by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD

June 12, 2025

Urothelial carcinoma is a type of cancer. It develops from special cells called urothelial cells, which line the inside surface of the urinary tract. The urinary tract includes the bladder, ureters, kidneys, and urethra. Most urothelial carcinomas start in the bladder, making it the most common type of bladder cancer. Sometimes, this cancer can begin as a non-invasive type called urothelial carcinoma in situ, before becoming invasive.

Understanding the urinary tract

The urinary tract is the system that helps remove waste and extra fluid from the body through urine. It includes these parts:

-

Kidneys: Organs that filter blood to make urine.

-

Ureters: Tubes that carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder.

-

Bladder: A muscular sac that stores urine until you urinate.

-

Urethra: The tube that carries urine out of the body.

The inner lining of the urinary tract is composed of specialized cells called urothelial cells, which form a protective barrier known as the urothelium.

What causes urothelial carcinoma?

Several factors can increase a person’s chance of developing urothelial carcinoma.

Common risk factors include:

-

Smoking tobacco (the most important risk factor).

-

Exposure to certain chemicals, such as opium, benzidine-based dyes, aromatic amines, and arsenic.

-

Using herbal remedies containing aristolochic acid from Aristolochia plants.

-

Chronic bladder irritation from long-term catheter use, bladder stones, or infections like Schistosoma haematobium.

-

Previous treatments involving radiation to the pelvis or chemotherapy drugs like cyclophosphamide or chlornaphazine.

Genetic syndromes linked to urothelial carcinoma

Some inherited genetic conditions can also raise the risk of developing urothelial carcinoma:

-

Lynch syndrome: People with this condition are more likely to develop tumours in the upper urinary tract, such as in the kidneys or ureters.

-

Costello syndrome: People with this syndrome have a higher chance of developing bladder tumours.

Symptoms of urothelial carcinoma

Common symptoms of urothelial carcinoma include:

-

Blood in the urine, causing it to appear red, pink, or brown.

-

Pain or a burning sensation during urination.

-

Needing to urinate more frequently or urgently.

-

Pain in the abdomen or back, especially if a tumour blocks urine flow from the kidneys or ureters.

How does urothelial carcinoma spread?

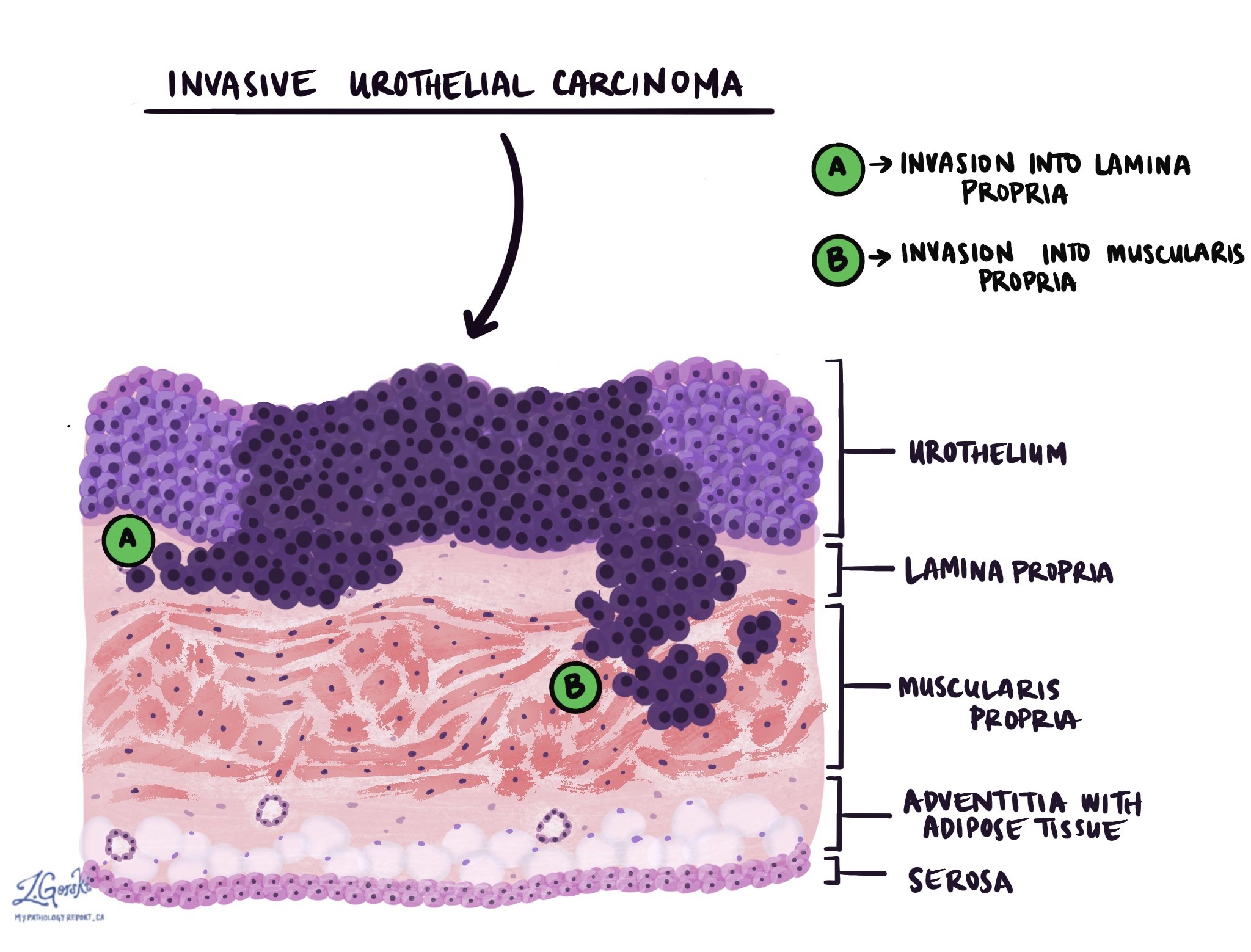

Urothelial carcinoma originates in the urothelium and can spread into the deeper layers of tissue beneath this lining. Pathologists describe this as invasion. These deeper layers include connective tissue called the lamina propria, muscle tissue called the muscularis propria, fatty tissue, and sometimes outer layers like the serosa. Your pathologist will look carefully to see how deeply the cancer cells have spread. This depth of invasion helps determine how serious the cancer is (the tumour stage) and helps guide your treatment.

How is urothelial carcinoma diagnosed?

Your doctor might use several tests to diagnose urothelial carcinoma:

-

Urine test (urine cytology): Looking at urine under a microscope to find cancer cells.

-

Biopsy: Removing a small piece of tissue from the bladder or urinary tract, often using a procedure called cystoscopy.

-

Surgery to remove the tumour, known as a transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT), for diagnosis and initial treatment.

-

For larger or invasive tumours, more extensive surgery may be needed to remove part or all of the affected organ.

Tumour grade

Pathologists classify urothelial carcinoma as low grade or high grade based on how the tumour cells look under a microscope:

-

Low-grade tumours: Cells look similar to normal urothelial cells. These tumours grow slowly and are less likely to invade or spread.

-

High-grade tumours: Cells look very abnormal, large, dark, and disorganized. Most urothelial carcinomas are high grade. These tumours grow more quickly and have a higher chance of spreading or coming back after treatment.

Squamous and glandular differentiation

Sometimes, the tumour cells in urothelial carcinoma can change and look like other types of cells:

-

Squamous differentiation: Tumour cells look similar to squamous cells (cells normally found in the skin). Up to 40% of tumours may show this change.

-

Glandular differentiation: Tumour cells form gland-like structures that resemble glands found in the colon.

Variants of urothelial carcinoma

Variants are types of urothelial carcinoma with unique microscopic patterns. Certain variants are more aggressive, increasing the likelihood of spreading. The most common variants of urothelial carcinoma are described in the sections below.

Micropapillary urothelial carcinoma

Tumour cells form tiny finger-like projections (“micropapillary”) found in open spaces called lacunae. This aggressive variant often spreads rapidly to lymph nodes and distant organs.

Nested urothelial carcinoma

Tumour cells form small groups (“nests”) closely resembling normal bladder structures, making diagnosis difficult in small biopsy samples.

Tubular and microcystic urothelial carcinoma

Tumour cells form small, rounded structures known as tubules or microcysts.

Large nested urothelial carcinoma

Similar to nested carcinoma but forms larger nests. This aggressive variant commonly spreads outside the bladder to lymph nodes and distant sites.

Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma

Tumour cells resemble immune cells called plasma cells. Cells do not stick together (“discohesive”), spreading aggressively to lymph nodes and other organs.

Sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma

Tumour cells resemble sarcoma, an aggressive cancer type that often spreads to lungs and bones. Some sarcomatoid tumours contain cells resembling bone, muscle, or cartilage (heterologous differentiation), indicating a poorer prognosis.

Lymphoepithelioma-like urothelial carcinoma

Tumour cells look very abnormal (“undifferentiated”) and are often surrounded by immune cells called lymphocytes.

Clear cell urothelial carcinoma

Tumour cells contain glycogen (a storage substance), giving a clear appearance under the microscope.

Poorly differentiated urothelial carcinoma

Tumour cells differ significantly from normal urothelial cells. Pathologists usually perform immunohistochemistry (special tests) to confirm the tumour’s origin.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells have entered small blood or lymph vessels, allowing the cancer to spread to lymph nodes or other body parts. Finding lymphovascular invasion increases the risk that the cancer may spread elsewhere.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small organs that help the body fight infection. Cancer cells can spread to lymph nodes through tiny vessels called lymphatic channels. During surgery, lymph nodes near the tumour are often removed and checked for cancer cells.

If cancer cells are found, the lymph nodes are called “positive.” If no cancer cells are present, the lymph nodes are called “negative.” The results help determine whether additional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiation, or immunotherapy, are needed.

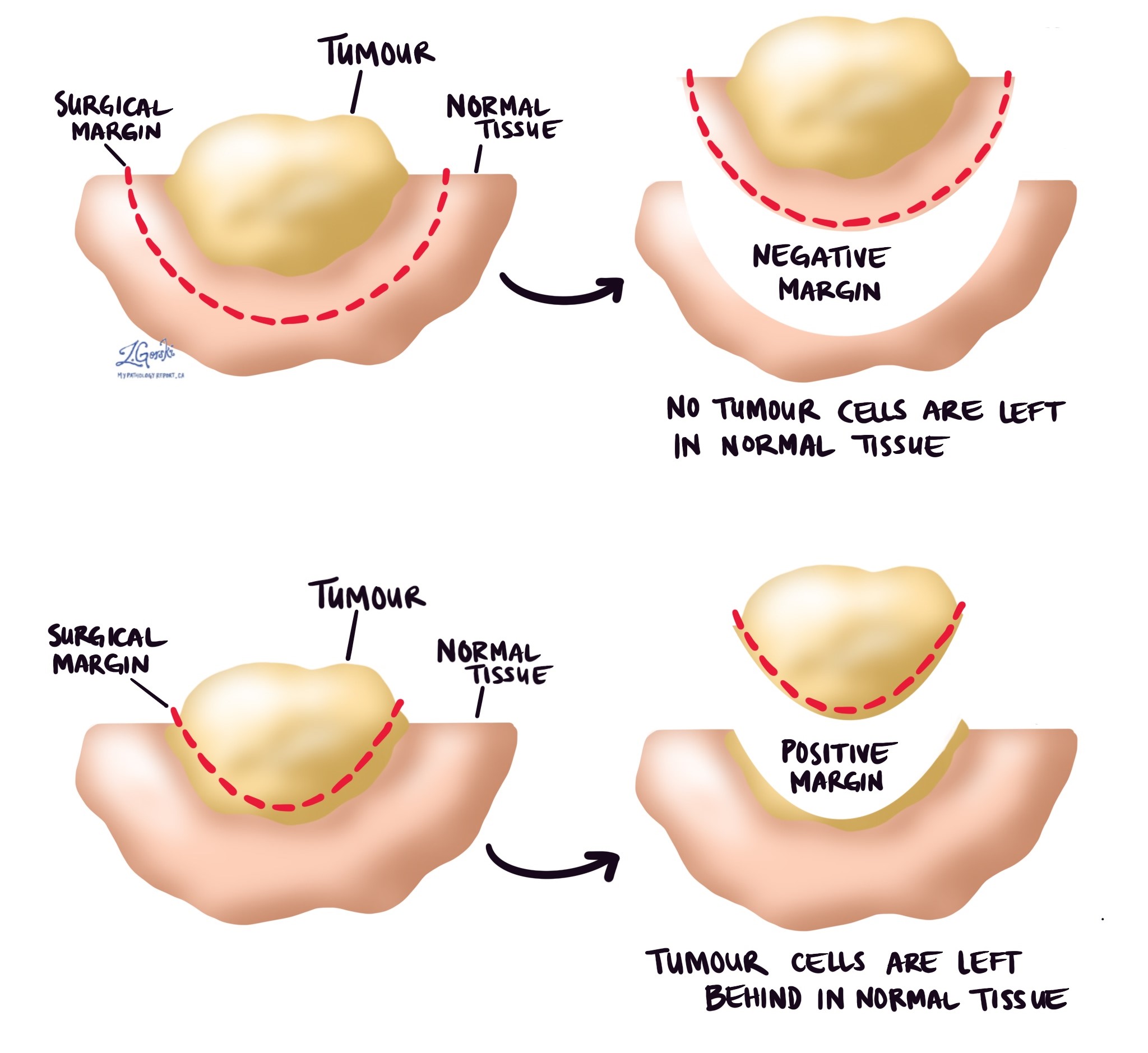

Margins

Margins refer to the edges of the tissue that a surgeon removes during cancer surgery. Pathologists carefully examine these edges under a microscope to check if any cancer cells remain.

-

Negative margin: No cancer cells found, meaning the tumour was likely completely removed.

-

Positive margin: Cancer cells are present at the edge, suggesting some cancer might still remain in the body, requiring further treatment.

Pathologic stage (TNM system)

Doctors use the TNM system to describe how advanced the cancer is. It includes the following parts:

Tumour stage (T):

-

T1: Tumour has grown into the connective tissue layer (lamina propria).

-

T2: Tumour has grown into the bladder muscle layer.

-

T3: Tumour has reached the fatty tissue around the bladder.

-

T4: Tumour has spread into nearby organs like the prostate, uterus, or pelvic wall.

Nodal stage (N):

-

N0: No cancer cells in lymph nodes.

-

N1: Cancer cells found in one pelvic lymph node.

-

N2: Cancer cells found in multiple pelvic lymph nodes.

-

N3: Cancer cells found in lymph nodes outside the pelvis (common iliac nodes).

-

NX: No lymph nodes examined.

A higher stage means the cancer is more advanced and often requires more extensive treatment.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What is the stage and grade of my tumour, and what does this mean for my treatment?

-

Do I need additional treatments after surgery?

-

What is my risk of the tumour returning or spreading?

-

How often should I have follow-up tests or check-ups?

-

Should I make lifestyle changes to reduce my risk of recurrence?

-

Should my family members be screened for this type of cancer?

-

What symptoms or signs should I look out for that might indicate the cancer has returned?