by Bibianna Purgina, MD FRCPC

August 3, 2022

What is a solitary fibrous tumour?

A solitary fibrous tumour (SFT) is a type of tumour that develops from cells normally found in connective tissue. Most behave as non-cancerous tumours but some can behave in an aggressive manner that is more similar to cancer. Your pathologist will carefully examine your tissue sample to look for features that will help predict how the tumour will behave over time.

What causes a solitary fibrous tumour?

SFT is caused by the fusion (combination) of two genes, NAB2 and STAT6. The new fusion gene leads to the production of proteins that allow the tumour cells to grow and divide. At this time, doctors do not know what causes the NAB2-STAT6 fusion gene to form.

What are the symptoms of a solitary fibrous tumour?

Most SFTs do not cause any symptoms until the tumour becomes large enough to put pressure on surrounding normal organs and tissues. When this happens the symptoms depend on the location of the tumour. Tumours in the abdomen may cause abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation. Tumours in the pelvis can make it difficult to urinate. Tumours in the head and neck can cause headache, sinus pain and pressure, nasal congestion, and changes in vision.

Where are solitary fibrous tumours normally found?

These tumours typically occur in adults and can develop anywhere in the body. Common locations include the extremities (arms and legs), abdomen, pelvis, and the head and neck. SFTs often develop deep inside the body which makes them difficult to see without medical imaging such as a CT scan or MRI.

Is a solitary fibrous tumour a type of cancer?

Most SFTs behave as non-cancerous tumours. However, 10 – 30% of tumours will behave more like cancers by regrowing at the original location or spreading to other parts of the body over time. After examining the tumour under the microscope, pathologists calculate a risk assessment score to help predict if the tumour will regrow or spread (see risk assessment below).

How is the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumour made?

The diagnosis is usually made after a small sample of the tumour is removed in a procedure called a biopsy. The tissue sample is then sent to a pathologist who examines it under a microscope. Additional tests such as immunohistochemistry and molecular testing such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) may also be performed to look for the NAB2-STAT6 fusion gene and confirm the diagnosis. In some situations, the diagnosis is made after the entire tumour is surgically removed in a procedure called an excision or resection.

What does risk stratification mean for solitary fibrous tumour?

Risk stratification (also called risk assessment) is a method used to predict how an SFT will behave over time. Risk stratification can only be performed after the tumour has been examined under the microscope by a pathologist. Risk stratification uses a combination of clinical and pathologic information including your age, tumour size, necrosis (a type of tumour cell death), and mitoses (tumour cells dividing to create new tumour cells). Each one of these variables is given a number of points (from 0 to 3) and the total number of points is used to determine the risk that the tumour will metastasize (spread) to another part of the body. Using the system, the risk is divided into three levels – low (0 – 3 points), intermediate (4 or 5 points), and high (6 or 7 points).

What is a malignant solitary fibrous tumour?

Malignant SFT is a term used to describe a tumour that shows definitive malignant (cancerous) features. This term can also be used to describe an SFT that has already metastasized (spread) to other parts of the body.

What does a solitary fibrous tumour look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, the tumour cells of SFT look similar to the cells that make up normal fibrous connective tissue. These cells are called fibroblasts. The fibroblasts in a solitary fibrous tumour are arranged in what pathologists describe as a “patternless pattern”. Lots of small branching small blood vessels are also seen in the tumour. Pathologists sometimes describe these small blood vessels as having a “hemangiopericytoma-like” or “staghorn” vascular pattern.

How is the size of the tumour measured and why is it important?

The size of the tumour can only be measured after the entire tumour has been surgically removed. The tumour is typically measured in three dimensions but only the largest dimension will be included in your report. For example, if the tumour measures 5.0 cm by 3.2 cm by 1.1 cm, the report may describe the tumour size as 5.0 cm in the greatest dimension. The size of the tumour is important because it is used to determine the risk assessment score (see above).

What does tumour extension mean?

Most SFTs are usually well-defined tumours which means they are separated from the normal surrounding tissue. However, tumours with cancerous features can grow into or around neighbouring muscles, bone and blood vessels. This is called tumour extension. Your pathologist will examine samples of the surrounding tissues under the microscope to look for tumour cells. Any surrounding organs or tissues that contain tumour cells will be described in your report.

What is a margin?

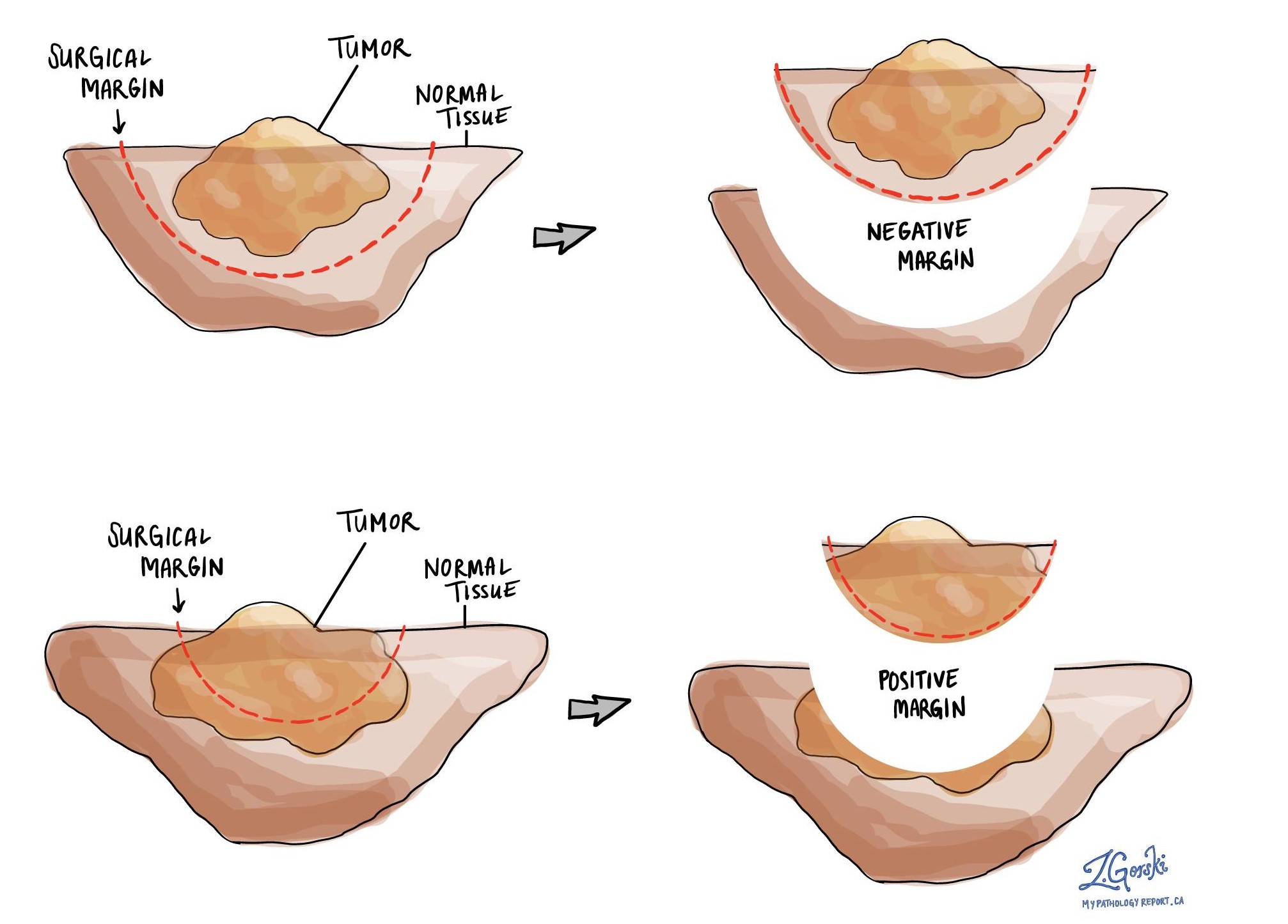

A margin is any tissue that was cut by the surgeon to remove the tumour from your body. Depending on the type of surgery you have had, the margins can include bones, muscles, blood vessels, and nerves that were cut to remove the tumour from your body. All margins will be very closely examined under the microscope by your pathologist to determine the margin status.

A margin is called negative when there are no tumour cells at the edge of the cut tissue. A margin is called positive when there are tumour cells at the edge of the cut tissue. A positive margin is associated with a higher risk that the tumour will recur in the same site after treatment (local recurrence).

What does treatment effect mean?

If you received chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy before the operation to remove the tumour, your pathologist will examine all the tissue sent to pathology to see how much of the tumour was still alive at the time it was removed from the body. Pathologists use the term viable to describe tissue that was still alive at the time it was removed from the body. In contrast, pathologists use the term non-viable to describe tissue that was not alive at the time it was removed from the body. Most commonly, your pathologist will describe the percentage of tumours that is non-viable.

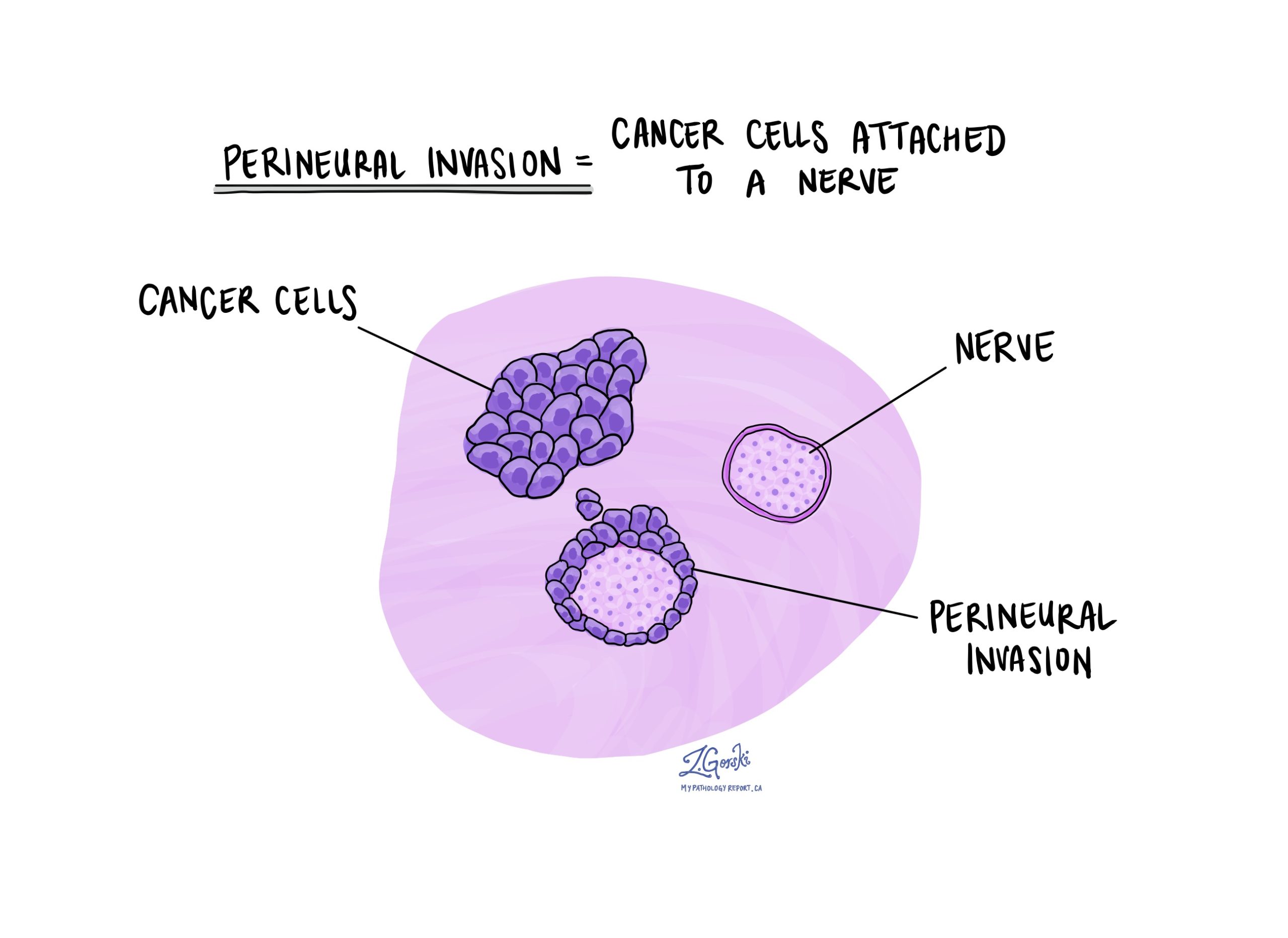

What is perineural invasion?

Perineural invasion means that tumour cells were seen attached to a nerve. Nerves are found all over the body and they are responsible for sending information (such as temperature, pressure, and pain) between your body and your brain. Perineural invasion is important because tumour cells that have become attached to a nerve can spread into surrounding tissues by growing along the nerve. This increases the risk that the tumour will regrow after treatment.

What is lymphovascular invasion?

Lymphovascular invasion means that tumour cells were seen inside of a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. Lymphovascular invasion is important because tumour cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other parts of the body such as lymph nodes or the lungs. SFT very rarely shows lymphovascular invasion. However, when found it is associated with a higher risk that the tumour cells will spread to lymph nodes.