by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Md Shahrier Amin, M.B.B.S., Ph.D.

June 9, 2025

IgA nephropathy, also known as Berger’s disease, is a kidney condition characterized by the accumulation of immunoglobulin A (IgA) in the kidneys. Antibodies are proteins that normally help fight infections. However, in IgA nephropathy, abnormal forms of IgA accumulate in the kidneys, causing inflammation and damage. This inflammation can eventually lead to kidney problems, including reduced kidney function or, in severe cases, kidney failure.

What do the kidneys do?

The kidneys are paired, bean-shaped organs located just below the ribs in the back of the abdomen and close to the spine. The kidneys’ most important function is to filter your blood. Removing waste products from the blood helps regulate your body’s electrolytes (sodium, potassium, and calcium) and water balance. These waste products and extra water are made into urine, which flows from the kidneys into the bladder.

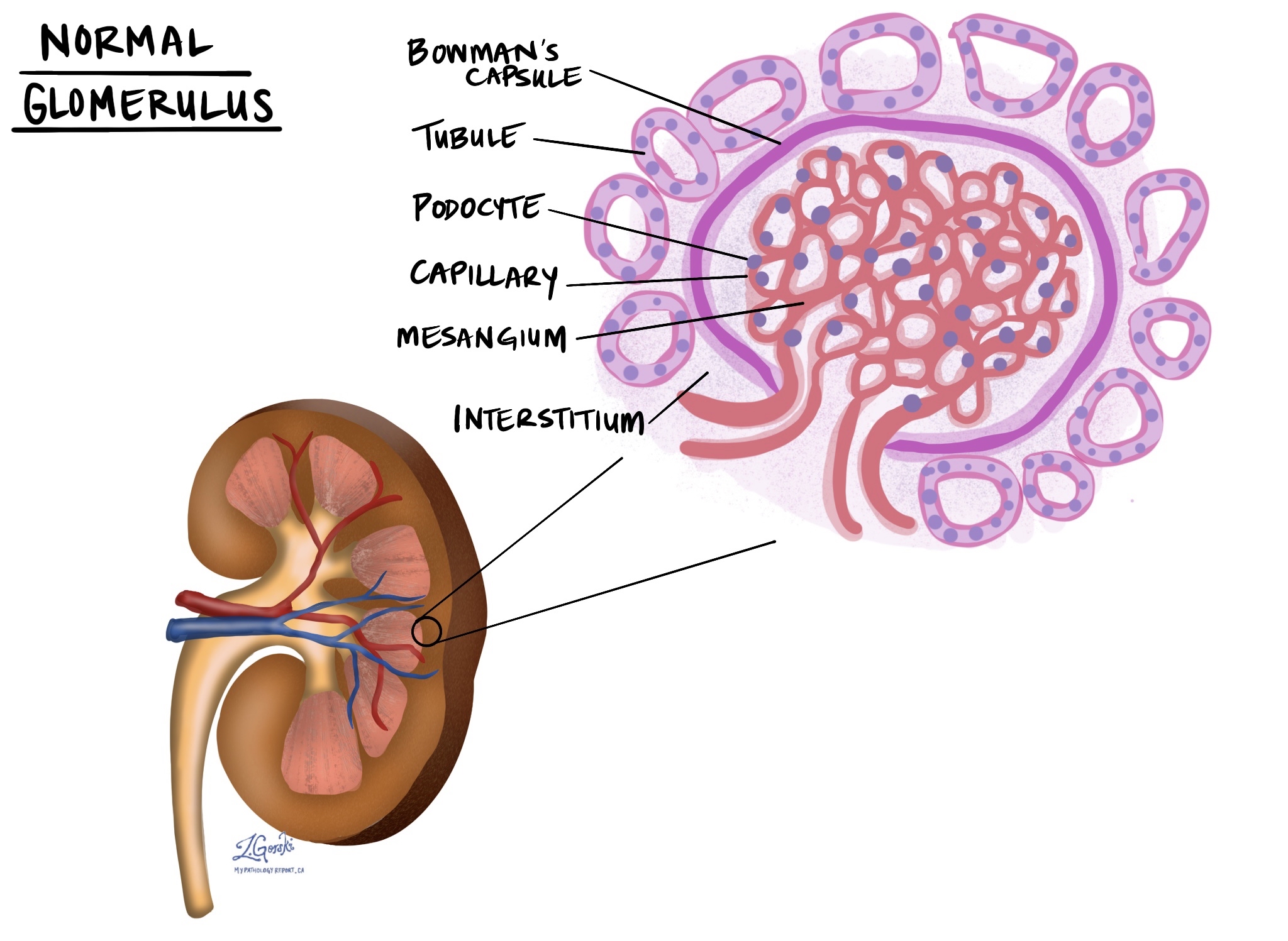

The job of filtering blood takes place in a part of the kidney called the nephron, and to ensure the job gets done, each kidney has millions of nephrons. At the heart of each nephron is a round structure called the glomerulus (multiple glomerulus are called glomeruli). Blood enters the glomerulus through a small blood vessel called an arteriole, which then splits up into many even smaller vessels called capillaries. Inside the glomeruli are specialized mesangial cells, which support the capillaries. Surrounding the capillaries and mesangial cells in the glomerulus is a crescent moon-shaped structure called Bowman’s capsule. The cells that cover the surface of Bowman’s capsule are called podocytes, and they are very important because they help decide what needs to stay in the blood and what needs to be removed.

What causes IgA nephropathy?

The exact cause of IgA nephropathy is not fully understood. However, it appears to result from an abnormal immune response, where IgA antibodies, particularly an abnormal form called galactose-deficient IgA, accumulate in the kidneys. These abnormal IgA antibodies can trigger inflammation and damage to kidney tissue. Genetic factors likely play a role, as this disease sometimes runs in families.

What are the symptoms of IgA nephropathy?

Many people with IgA nephropathy have mild or no symptoms at first. However, symptoms often include:

-

Blood in the urine (visible or detected by a urine test).

-

Foamy or bubbly urine due to protein leakage.

-

Swelling, particularly of the hands, feet, or face.

-

High blood pressure.

-

Fatigue and reduced kidney function.

Symptoms often appear after a respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. Over time, ongoing kidney inflammation can lead to permanent kidney damage or even kidney failure.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of IgA nephropathy is typically made by combining several pieces of information:

-

Clinical features: Your doctor will ask about your symptoms, medical history, and perform a physical examination.

-

Lab tests: Urine tests detect the presence of protein and blood in your urine. Blood tests measure kidney function and sometimes check for abnormal levels of antibodies.

-

Kidney biopsy: A kidney biopsy involves taking a tiny sample of kidney tissue, which is examined by a pathologist under a microscope. This biopsy is essential because it confirms the presence of IgA deposits and assesses the extent of kidney damage.

What do pathologists see under the microscope in IgA nephropathy?

Pathologists examine kidney biopsy samples using three different types of tests: light microscopy, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy. These tests are described in greater detail below.

Light microscopy

This test involves examining thin slices of kidney tissue that have been stained with special dyes such as hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Pathologists look for signs of inflammation, including swelling of kidney structures, an increased number of cells within the kidney’s filtering units (glomeruli), and scarring.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence involves staining the kidney tissue with antibodies tagged with fluorescent dyes. Under a special microscope, pathologists examine the kidney glomeruli for deposits of IgA antibodies, confirming the diagnosis of IgA nephropathy.

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy enables pathologists to visualize kidney structures with extremely high magnification. This test helps identify dense deposits of IgA in specific areas within the kidney glomeruli. These deposits have a distinctive appearance, helping to confirm the diagnosis.

Oxford Classification of IgA nephropathy

The Oxford Classification is a system pathologists use to grade the severity of IgA nephropathy based on biopsy findings. This classification helps doctors predict how the disease may progress and how aggressively it needs to be treated.

The classification evaluates five key features, summarized by the letters MEST-C:

-

M (Mesangial hypercellularity): Indicates how many extra cells are in a specific area of the glomeruli.

-

M0 (no significant increase).

-

M1 (increased cells present).

-

-

E (Endocapillary hypercellularity): Reflects swelling and increased cells within the tiny blood vessels inside glomeruli.

-

E0 (absent).

-

E1 (present).

-

-

S (Segmental glomerulosclerosis): Indicates areas of scarring involving parts of the glomeruli.

-

S0 (absent).

-

S1 (present).

-

-

T (Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis): Measures the amount of scarring and damage in the kidney’s supporting structures.

-

T0 (little or no damage).

-

T1 (moderate damage).

-

T2 (severe damage).

-

-

C (Crescents): Indicates severe inflammation causing a crescent-shaped buildup of cells within glomeruli.

-

C0 (no crescents).

-

C1 (crescents in less than 25% of glomeruli).

-

C2 (crescents in 25% or more of glomeruli).

-

Each of these features helps your doctor understand the level of activity and severity of your kidney disease. Higher scores generally indicate a greater risk of kidney function worsening over time.

Other changes that may be described in your report for IgA nephropathy

Pathologists often describe additional microscopic features that suggest chronic kidney damage. These features help your doctor determine how long your kidneys have been damaged and the likelihood of disease progression.

Number of glomeruli examined

Pathologists note how many glomeruli (kidney filtering units) were seen in your biopsy. Having enough glomeruli examined is important for an accurate assessment.

Global glomerulosclerosis

This means entire glomeruli have become completely scarred and can no longer function. A higher number of globally scarred glomeruli indicates more severe long-term kidney damage.

Segmental sclerosis

Segmental sclerosis means only part of a glomerulus is scarred. This feature indicates ongoing but less extensive damage, and it may progress to global sclerosis over time.

Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy

This describes scarring and shrinkage of the tissue around the tubules, the small tubes in the kidney that handle fluid and waste. Greater interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy mean that your kidneys have experienced prolonged damage.

Arteriosclerosis

Arteriosclerosis refers to the thickening and hardening of the kidneys’ blood vessels. This change restricts blood flow and suggests a long-term injury to the kidney blood vessels, commonly associated with high blood pressure and chronic kidney disease.

Arteriolar hyalinosis

This describes the buildup of protein-rich material in the walls of tiny blood vessels (arterioles) in the kidney. Arteriolar hyalinosis suggests long-term damage, often due to high blood pressure or diabetes, and is associated with chronic kidney injury.

Understanding these detailed biopsy results helps your doctor choose the most appropriate treatment and estimate how your condition may progress.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What does my biopsy show about the severity of my IgA nephropathy?

-

What are my Oxford Classification scores, and what do they mean for my treatment and outlook?

-

Do I need to start medication immediately?

-

How frequently will I need follow-up visits and kidney function testing?

-

Should I expect my kidney function to worsen over time?

-

Are there lifestyle changes I can make to protect my kidneys?

-

Do I need to manage other health conditions like high blood pressure or diabetes differently due to IgA nephropathy?

-

Is there anything specific I should watch for that would indicate worsening kidney disease?