by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

January 9, 2025

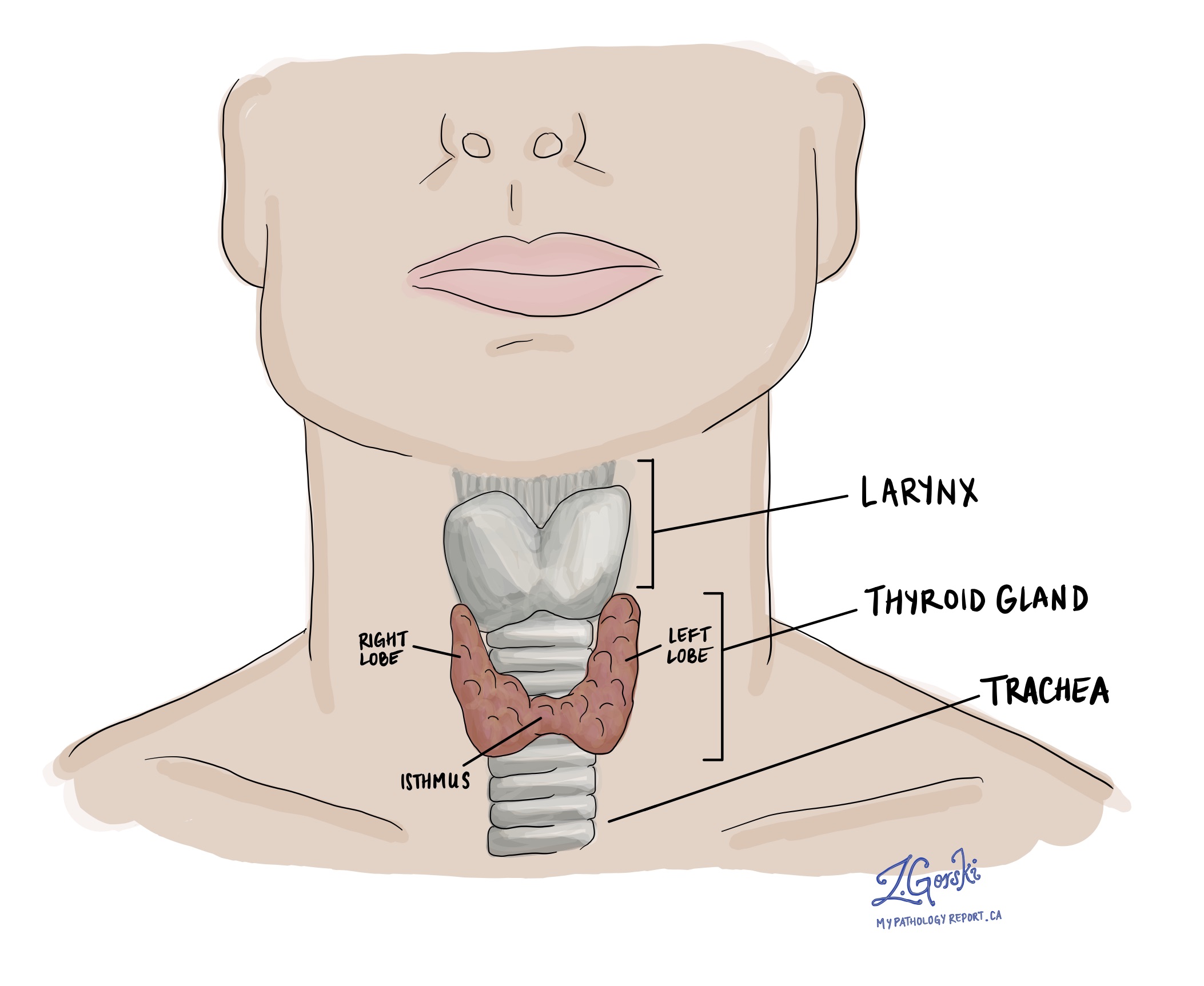

Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is the most common type of thyroid cancer, accounting for approximately 80% of all cases. The thyroid gland, a vital butterfly-shaped organ located in the front of the neck, plays an important role in regulating metabolic processes within the body. The term “papillary” comes from the cancer cells’ appearance under a microscope; most tumours contain tiny, finger-like projections called papillae.

What are the symptoms of papillary thyroid carcinoma?

Symptoms of papillary thyroid carcinoma may include:

- A lump or swelling in your neck that you can see or feel.

- Voice changes, like hoarseness.

- Trouble with swallowing or breathing.

What causes papillary thyroid carcinoma?

The cause of papillary thyroid carcinoma isn’t fully understood. However, it seems to involve a combination of both genetic changes and environmental risk factors, such as exposure to ionizing radiation and dietary influences. This type of cancer is also much more common in young women.

How is the diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma made?

The diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma involves several steps:

- Physical examination: Evaluation of the neck for lumps or nodules.

- Ultrasound: Imaging to assess the thyroid and surrounding structures, providing details about the nodule’s size, composition, and vascularity.

- Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy: A sample of cells is taken from the nodule and examined under a microscope. However, FNA cannot definitively distinguish between benign and malignant follicular tumours.

- Thyroid function tests: Blood tests to measure levels of thyroid hormones and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

- Surgical removal of the nodule: Surgery is often required to diagnose papillary thyroid carcinoma. This usually involves removing half of the thyroid gland. The nodule is then sent to a pathologist for histopathological examination.

Subtypes of papillary thyroid carcinoma

Not all papillary thyroid carcinomas are the same. In pathology, the term “subtype” (or “variant”) refers to tumours that differ in their appearance under the microscope, their behaviour, and, sometimes, their response to treatment. Some subtypes grow very slowly and are less likely to spread, while others can be more aggressive.

Understanding the specific subtype of papillary thyroid carcinoma a person has is crucial for several reasons. It helps doctors predict how the cancer might behave, choose the most effective treatment plan, and provide the most accurate information about prognosis. In essence, knowing the subtype paints a clearer picture of what to expect and how to tackle it. The following sections provide an overview of the most common subtypes of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Classic subtype

The classic subtype is the most common type of papillary thyroid carcinoma, which is why it is also known as the conventional subtype. The tumour consists of many finger-like projections of tissue called papillae. Tumour cells from this subtype commonly spread to lymph nodes in the neck.

Infiltrative follicular subtype

The infiltrative follicular subtype is another common type of papillary thyroid carcinoma. The tumour cells in this variant grow in small, circular groups called follicles, which can resemble the normal follicles in the thyroid gland. Unlike invasive encapsulated follicular subtype papillary thyroid carcinoma, the infiltrative follicular subtype is not surrounded by a thin layer of tissue called a tumour capsule.

Tall cell subtype

The tall cell subtype of papillary thyroid carcinoma is an aggressive tumour that commonly spreads outside the thyroid gland to lymph nodes. To diagnose this subtype, the tumour cells should be at least three times taller than they are wide. This type of tumour is more common in older adults and is rarely seen in children.

Hobnail subtype

The hobnail subtype of papillary thyroid carcinoma is an aggressive tumour that commonly spreads outside of the thyroid gland to lymph nodes and distant parts of the body, such as the bones. It is made up of tumour cells that appear to hang off the surface of the papillae within the tumour.

Solid/trabecular subtype

The solid/trabecular subtype of papillary thyroid carcinoma is an aggressive tumour that is more likely to spread to distant body parts such as the lungs. The tumour cells in the solid/trabecular variant grow in large groups or long chains. Pathologists describe these patterns of growth as solid or trabecular.

Oncocytic subtype

The tumour cells in the oncocytic subtype of papillary thyroid carcinoma are called oncocytic because they are larger than normal cells and look bright pink when viewed under a microscope. The prognosis for this subtype is similar to that of the classic subtype.

Diffuse sclerosing subtype

The diffuse sclerosing subtype of papillary thyroid carcinoma is more common in children and young adults. Unlike other tumours, which often only involve one side, the diffuse sclerosing variant is likely to affect both sides (right and left lobes) of the thyroid. Compared to the classic variant, the tumour cells in the diffuse sclerosing variant are more likely to spread outside the thyroid gland to distant parts of the body.

Columnar subtype

The columnar subtype is a rare but aggressive type of papillary thyroid carcinoma that commonly spreads to lymph nodes and other parts of the body. It consists of tumour cells that are taller than they are wide, and the cells overlap in a way that pathologists describe as “pseudostratified.”

Genetic changes associated with papillary thyroid carcinoma

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, like many cancers, often involves changes in the DNA of thyroid cells. These changes enable the cells to grow faster and less under control than normal cells.

Some of the common genetic changes associated with this type of cancer include:

- BRAF mutations: The BRAF gene makes a protein that is part of a signalling pathway known as MAPK, which helps regulate cell growth and division. A mutation (change) in the BRAF gene, particularly the BRAF V600E mutation, results in an abnormal version of the BRAF protein that is always active. This constant activity signals thyroid cells to grow and divide uncontrollably, leading to cancer. BRAF mutations are one of the most common genetic changes seen in papillary thyroid carcinoma and are associated with more aggressive forms of the disease.

- RET/PTC rearrangements: The RET gene codes for a type of receptor protein on the surface of cells, which is involved in cell growth signals. In papillary thyroid carcinoma, parts of the RET gene can become abnormally connected (rearranged) with parts of other genes, creating fusion genes called RET/PTC rearrangements. These rearrangements produce abnormal proteins that activate signalling pathways, such as MAPK, even without the normal external signals that typically initiate the process, leading to uncontrolled cell growth and cancer.

- RAS mutations: RAS genes (KRAS, NRAS, HRAS) produce proteins important in regulating cell division, growth, and death. When mutated, RAS proteins can become permanently active, continuously telling cells to grow and divide. This unregulated cell growth can lead to the formation of tumours. RAS mutations are found in a variety of cancers, including some cases of papillary thyroid carcinoma, and can contribute to both the initiation and progression of the disease.

Tumour size

After the tumour is removed completely, it will be measured. The tumour is usually measured in three dimensions, but your report will describe only the largest dimension. For example, if the tumour measures 4.0 cm by 2.0 cm by 1.5 cm, your report will describe it as 4.0 cm. Tumour size is important for papillary thyroid carcinoma because it determines the pathologic tumour stage (pT). Larger tumours are more likely to spread to other body parts, such as lymph nodes.

Multifocal tumours

It is not unusual for more than one tumour to be found in the same thyroid gland. Multifocal is a word pathologists use to describe finding more than one tumour of the same subtype in the thyroid gland. If different subtypes of papillary thyroid carcinoma are found, each tumour will be described separately in your report. When more than one tumour is found, only the largest tumour is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

Extrathyroidal extension

Extrathyroidal extension (ETE) refers to the spread of cancer cells beyond the thyroid gland into surrounding tissues. It is an important prognostic factor in thyroid cancer, as it can significantly influence both the staging and management of the disease.

Extrathyroidal extension is classified into two types based on the extent of the spread:

- Microscopic extrathyroidal extension: This extension is only visible under a microscope and indicates that the cancer has spread just beyond the thyroid capsule but cannot be seen with the naked eye. It may involve minimal infiltration into surrounding soft tissues.

- Macroscopic (or gross) extrathyroidal extension: This type is visible to the naked eye or detectable during surgery. It involves more obvious and extensive invasion into neighbouring structures such as muscles, trachea, esophagus, or major blood vessels.

Extrathyroidal extension is important for the following reasons:

- Prognosis: Macroscopic (gross) extrathyroidal extension is associated with a worse prognosis. It suggests a more aggressive cancer that is more likely to recur and metastasize.

- Staging: Extrathyroidal extension impacts the staging of thyroid cancer. For instance, in the TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) classification system used for thyroid cancer, macroscopic extrathyroidal extension results in a higher pathologic tumour stage (pT).

- Treatment and follow-up: Macroscopic (gross) extrathyroidal extension might lead to more aggressive treatment strategies and closer follow-up to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Vascular invasion (angioinvasion)

Vascular invasion (also known as angioinvasion) in the context of papillary thyroid carcinoma of the thyroid gland refers to the spread of cancer cells into blood vessels outside the tumour. Vascular invasion is a marker of more aggressive behaviour and has important implications for the prognosis and management of the cancer.

Importance of vascular invasion:

- Metastatic potential: Vascular invasion increases the risk of cancer cells spreading to distant sites in the body through the bloodstream. This can lead to the formation of metastases, especially in organs like the lungs and bones, which are common sites for thyroid cancer metastasis.

- Prognosis: Vascular invasion is generally associated with a poorer prognosis. It indicates that the cancer is more aggressive and capable of spreading to distant parts of the body.

- Treatment decisions: Identifying vascular invasion can influence treatment decisions. For instance, it may lead to the use of higher doses of radioactive iodine or the inclusion of systemic therapies to address potential metastatic disease.

- Follow-up and monitoring: Given their higher risk profile, patients with evidence of vascular invasion may require closer follow-up and more intensive monitoring for recurrence or spread of the disease.

Lymphatic invasion

Lymphatic invasion in the context of papillary thyroid carcinoma refers to the infiltration and spread of cancer cells into the lymphatic system. Cancer cells that enter the lymphatic system can travel to lymph nodes. It is very common to find lymphatic invasion with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Unlike vascular invasion, lymphatic invasion is not necessarily associated with a more aggressive disease or a worse prognosis.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests that the tumour was entirely removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread through lymphatic vessels from a tumour to lymph nodes. For this reason, lymph nodes are commonly removed and examined under a microscope to look for cancer cells. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to another part of the body, such as a lymph node, is called metastasis.

Cancer cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour, although lymph nodes far away can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are typically removed only if they are enlarged, and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancer cells in them.

Neck dissections

A neck dissection is a surgical procedure that involves removing lymph nodes from the neck. The lymph nodes removed usually come from different neck areas, and each region is called a level. The levels in the neck include 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Your pathology report will often describe how many lymph nodes were seen in each level sent for examination. Lymph nodes on the same side as the tumour are called ipsilateral, while those on the opposite side of the tumour are called contralateral.

How the lymph nodes will be described in your pathology report

If any lymph nodes are removed from your body, they will be examined under the microscope by a pathologist, and the examination results will be described in your report. “Positive” means that cancer cells were found in the lymph node. “Negative” indicates that no cancer cells were found. If cancer cells are found in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) may also be included in your report. Extranodal extension means that the tumour cells have broken through the capsule outside of the lymph node and spread into the surrounding tissue.

Why is the examination of lymph nodes important?

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information determines the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment, such as radioactive iodine, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy, is required.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

The pathologic stage for papillary thyroid carcinoma can only be determined after the entire tumour has been surgically removed and examined under the microscope by a pathologist. The stage is divided into three parts: tumour stage (pT), which describes the tumour; nodal stage (pN), which describes any lymph nodes examined; and metastatic stage (pM), which describes tumour cells that have spread to other parts of the body. Most pathology reports will include information about the tumour and nodal stages. The overall pathologic stage is important because it helps your doctor determine the best treatment plan and predict the outlook for recovery.

Tumour stage (pT)

- T0: No evidence of primary tumour.

- T1: The tumour is 2 cm (about 0.8 inches) or smaller in its greatest dimension and confined to the thyroid.

- T1a: The tumour is 1 cm (about 0.4 inches) or smaller.

- T1b: The tumour is larger than 1 cm but not larger than 2 cm.

- T2: The tumour is larger than 2 cm but not larger than 4 cm (about 1.6 inches) and is still inside the thyroid.

- T3: The tumour is larger than 4 cm or has minimal extension beyond the thyroid gland.

- T3a: The tumour is larger than 4 cm but is still confined to the thyroid.

- T3b: The tumour shows gross extrathyroidal extension (it has spread into the muscles outside of the thyroid).

- T4: This indicates advanced disease.

- T4a: The tumour extends beyond the thyroid capsule to invade subcutaneous soft tissues, the larynx (voice box), trachea (windpipe), esophagus (food pipe), or recurrent laryngeal nerve (a nerve that controls the voice box).

- T4b: The tumour invades prevertebral space (area in front of the spinal column), and encases the carotid artery or the mediastinal vessels (major blood vessels).

Nodal stage (pN)

- N0: No regional lymph node metastasis (the cancer hasn’t spread to nearby lymph nodes).

- N1: There is metastasis to regional lymph nodes (near the thyroid).

- N1a: Metastasis is limited to lymph nodes around the thyroid (pretracheal, paratracheal, prelaryngeal/Delphian, and/or perithyroidal lymph nodes).

- N1b: Metastasis to other cervical (neck) or superior mediastinal lymph nodes (lymph nodes in the upper chest).