by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

January 22, 2026

Endometrial serous adenocarcinoma is an aggressive type of cancer that starts in the endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus. It is considered a high-grade tumour, meaning it has a higher chance of spreading beyond the uterus compared to some other types of endometrial cancer.

Unlike the more common type of endometrial cancer, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, which is often linked to excess estrogen, endometrial serous adenocarcinoma typically develops in people with low estrogen levels. It often arises in a background of thin or atrophic endometrium (the natural thinning of the uterine lining that occurs after menopause).

What are the symptoms of endometrial serous adenocarcinoma?

Endometrial serous adenocarcinoma often does not cause symptoms in its early stages, making it harder to detect early. When symptoms do appear, they may include:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, especially after menopause.

- Unusual vaginal discharge, which may be watery or blood-tinged.

- Pelvic pain or pressure.

- Unexplained weight loss or fatigue in advanced cases.

Because postmenopausal bleeding is not normal, it is important to see a doctor if you experience unexpected vaginal bleeding after menopause.

What causes endometrial serous adenocarcinoma?

Although the exact cause of endometrial serous adenocarcinoma is not fully understood, it is believed to be driven by genetic changes in endometrial cells rather than hormonal factors. Unlike the more common endometrioid adenocarcinoma, which is often linked to excess estrogen, serous carcinoma is typically not associated with estrogen stimulation.

Risk factors for developing this cancer include:

- Older age, particularly after menopause.

- A history of pelvic radiation therapy.

- African American race.

- Lynch syndrome or other inherited genetic conditions that increase cancer risk.

- A history of ovarian or breast cancer.

- Genetic mutations, particularly involving the p53 tumour suppressor gene.

Although these risk factors may increase the likelihood of developing endometrial serous adenocarcinoma, some people develop the cancer without any known risk factors.

How is this diagnosis made?

Endometrial serous carcinoma is diagnosed by combining clinical information, imaging studies, and microscopic examination of tissue. In some cases, additional tests, such as immunohistochemistry and molecular testing, are performed to confirm the diagnosis and guide treatment.

Imaging studies

Imaging tests such as pelvic ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI are often performed when a patient has abnormal uterine bleeding or other symptoms. These tests can show thickening of the uterine lining or a mass in the uterus, but imaging alone cannot determine the exact tumour type. Tissue examination is always required for a definitive diagnosis.

Tissue sampling (biopsy or surgery)

A diagnosis is usually made after examining tissue obtained from the uterus. This tissue may be collected in several ways, including an endometrial biopsy, dilation and curettage (D&C), or hysteroscopy, which uses a small camera to visualize the uterus and collect samples. If cancer is confirmed or strongly suspected, the uterus may later be removed surgically, allowing for a more complete examination.

Microscopic features

When examined under the microscope, endometrial serous carcinoma has distinctive features that help pathologists recognize it.

The tumour often grows in papillary (finger-like), gland-forming, or solid patterns. The glands are typically irregular and slit-like rather than round. In some areas, the tumour may grow in solid sheets without forming glands, which reflects its aggressive nature.

The cancer cells show marked nuclear atypia, with nuclei that are large, irregular, and vary greatly in size and shape. Prominent nucleoli and frequent mitotic figures (dividing cells) are common, indicating rapid tumour growth. Multinucleated tumour cells and psammoma bodies (small round calcium deposits) may also be present.

A unique and important feature is serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma (SEIC). In SEIC, highly abnormal serous carcinoma cells replace the normal endometrial surface lining without obvious invasion into deeper tissues. Despite appearing “non-invasive,” SEIC can still spread beyond the uterus and is treated as a high-risk condition.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers are tests performed on tumour tissue to understand better how the cancer behaves and which treatments may be most effective. These tests commonly include immunohistochemistry and, in selected cases, molecular testing.

p53

Almost all endometrial serous carcinomas show an abnormal p53 result. This reflects a mutation in the TP53 gene, which normally helps control cell growth. Abnormal p53 staining (also called aberrant or mutant-type staining) strongly supports the diagnosis of serous carcinoma and indicates an aggressive tumour biology.

p16

p16 is typically strongly and diffusely positive in endometrial serous carcinoma. This staining pattern helps distinguish serous carcinoma from other types of endometrial cancer, especially high-grade endometrioid carcinoma.

ER and PR

Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression is variable in serous carcinoma and is often weak or absent. Loss of ER and PR expression supports a diagnosis of serous carcinoma rather than endometrioid carcinoma, which is usually strongly hormone-receptor positive.

HER2 (ERBB2)

Some endometrial serous carcinomas show HER2 overexpression or gene amplification. HER2 testing is usually performed using immunohistochemistry, and sometimes confirmed with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Tumours that are HER2-positive may benefit from targeted therapy with trastuzumab, which is added to standard chemotherapy in advanced or recurrent disease.

Mismatch repair proteins (MMR)

Mismatch repair proteins help repair DNA damage in normal cells. The four most commonly tested proteins are MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6. Testing is performed using immunohistochemistry and reported as either retained expression (normal) or loss of expression (abnormal).

Most endometrial serous carcinomas are MMR-proficient, meaning all four proteins are retained. However, when MMR deficiency is identified, it is clinically important because these tumours may respond well to immunotherapy. MMR testing is also used to screen for Lynch syndrome, a hereditary condition associated with an increased risk of several cancers, including endometrial cancer.

Molecular testing

In selected cases, next-generation sequencing (NGS) may be performed to look for genetic changes that provide prognostic or therapeutic information. Not all tumours undergo molecular testing, and the genes tested vary by institution.

- Mutations in TP53 are present in nearly all serous carcinomas and drive aggressive tumour behaviour.

- POLE mutations are rare in serous carcinoma, but when present, they are associated with an excellent prognosis and may influence treatment decisions.

- Mutations in PIK3CA or KRAS can occur in some cases and may contribute to tumour growth, although targeted treatments are still under investigation.

- PTEN mutations are uncommon in pure serous carcinoma; when identified, they may suggest a mixed tumour with endometrioid features.

Myometrial invasion

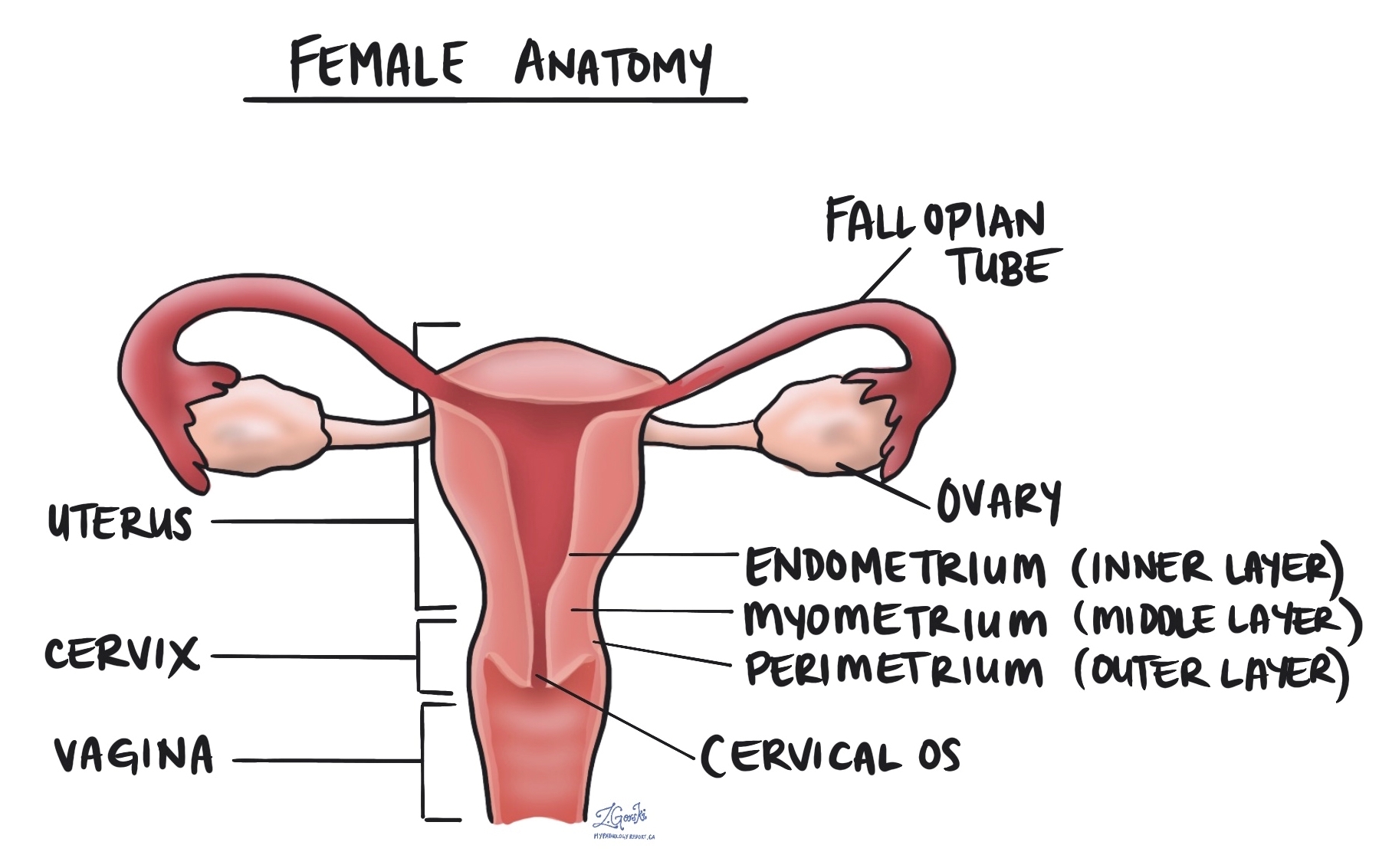

The myometrium is the thick muscular layer of the uterus. Myometrial invasion occurs when the cancer spreads from the inner lining of the uterus (the endometrium) into the myometrium. The depth of myometrial invasion is important because the deeper the tumour invades, the higher the risk of spreading to other parts of the body.

Most pathology reports for endometrial serous adenocarcinoma will describe the amount of myometrial invasion in millimetres and as a percentage of the total myometrial thickness. This information is used to stage the tumour and to plan treatment.

Cervical stromal invasion

Cervical stromal invasion means that the cancer has spread from the body of the uterus into the cervix, which is the lower part of the uterus that connects to the vagina. This type of invasion indicates a more advanced stage of cancer and may influence treatment decisions, such as the need for more extensive surgery or radiation therapy.

Invasion of surrounding organs or tissues

The uterus is closely connected to several other organs and tissues, such as the ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina, bladder, and rectum. The term “adnexa” refers to the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and ligaments directly linked to the uterus. A tumour can spread into these organs or tissues as it grows. In such cases, some parts of these organs or tissues may have to be removed along with the uterus. A pathologist will thoroughly examine these organs or tissues for tumour cells, and the findings will be detailed in your pathology report. Tumour cells in other organs or tissues are significant, as they raise the pathologic tumour stage and are linked with a poorer prognosis.

Lymphatic and vascular invasion

Lymphatic invasion occurs when cancer cells enter the lymphatic system, a network of vessels that helps fight infection. Vascular invasion refers to cancer cells entering the blood vessels. Both lymphatic and vascular invasion are important because they indicate that the cancer is more likely to spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body, including lymph nodes and distant organs. These findings are often included in a pathology report to help guide treatment decisions.

Margins

A margin refers to the edge of the tissue removed during surgery, such as a hysterectomy. After surgery, pathologists examine the tissue margins under a microscope to detect any remaining cancer cells. In the case of endometrial serous adenocarcinoma, several specific margins are carefully evaluated:

- Cervical margin: This is the edge where the uterus meets the cervix. Pathologists examine this margin to see if the cancer has spread into or beyond the cervix.

- Vaginal cuff margin: If the top portion of the vagina is removed along with the uterus, the pathologist will check the vaginal cuff margin to ensure no cancer cells are present at the surgical edge.

- Parametrial margin: This margin includes the tissue around the uterus, including ligaments and connective tissue. It is examined to see if cancer has spread into these areas.

- Peritoneal margin: If the peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity) is removed, it will be examined to check for cancer cells in this area.

If any of these margins contain cancer cells, it is referred to as a positive margin, which may mean some tumour cells were left behind after surgery. A negative margin means no cancer cells were found at the edges, suggesting the tumour was removed entirely. Clear margins are important for reducing the risk of the cancer returning, and positive margins may lead to recommendations for additional treatments, such as radiation therapy.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped structures that are part of the lymphatic system, which helps the body fight infection and remove waste. Lymph fluid travels through lymphatic vessels, and lymph nodes act as filters that can trap bacteria, viruses, and cancer cells. Lymph nodes are found throughout the body, including the pelvis and abdomen, which are common drainage areas for the uterus.

In endometrial serous carcinoma, lymph nodes are carefully examined because this type of cancer has a higher risk of spreading beyond the uterus. During surgery, lymph nodes from the pelvis and sometimes the abdomen may be removed and sent to a pathologist. Each lymph node is examined under the microscope to look for metastatic cancer, meaning cancer cells that have spread from the uterus.

The lymph node findings are important because they help determine the pathologic stage, guide treatment decisions, and provide prognostic information. When cancer is found in lymph nodes, additional treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy are more likely to be recommended.

Isolated tumour cells (ITCs)

Isolated tumour cells are very small clusters of cancer cells measuring 0.2 mm or less found in a lymph node. These tiny deposits may only be visible with special stains, such as immunohistochemistry.

When isolated tumour cells are the only cancer cells found in the lymph nodes, the nodal stage is usually reported as pN0(i+). ITCs have less prognostic impact than larger deposits, but they are still documented because they indicate early lymphatic spread.

Micrometastasis

A micrometastasis is a group of cancer cells measuring more than 0.2 mm but no more than 2 mm within a lymph node.

If micrometastases are present and no larger deposits are identified, the nodal stage is reported as pN1mi. Micrometastases indicate a higher risk of recurrence than isolated tumour cells and may influence treatment decisions.

Macrometastasis

A macrometastasis is a deposit of cancer cells measuring more than 2 mm in a lymph node.

Macrometastases are associated with a higher risk of recurrence and spread and are usually associated with a pN1 nodal stage. Their presence often leads to recommendations for systemic therapy, such as chemotherapy, and sometimes radiation therapy.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

The pathologic stage for endometrial serous adenocarcinoma is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the submitted tissue and assign each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT) for endometrial serous adenocarcinoma

Endometrial serous adenocarcinoma is given a tumour stage between T1 and T4 based on the depth of myometrial invasion and growth of the tumour outside of the uterus.

- T1 – The tumour only involves the uterus.

- T2 – The tumour has grown to involve the cervical stroma.

- T3 – The tumour has grown through the wall of the uterus and is now on the outer surface of the uterus, OR it has grown to involve the fallopian tubes or ovaries.

- T4 – The tumour has grown directly into the bladder or the colon.

Nodal stage (pN) for endometrial serous adenocarcinoma

Based on the examination of pelvic and abdominal lymph nodes, endometrial serous carcinoma is assigned a nodal stage of N0-N2.

- N0 – No tumour cells were found in any lymph nodes examined.

- N1mi – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node from the pelvis, but the area with cancer cells was not larger than 2 millimetres (only isolated cancer cells or micrometastasis).

- N1a – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node from the pelvis, and the area with cancer cells was greater than 2 millimetres (macrometastasis).

- N2mi – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node outside the pelvis, but the area with cancer cells was not larger than 2 millimetres (only isolated cancer cells or micrometastasis).

- N2a – Tumour cells were found in at least one lymph node outside the pelvis, and the area with cancer cells was greater than 2 millimetres (macrometastasis).

- NX – No lymph nodes were sent for examination.

FIGO stage

The FIGO staging system, developed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, is a standardized method for classifying endometrial cancers based on the extent of their spread. This system is important because it helps doctors determine the extent of the cancer, plan appropriate treatment, and estimate the prognosis (the likely disease outcome).

- Stage I: The cancer is confined to the uterus.

- IA: The cancer is limited to the endometrium or has invaded less than halfway into the myometrium. Stage IA cancers have an excellent prognosis, with a high likelihood of being successfully treated through surgery alone.

- IB: The cancer has invaded more than halfway into the myometrium. Although Stage IB is more advanced than Stage IA, it generally has a good prognosis, especially if treated promptly.

- Stage II: The cancer has spread from the uterus to the cervix but has not gone beyond the uterus. Stage II cancers are more likely to require additional treatments, such as radiation or chemotherapy, but many patients still have a favourable outcome with appropriate treatment.

- Stage III: The cancer has spread beyond the uterus but is still within the pelvis. Stage III cancers are more advanced and often require a combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. The prognosis is more guarded, but treatment can still be effective in many cases.

- IIIA: The cancer has spread to the outer surface of the uterus or to nearby tissues.

- IIIB: The cancer has spread to the vagina or the pelvic wall.

- IIIC: The cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

- Stage IV: The cancer has spread to distant organs, such as the bladder, bowel, or lungs. Stage IV cancers are the most advanced and carry a more serious prognosis. Treatment at this stage is usually focused on managing symptoms and slowing disease progression.

- IVA: The cancer has spread to nearby organs such as the bladder or rectum.

- IVB: The cancer has spread to distant organs, such as the lungs or liver.

What is the prognosis for a person diagnosed with endometrial serous adenocarcinoma?

The prognosis for endometrial serous adenocarcinoma depends on how far the cancer has spread at the time of diagnosis.

- If the cancer is confined to the uterus, the prognosis is better, and patients may be cured with surgery alone.

- If the cancer has spread outside the uterus, including cases with serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma (SEIC) or minimal invasion, the prognosis is poorer.

Because endometrial serous carcinoma is aggressive, it is more likely to spread to other parts of the body compared to other types of endometrial cancer. Many recurrences occur outside the pelvis.

HER2 (ERBB2) overexpression is a key prognostic and therapeutic factor. This protein is found in more than 30% of serous carcinomas. In advanced or recurrent cases, patients with HER2-positive tumours may benefit from trastuzumab (Herceptin), a targeted therapy that is added to standard chemotherapy (carboplatin and paclitaxel).

Because of its aggressive nature, most patients with endometrial serous adenocarcinoma receive a combination of surgery (hysterectomy), radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Some cases may also be treated with targeted therapy if specific molecular changes are present.