus, which helps stool move through the large intestine. When these cells become abnormal and grow uncontrolled, they form a tumour called adenocarcinoma.

What causes adenocarcinoma of the colon?

Most colon adenocarcinomas develop slowly over time because of changes in the DNA of the cells that line the colon. These DNA changes can occur randomly, be influenced by lifestyle, or be inherited. In many cases, the tumour begins as a non-cancerous growth called an adenoma or polyp and then progresses to cancer.

Important risk factors include a personal or family history of colorectal polyps or cancer, inherited conditions such as Lynch syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and long-standing inflammation in the colon from conditions like ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. Diets high in red or processed meat and low in fiber, limited physical activity, smoking, and heavy alcohol use also increase risk.

What are the symptoms?

Colon adenocarcinoma often causes no symptoms in its early stages. As the tumour grows, symptoms can include a change in bowel habits such as constipation, diarrhea, or a change in stool shape; rectal bleeding or blood mixed with stool; abdominal discomfort, bloating, or pain; unexplained weight loss; and fatigue or weakness due to anemia, which is a low red blood cell count. Symptoms depend on the tumour’s size and location. Any persistent change in bowel habits or signs of bleeding should be discussed with your doctor.

How is the diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of colon adenocarcinoma is made after a biopsy is examined by a pathologist, a doctor who diagnoses disease by studying tissue under a microscope. The evaluation typically involves a series of steps that identify an abnormal area, confirm cancer under the microscope, and determine the extent of disease.

Clinical evaluation and preparation

Your doctor reviews your symptoms, medical and family history, and risk factors such as prior polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, smoking, diet, and alcohol use. You will receive instructions for bowel preparation so the colon is clean for examination.

Colonoscopy and biopsy

A colonoscopy is performed to examine the entire colon and rectum. During this procedure, the doctor inserts a thin, flexible camera (a colonoscope) through the rectum to examine the colon lining directly. If an abnormal area is seen—such as a polyp, an ulcerated mass, or irregular mucosa—the doctor removes tissue samples (biopsies). If a polyp appears cancerous, it may be entirely removed during the procedure, provided it is safe to do so. Biopsies are preserved and sent to the pathology laboratory for examination.

Microscopic examination

A pathologist examines the biopsy under a microscope. Cancer is diagnosed when the normal glandular structures are replaced by malignant glands or poorly cohesive cancer cells that invade deeper tissue layers. The tumour cells usually have enlarged, irregular nuclei and may produce mucin, which is a type of mucus, although not in the large amounts seen in mucinous adenocarcinoma.

The report describes how the tumour looks (the histologic type), how closely it resembles normal cells (the tumour grade), and whether it shows aggressive features such as lymphatic invasion (cancer cells inside lymphatic channels), vascular invasion (cancer cells inside blood vessels), and perineural invasion (cancer cells growing along nerves).

Imaging and staging studies

If cancer is diagnosed, imaging studies such as CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis help determine whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes or distant organs. Additional tests may include MRI or PET-CT in selected situations. Surgery may then be planned to remove the tumour along with nearby lymph nodes, both to treat the cancer and to provide accurate pathologic staging.

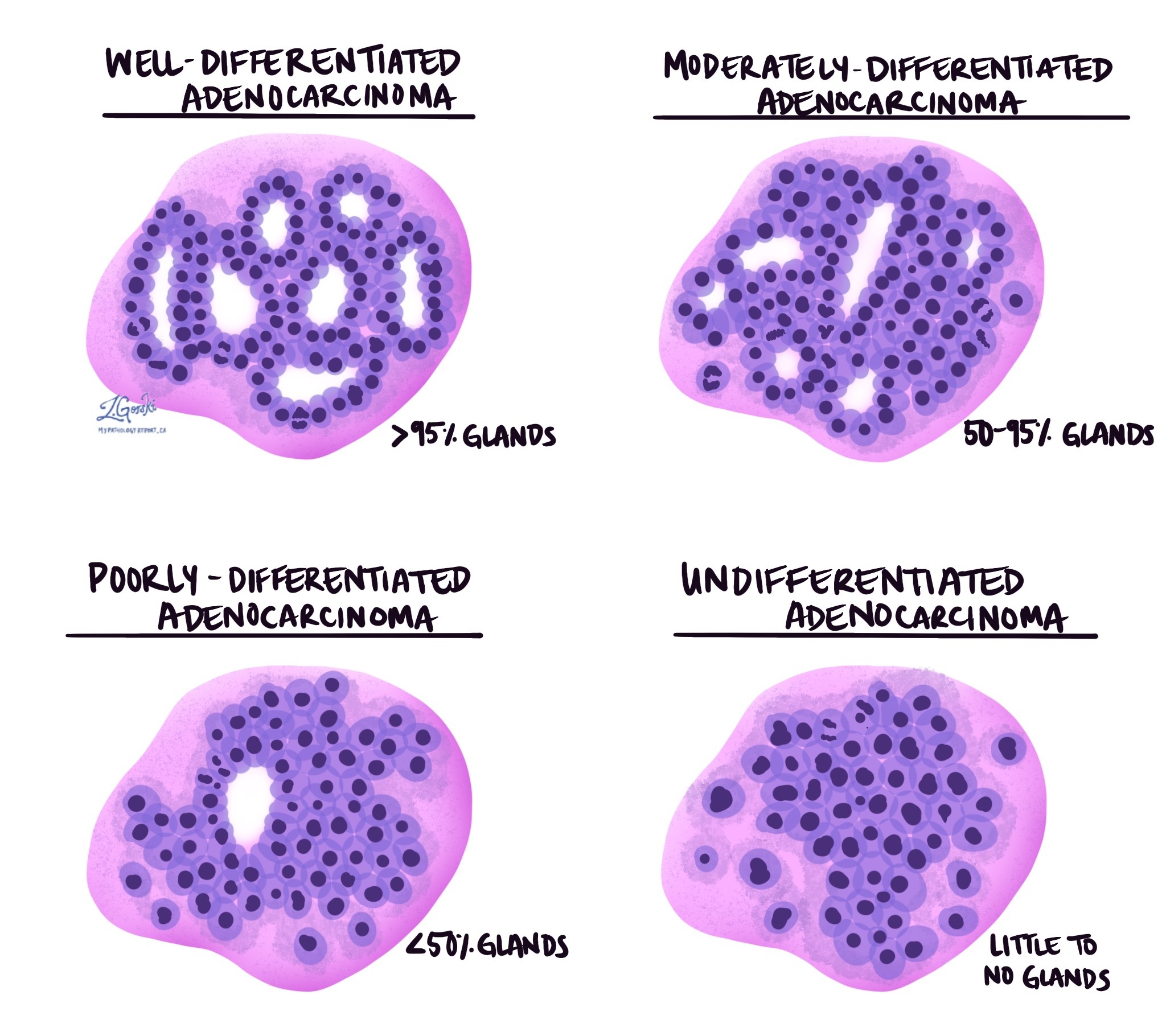

Tumour grade

Tumour grade describes how closely the tumour cells resemble normal colon cells. In colon adenocarcinoma, grade is based on how much of the tumour forms gland-like structures.

-

Grade 1 (well differentiated) – More than 95 percent of the tumour forms glands.

-

Grade 2 (moderately differentiated) – Between 50 and 95 percent of the tumour forms glands.

-

Grade 3 (poorly differentiated) – Less than 50 percent of the tumour forms glands.

-

Grade 4 (undifferentiated) – No gland formation is seen.

Higher-grade tumours are more aggressive and more likely to spread. The most recent World Health Organization guidelines also allow a simplified two-tier system in which low grade includes grades 1 and 2, and high grade includes grades 3 and 4.

Mucinous differentiation

Mucinous differentiation means the tumour contains a large amount of extracellular mucin, or mucus, outside the tumour cells. When more than 50% of the tumour is composed of mucin, it is classified as a mucinous adenocarcinoma. This subtype can behave more aggressively and may spread more easily.

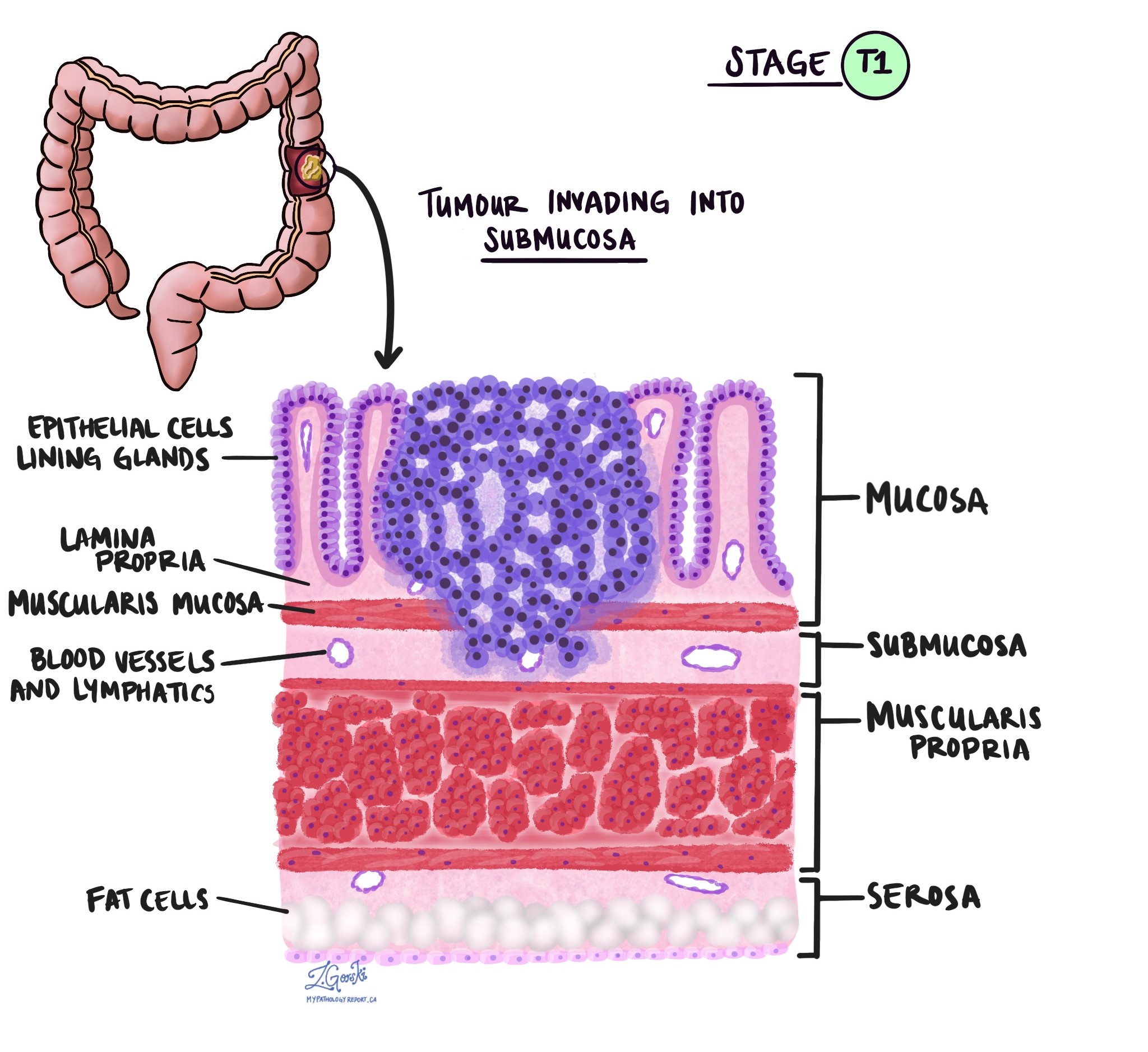

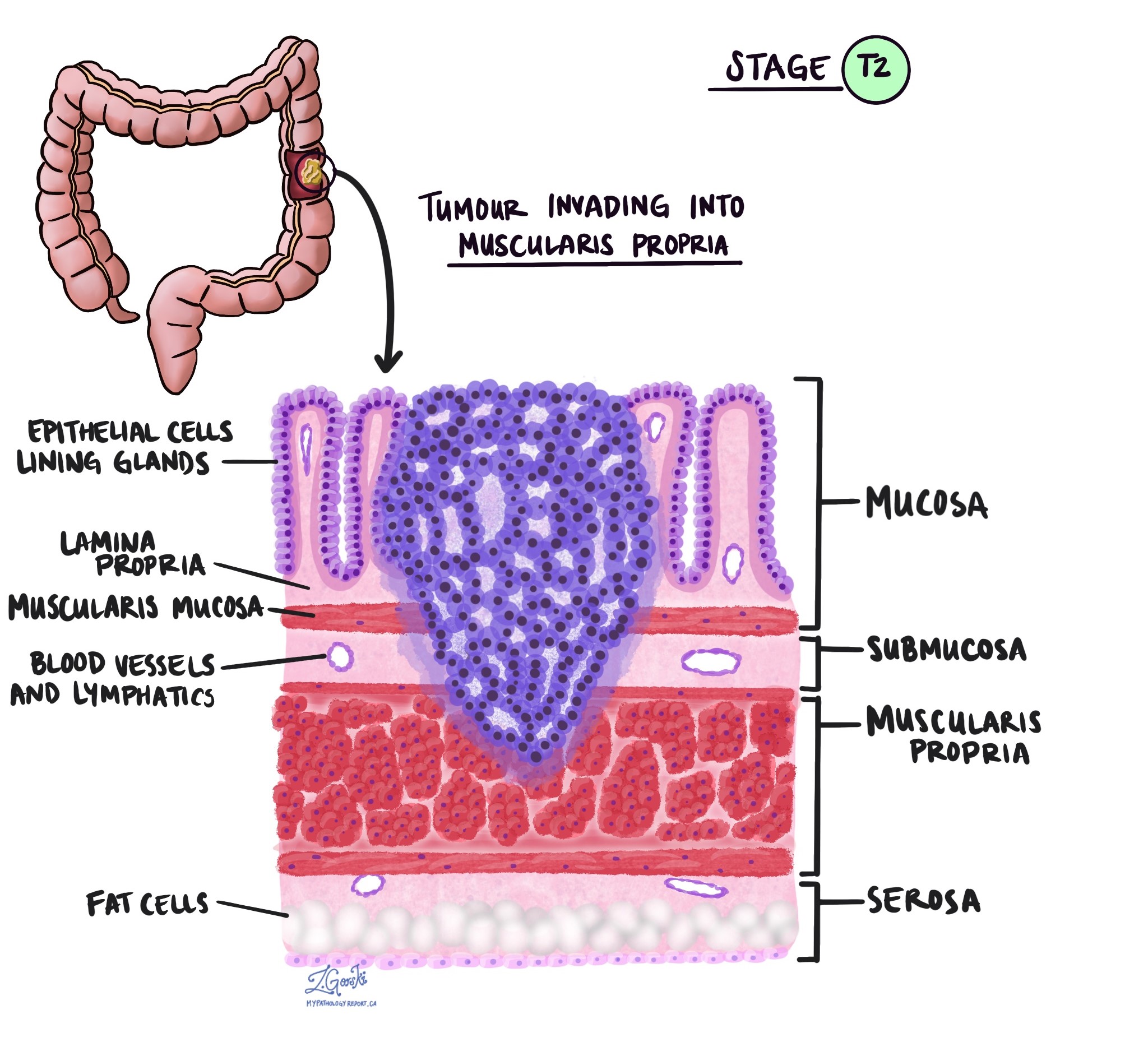

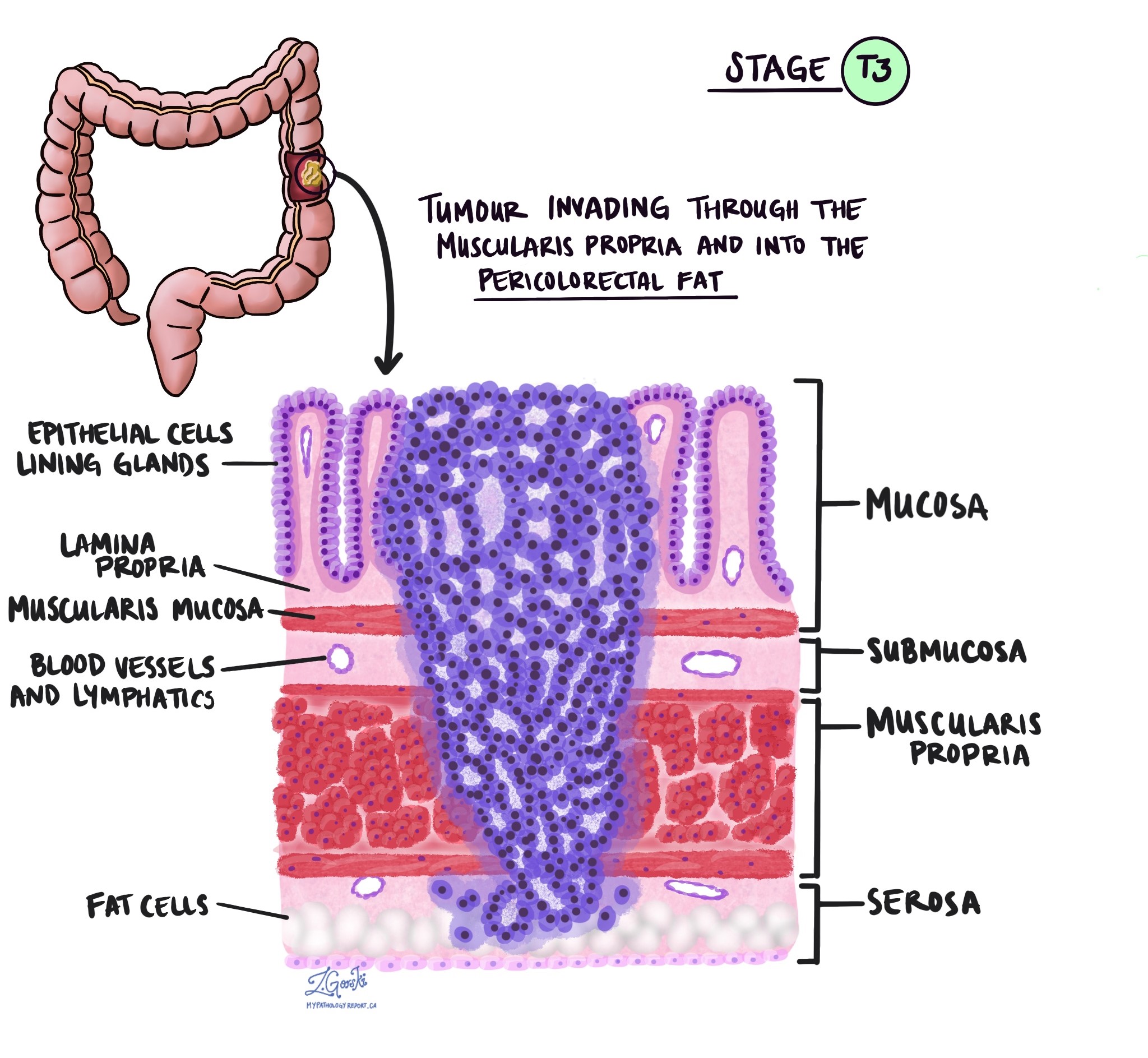

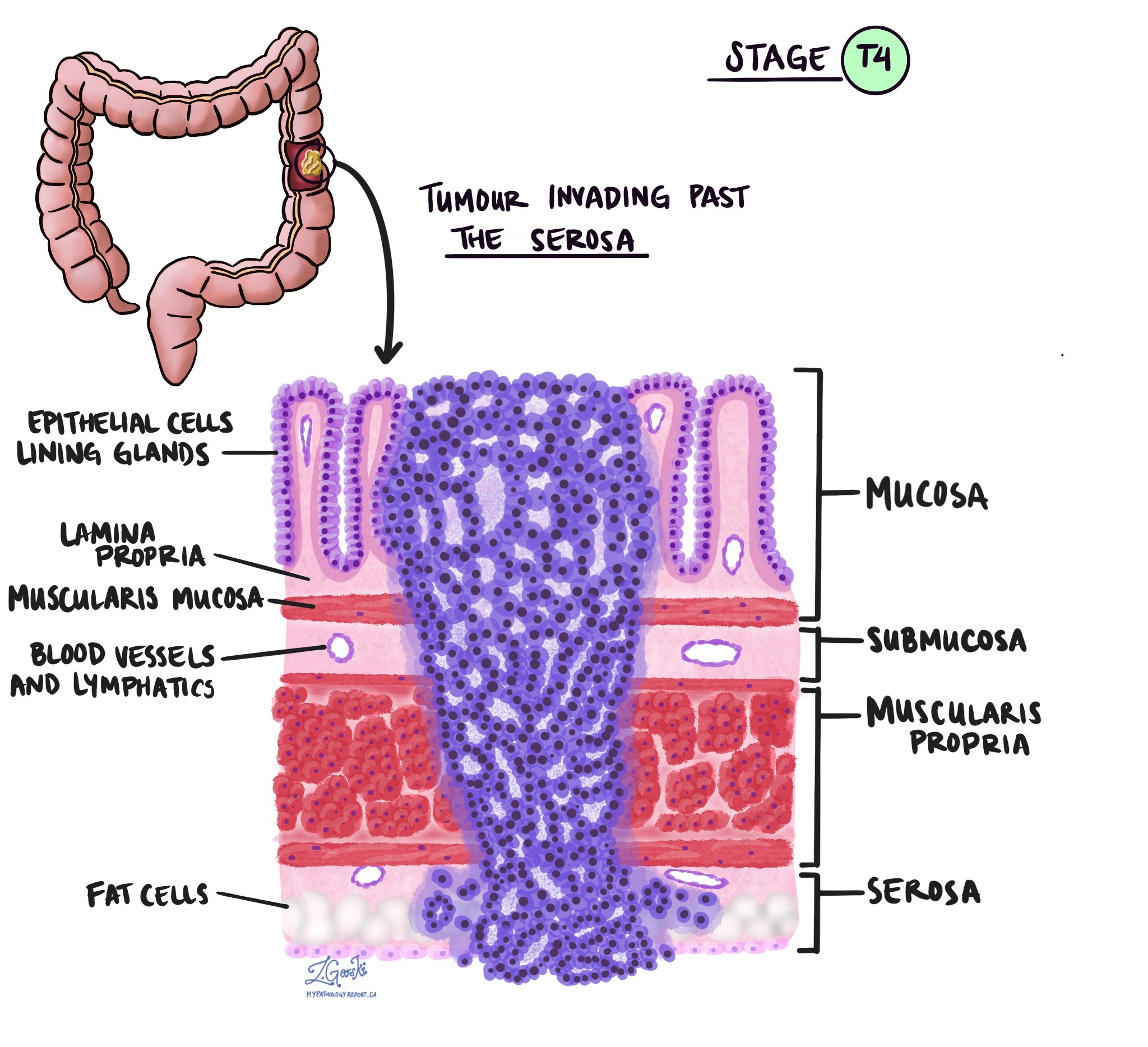

Level of invasion

Invasion describes how deeply the tumour has grown into the wall of the colon. Colon adenocarcinoma starts in the mucosa, the thin inner lining of the colon, and can spread into deeper layers.

The layers of the colon wall are described below to make their names on a pathology report easier to understand.

-

Mucosa – This inner lining contains the epithelial cells that form glands and where cancers begin.

-

Submucosa – This supportive layer of connective tissue lies just beneath the mucosa and contains blood vessels and lymphatic channels.

-

Muscularis propria – This thick muscle layer contracts to move waste through the colon.

-

Subserosal tissue – This layer is a thin band of fat or connective tissue outside the muscle in parts of the colon.

-

Serosa – This is the smooth outer surface that covers sections of the colon, although it is not present everywhere.

As a tumour grows into deeper layers, the likelihood of spreading to lymph nodes or distant organs increases. The deepest layer reached by the tumour is reported as the level of invasion and is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT). Pathologists determine this level only by examining tissue under the microscope. This information helps plan treatment and estimate the risk of the cancer returning.

Tumour budding

Tumour budding refers to single cancer cells or tiny clusters of cells seen at the advancing edge of the tumour under the microscope. The number of buds is counted and used to assign a low, intermediate, or high score. A high tumour budding score is associated with a greater risk of cancer spreading.

Lymphatic invasion

Lymphatic invasion means cancer cells are present inside lymphatic channels, which are tiny vessels that drain fluid and carry immune cells. A thin layer of cells lines these channels and do not usually contain red blood cells. Finding tumour cells inside lymphatic channels suggests a higher chance of spread to nearby lymph nodes. Pathologists may use immunohistochemistry, a special staining method, to highlight cancer cells in these tiny vessels.

Vascular invasion

Vascular invasion means cancer cells are present inside blood vessels. This can occur within the colon wall (intramural vascular invasion) or in surrounding tissue (extramural vascular invasion). Both are linked to a higher risk of the cancer spreading to other organs, such as the liver or lungs, and extramural vascular invasion is considered particularly important. Special stains may be used to confirm tumour cells within blood vessels.

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion means cancer cells are growing along or around a nerve. This feature is more often seen in advanced tumours and is associated with a higher risk that the cancer will spread or come back after treatment. Under the microscope, pathologists look for tumour cells that encircle at least one-third of the outside of a nerve.

Immune response

The body often mounts an immune response to a tumour by sending lymphocytes and other immune cells to surround it. When a strong immune response is seen under the microscope, it may suggest that the body is containing or slowing tumour growth. A specific pattern called a Crohn-like reaction shows groups of immune cells clustered near the tumour and is generally associated with a better outcome. Pathologists may use immunohistochemistry to assess immune cells, and although this is not always included in standard reports, the immune response is increasingly recognized as an important feature.

Margins

Margins are the cut edges of tissue removed during surgery. Pathologists examine margins to determine whether the tumour was removed entirely.

-

Proximal and distal margins describe the ends of the removed colon segment.

-

The circumferential resection margin (CRM) refers to the outermost soft-tissue edge, which is particularly important in rectal cancer.

-

The mesocolic margin is important for tumours in the caecum and adjacent colon.

A negative margin means no cancer cells are seen at the edge. A positive margin means cancer cells are present at the edge, suggesting that some tumour may remain and that additional treatment may be needed.

Treatment effect

If treatment such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy is given before surgery, the tumour may shrink. Pathologists assess the amount of viable tumour remaining and assign a treatment response score.

-

Score 0 – No viable cancer cells (complete response).

-

Score 1 – Single cells or rare small groups of cancer cells (near complete response).

-

Score 2 – Residual cancer with evidence of tumour regression, but more than single cells or rare small groups (partial response).

-

Score 3 – Extensive residual cancer with no obvious tumour regression (poor or no response).

This information helps doctors understand how well the tumour responded to therapy and whether additional treatment is appropriate.

Tumour deposits

Tumour deposits are small nodules of cancer cells located in the fat surrounding the colon or rectum in the lymphatic drainage area of the primary tumour. These deposits do not contain identifiable lymph node tissue or blood vessels. If a focus of tumour is found within a blood vessel,, it is classified as vascular invasion, and if it is found near a nerve,, it is classified as perineural invasion.

Tumour deposits are important because their presence increases the risk of spread. If tumour deposits are present but lymph nodes are negative, the nodal stage is N1c, regardless of the tumour stage. If positive lymph nodes are also present, the cancer is staged by the number of positive nodes, and the presence and number of tumour deposits are still recorded, as they are adverse prognostic factors that may influence treatment decisions.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs that filter lymphatic fluid and can trap cancer cells that have spread from the primary tumour. During surgery, lymph nodes near the tumour are removed and examined. Pathologists report lymph nodes as positive if they contain cancer and negative if they do not. If cancer is detected, the report may include the size of the largest tumour focus and whether there is extranodal extension, which means tumour cells have broken through the lymph node capsule into surrounding tissue.

Examining lymph nodes is essential for determining the pathologic nodal stage (pN) and for estimating the risk of spread to other parts of the body. This information helps doctors decide whether additional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation, or immunotherapy are needed.

Biomarkers for adenocarcinoma of the colon

Biomarkers are measurable features inside tumour cells—usually involving specific genes or proteins—that help doctors understand how the cancer behaves and how it may respond to treatment. In adenocarcinoma of the colon, biomarker testing is essential because the results can identify inherited cancer syndromes, determine whether immunotherapy is likely to be effective, and guide the use of targeted treatments. Biomarker testing is now a standard part of diagnosing and managing colorectal cancer.

What types of biomarkers are tested for colon adenocarcinoma?

Most biomarker tests for colon cancer focus on genetic mutations, gene rearrangements, and protein expression. These include tests that evaluate the tumour’s ability to repair DNA damage, tests that identify specific mutations in growth-promoting genes, and tests that help determine whether targeted treatments may be effective. Pathologists typically perform these tests on a biopsy sample or on the tumour removed during surgery using methods such as immunohistochemistry (IHC), which uses antibodies linked to dyes to highlight specific proteins, and molecular tests like PCR and next-generation sequencing (NGS), which analyze tumour DNA.

Mismatch repair proteins (MMR: MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, MSH6)

Mismatch repair (MMR) proteins are part of the cell’s DNA repair system. When any of these proteins—MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, or MSH6—are missing, the tumour becomes mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) and may accumulate DNA errors more quickly. This biomarker is important because dMMR tumours are more likely to respond to immunotherapy, and the finding may also indicate Lynch syndrome, an inherited condition that increases the risk of colon and other cancers.

Pathologists test for MMR proteins using immunohistochemistry. This test highlights each protein to show whether it is present in tumour cell nuclei. Loss of one or more proteins indicates mismatch repair deficiency.

Your report will describe the tumour as MMR-proficient (pMMR) if all proteins are present, or MMR-deficient (dMMR) if any are missing. The report may also specify which proteins are absent.

MLH1 promoter hypermethylation

MLH1 promoter hypermethylation is a chemical change that “turns off” the MLH1 gene, leading to loss of MLH1 and its partner PMS2. This causes mismatch repair deficiency but is usually a sporadic, non-inherited event. This biomarker is important because MLH1 hypermethylation helps distinguish sporadic dMMR tumours from tumours caused by Lynch syndrome.

Testing is performed using molecular methods such as methylation-specific PCR or next-generation sequencing to determine whether the MLH1 gene promoter is hypermethylated.

Your report will state whether MLH1 is hypermethylated or not hypermethylated. Tumours with MLH1 hypermethylation are usually not associated with Lynch syndrome.

KRAS and NRAS

KRAS and NRAS are genes that control cell growth. Mutations in these genes are common in colon cancer and are important because tumours with KRAS or NRAS mutations do not respond to anti-EGFR medications such as cetuximab or panitumumab. These mutations are also helpful for understanding tumour behaviour and choosing alternative treatments.

Testing is usually performed using PCR or next-generation sequencing to examine specific portions of the genes where mutations commonly occur, including codons 12, 13, 61, and 146.

Your report will describe the tumour as KRAS-positive or NRAS-positive if a mutation is found and KRAS-negative or NRAS-negative if no mutation is detected.

BRAF

BRAF is a gene in the same growth pathway as KRAS and NRAS. The BRAF V600E mutation is associated with more aggressive tumour behaviour and a higher likelihood of spread. This biomarker is important because BRAF-mutated tumours usually do not respond well to anti-EGFR therapy, and identifying a BRAF mutation also helps interpret mismatch repair results. A BRAF V600E mutation strongly suggests a sporadic tumour rather than Lynch syndrome.

BRAF testing is commonly performed using PCR or next-generation sequencing to detect the V600E mutation or other BRAF alterations.

Your report will state that the tumour is BRAF-positive if a mutation is present and BRAF-negative if no mutation is found.

PIK3CA

PIK3CA is a gene involved in pathways that help cells grow and survive. Mutations in PIK3CA occur in about 10–20% of colon cancers. This biomarker is important because PIK3CA mutations—especially when combined with KRAS or NRAS mutations—may reduce the benefit of anti-EGFR therapy. Some research suggests that patients with PIK3CA mutations may benefit from aspirin after surgery, although this is not yet standard care.

Testing for PIK3CA mutations is performed using next-generation sequencing to analyze the tumour’s DNA.

Your tumour will be described as PIK3CA-positive if a mutation is present and PIK3CA-negative if no mutation is detected.

PTEN

PTEN is a tumour suppressor gene that helps control cell growth. When PTEN is lost or stops functioning properly, tumour cells may grow more easily and may respond less well to anti-EGFR treatment. PTEN testing is important because it helps explain resistance to certain therapies.

PTEN can be assessed through molecular testing for gene alterations or by immunohistochemistry to check whether the PTEN protein is present in tumour cells.

Your report may describe the tumour as PTEN-intact if the protein is present or PTEN-loss if the protein is absent. Molecular test results may also indicate whether a mutation is present.

EGFR

EGFR is a protein on the surface of some cancer cells that helps control normal growth pathways. Anti-EGFR drugs such as cetuximab and panitumumab target this protein. Although EGFR itself is not used to select treatment in colon cancer, the testing is sometimes performed for research or clinical trial purposes. Treatment decisions rely more heavily on KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF, which predict whether anti-EGFR therapy will work.

When performed, EGFR testing may involve immunohistochemistry to evaluate protein expression or molecular testing to examine EGFR gene status.

Results may describe EGFR expression or mutation status, although these findings are not used routinely to guide treatment in colon adenocarcinoma.

PD-L1

PD-L1 is a protein on the surface of some tumour cells that helps the cancer hide from the immune system. Although PD-L1 testing plays an important role in some cancers, its usefulness in colon cancer is still being studied, and it is not yet routinely used to guide treatment. In certain situations, however, PD-L1 may provide additional information about the tumour’s ability to respond to immunotherapy.

Pathologists test for PD-L1 using immunohistochemistry, a method that uses antibodies linked to dyes to highlight the PD-L1 protein on tumour cells and nearby immune cells.

Results are often reported using a Combined Positive Score (CPS), which measures the percentage of tumour and immune cells showing PD-L1 staining. Higher CPS values indicate higher levels of PD-L1 expression, but the significance of these scores in colon cancer remains uncertain.

HER2 (ERBB2)

HER2 is a gene that helps control cell growth. In a small number of colon cancers—especially those without KRAS or BRAF mutations—the HER2 gene can become overactive. HER2 is important because tumours with HER2 overexpression or amplification may respond to HER2-targeted therapies, particularly in advanced disease or when other treatments are no longer effective.

Testing is usually performed using immunohistochemistry to evaluate HER2 protein levels and, when needed, additional molecular tests such as FISH or next-generation sequencing to determine whether the HER2 gene is amplified.

HER2 protein levels are reported using an IHC score of 0, 1+, 2+, or 3+.

-

Scores of 0 or 1+ are considered HER2-negative.

-

A score of 3+ is considered HER2-positive.

-

A score of 2+ is considered equivocal, and the tumour is tested further for HER2 gene amplification.

A tumour is classified as HER2-positive if it shows strong (3+) protein expression or if gene amplification is confirmed.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

Pathologic staging describes how far the cancer has spread when the tumour is removed and examined under the microscope. It uses three components: T (tumour depth), N (lymph nodes), and M (metastasis). Pathologists determine the pT and pN stages from the surgical specimen. The M stage is usually determined by imaging.

Tumour stage (pT)

The pT stage describes how deeply the tumour has grown into the wall of the colon or nearby tissues. The colon wall has several layers from the inside out: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, subserosa, and surrounding fat, and serosa (which is not present in all parts of the colon).

-

pT1 – The cancer has grown into the submucosa, which is the layer just beneath the inner lining.

-

pT2 – The cancer has grown into the muscularis propria, which is the thick muscle layer of the colon.

-

pT3 – The cancer has grown through the muscularis propria and into the fat and tissue surrounding the colon.

-

pT4a – The cancer has reached the outer surface of the colon, called the serosa, or has caused a perforation through the wall.

-

pT4b – The cancer has grown directly into nearby organs or structures such as the bladder, uterus, or abdominal wall.

Nodal stage (pN)

The pN stage describes whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes.

-

pN0 – No cancer is found in any of the lymph nodes that were examined.

-

pN1 – Cancer is found in one to three lymph nodes, or there are tumour deposits in surrounding tissues, even if all lymph nodes are negative.

-

pN1a – One lymph node contains cancer.

-

pN1b – Two or three lymph nodes contain cancer.

-

pN1c – No lymph nodes contain cancer, but tumour deposits are present in the fat or tissue near the colon.

-

pN2 – Cancer is found in four or more lymph nodes.

-

pN2a – Four to six lymph nodes are involved.

-

pN2b – Seven or more lymph nodes are involved.

If no lymph nodes were submitted or could not be evaluated, the stage may be listed as pNX, which means not assessable.

Why is staging important?

Staging helps your doctor understand how advanced the cancer is and what treatment is likely to be most effective. Lower stages,, such as pT1 or pN0,, suggest earlier disease and a better chance of cure. Higher stage,s, such as pT4 or pN,2, suggest more advanced disease and a higher risk of recurrence. Staging is considered alongside other features, including tumour grade, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, and biomarker results, to guide decisions on chemotherapy and follow-up care.

What happens after diagnosis?

After diagnosis, your healthcare team uses your pathology report, imaging results, and overall health to plan treatment. The team often includes a surgeon, a medical oncologist, a radiation oncologist, and a pathologist. Treatment depends on stage, tumour features, and biomarker results.

For many patients, surgery to remove the segment of colon containing the tumour and nearby lymph nodes is the first step. Chemotherapy may be recommended after surgery if the stage or tumour features suggest a higher risk of recurrence. In some situations—especially for rectal cancers or very bulky colon tumours—chemotherapy or radiation therapy may be given before surgery to shrink the tumour. Suppose the tumour carries specific biomarkers, such as dMMR, HER2 amplification, or specific BRAF alterations. In that case, your oncologist may discuss immunotherapy or targeted therapy as part of standard care or as part of a clinical trial.

After treatment, you will have regular follow-up, including clinic visits, blood tests, and periodic imaging. Colonoscopic surveillance is used to detect new polyps or early recurrence. If part of the colon was removed, your team will also monitor bowel function, nutrition, and iron or vitamin levels, and recommend strategies to optimize recovery.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What is the stage and grade of my tumour?

-

Were lymph nodes, lymphatic channels, or blood vessels involved?

-

Were the surgical margins negative, and was the tumour completely removed?

-

Do I need additional treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy, or targeted therapy?

-

Was the tumour tested for mismatch repair deficiency or other molecular markers such as KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, PTEN, HER2, and PD-L1?

-

What follow-up tests or procedures will I need, and how often will I need them?