by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

April 13, 2023

What is a spermatocytic tumour?

Spermatocytic tumour is a rare type of testicular cancer that is typically seen in men over 50 years of age. Unlike other types of testicular cancers, spermatocytic tumour also never metastasizes (spreads) to other parts of the body and most patients are cured with surgery alone.

What type of tumour is spermatocytic tumour?

Spermatocytic tumour is considered a type of germ cell tumour because it develops from germ cells normally found in the testicle.

Why is this tumour called “spermatocytic”?

This type of cancer is called “spermatocytic” because when examined under the microscope the tumour cells look similar to developing sperm cells called spermatogonia or spermatocytes.

Is spermatocytic tumour benign or malignant?

Spermatocytic tumour is a malignant (cancerous) tumour, however, unlike other types of cancer, the tumour cells rarely metastasize (spread) to other parts of the body.

What are the symptoms of spermatocytic tumour?

The most common symptom of a spermatocytic tumour is an enlarged but painless testicle.

What causes spermatocytic tumour?

The cause of spermatocytic tumour remains unknown. However, a significant percentage of tumours harbor a genetic change called an amplification involving a male-specific gene called DMRT1. How this alteration occurs is currently being investigated.

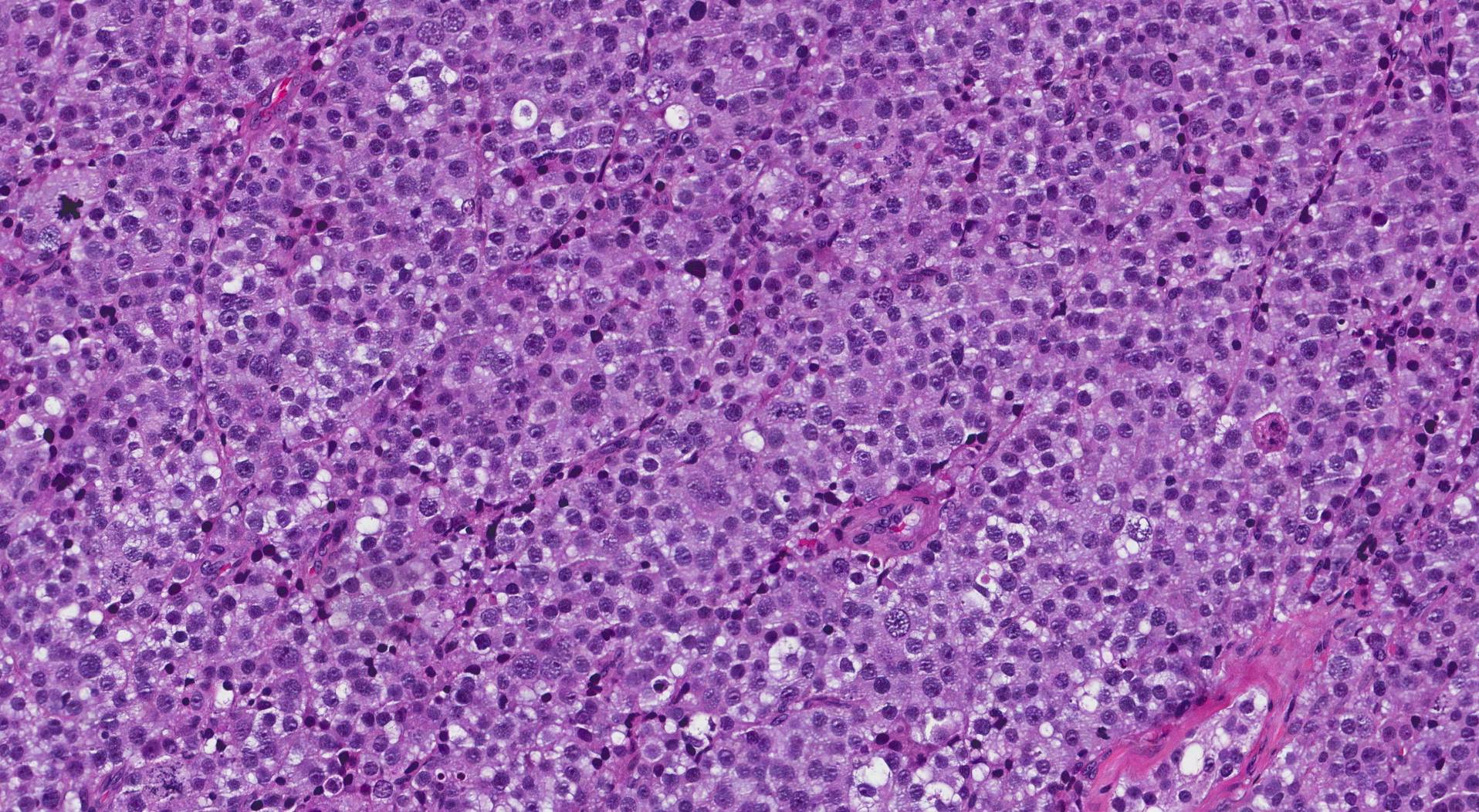

What does spermatocytic tumour look like under the microscope?

When examined under the microscope, spermatocytic tumour is made up of three types of cells classified on the basis of their size: small cells, intermediate cells, and giant cells. The tumour cells are often arranged in large groups called sheets or nodules. Dividing tumour cells called mitotic figures are commonly seen.

What does it mean if a spermatocytic tumour shows sarcomatous differentiation?

Sarcomatous differentiation in a spermatocytic tumour means that some of the cells in the tumour have changed into a more aggressive type of cancer called a sarcoma. Tumours that show sarcomatous differentiation frequently metastasize (spread) to other parts of the body, most commonly the lungs.

How is the tumour measured and why is the tumour size important?

These tumours are measured in three dimensions, but only the largest dimension is typically included in the report. For example, if the tumour measures 5.0 cm by 3.2 cm by 1.1 cm, the report may describe the tumour size as 5.0 cm in the greatest dimension. The tumour size is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

What does tumour extension mean and why is it important?

Tumour extension means the tumour has grown directly into tissues surrounding the testicle including the tunica vaginalis, hilar soft tissue, spermatic cord, or scrotum. Tumour extension is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

What is lymphovascular invasion?

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells were seen inside a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. The lymphatic vessels connect with small immune organs called lymph nodes that are found throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because cancer cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other parts of the body such as lymph nodes or the lungs and because it is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

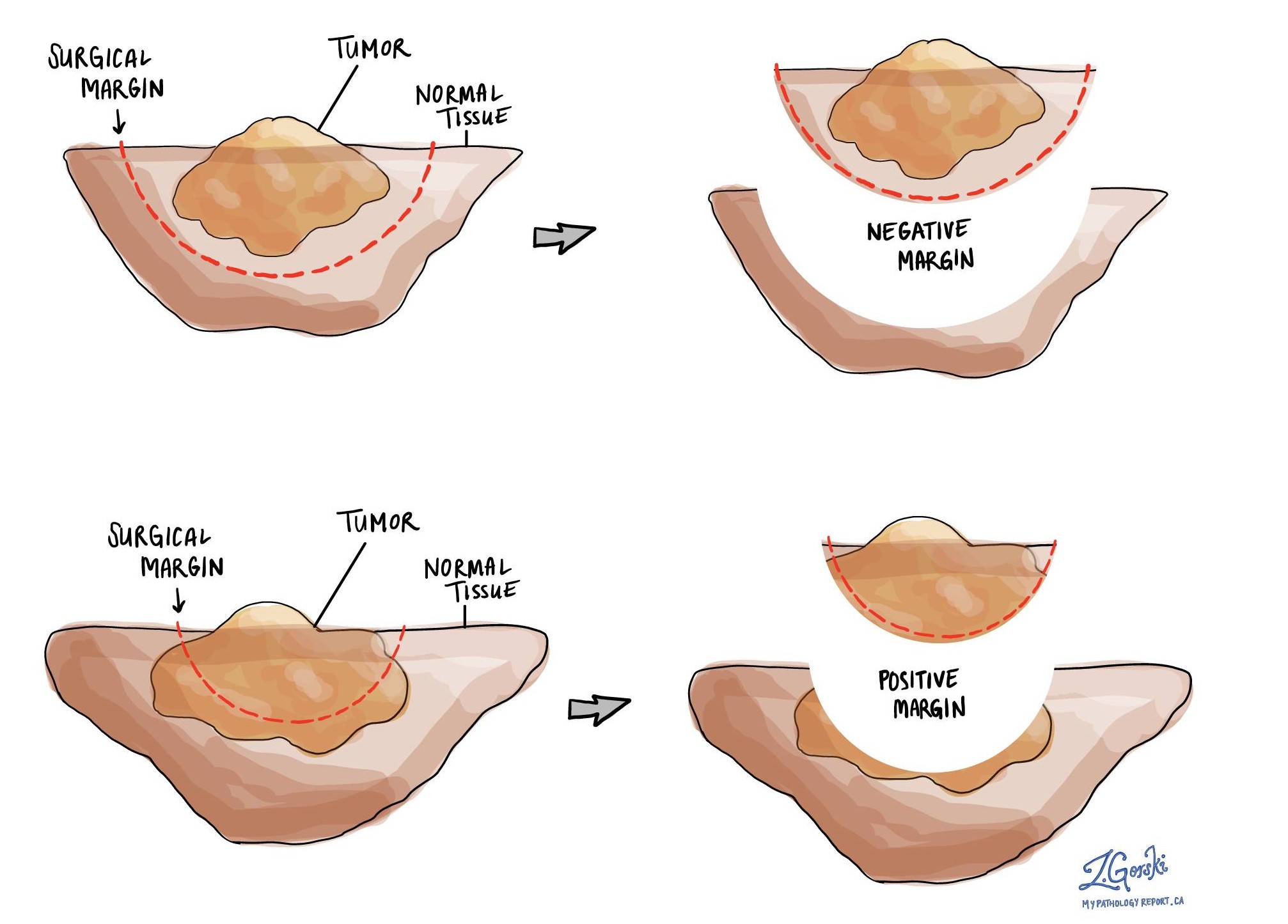

Margins

A margin is any tissue that has to be cut by the surgeon in order to remove the tumour from your body. For most testis specimens, the most important margin is the spermatic cord. When examining a seminoma, a margin is considered ‘negative’ when there are no cancer cells at the cut edge of the tissue. A margin is considered ‘positive’ when there is no distance between the cancer cells and the edge of the tissue that has been cut. A positive margin is associated with a higher risk that the tumour will come back (recur) in the same site after treatment.

Were lymph nodes examined and did any contain cancer cells?

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Although rare, the cancer cells in spermatocytic tumour can spread from the tumour to lymph nodes through small vessels called lymphatics. For this reason, lymph nodes are commonly removed and examined under a microscope to look for cancer cells. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to another part of the body such as a lymph node is called a metastasis.

Cancer cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour although lymph nodes far away from the tumour can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are only typically removed if they are enlarged and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancer cells in the lymph node.

If any lymph nodes were removed from your body, they will be examined under the microscope by a pathologist and the results of this examination will be described in your report. Most reports will include the total number of lymph nodes examined, where in the body the lymph nodes were found, and the number (if any) that contain cancer cells. If cancer cells were seen in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) will also be included.

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy is required.

What does it mean if a lymph node is described as positive?

Pathologists often use the term “positive” to describe a lymph node that contains cancer cells. For example, a lymph node that contains cancer cells may be called “positive for malignancy”.

What does it mean if a lymph node is described as negative?

Pathologists often use the term “negative” to describe a lymph node that does not contain any cancer cells. For example, a lymph node that does not contain cancer cells may be called “negative for malignancy”.

What is a tumour deposit?

A group of cancer cells inside of a lymph node is called a tumour deposit. If a tumour deposit is found, your pathologist will measure the deposit and the largest tumour deposit found may be described in your report.

What does extranodal extension (ENE) mean?

All lymph nodes are surrounded by a thin layer of tissue called a capsule. Cancer cells that have spread to a lymph node can break through the capsule and into the tissue surrounding the lymph node. This is called extranodal extension (ENE). Extranodal extension is important because it is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN).

How do pathologists determine the pathologic stage (pTMN) for spermatocytic tumour?

The pathologic stage for spermatocytic tumour is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system originally created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT) for spermatocytic tumour

Spermatocytic tumour is given a tumour stage between 1 and 4 based on the location of the tumour, the extent of tumour extension into surrounding tissues, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion.

- T1 – The tumour is only seen in the testis. It does not extend into any of the surrounding tissue.

- T2 – The tumour is only seen in the testis AND lymphovascular invasion is seen OR the tumour extends into the hilar soft tissue, epididymis, or tunica albuginea.

- T3 – The tumour extends into the spermatic cord.

- T4 – The tumour extends into the scrotum.

Nodal stage (pN) for spermatocytic tumour

Spermatocytic tumour is given a nodal stage of 0 to 3 based on the number of lymph nodes with tumour cells, the size of the largest lymph node with cancer cells, and the presence of extranodal extension.

- Nx – No lymph nodes were sent for pathologic examination.

- N0 – No cancer cells are seen in any lymph nodes examined.

- N1 – Cancer cells are seen inside no more than 5 lymph nodes and none of the lymph nodes are larger than 2 cm.

- N2 – Cancer cells are seen in more than 5 lymph nodes but none of the lymph nodes are over 5 cm OR extranodal extension is seen.

- N3 – Cancer cells are seen in a lymph node over 5 cm.