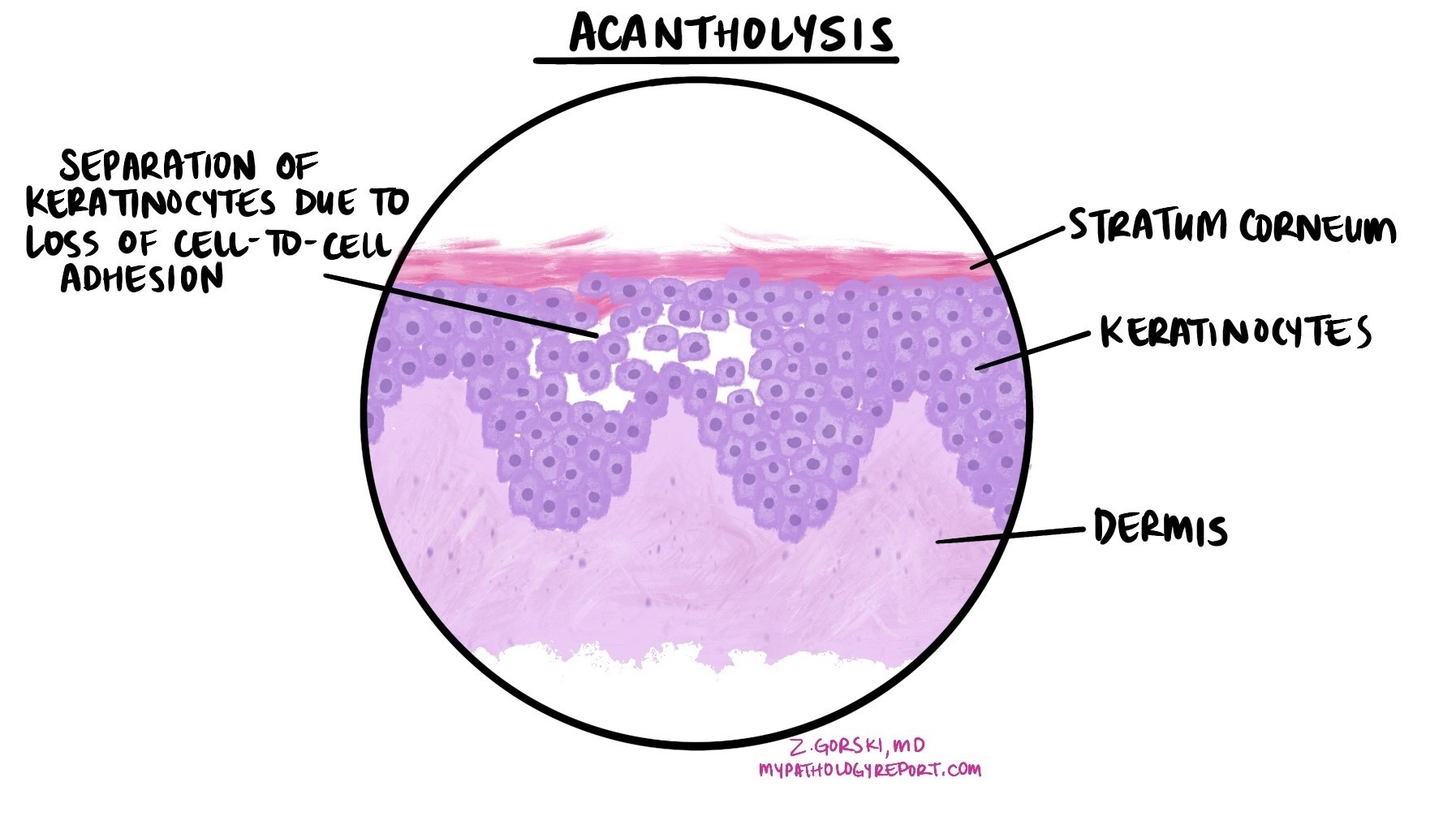

Acantholysis is a term pathologists use to describe the loss of connections between skin cells in the outermost layer of the skin, known as the epidermis. When these connections break down, the cells separate from each other, creating spaces within the epidermis. This process can lead to the formation of blisters or erosions on the skin or mucous membranes.

Where does acantholysis occur?

Acantholysis happens within the epidermis, which is normally made up of tightly connected cells called keratinocytes. These cells are joined together by specialized structures known as desmosomes. In acantholysis, the desmosomes are damaged or destroyed, causing the keratinocytes to lose their attachment to one another. This separation can occur in different layers of the epidermis depending on the underlying cause.

What causes acantholysis?

Acantholysis can occur in a variety of conditions, including:

-

Autoimmune blistering diseases: In autoimmune conditions such as pemphigus, the immune system produces antibodies that attack the desmosomes, leading to cell separation and blister formation.

-

Viral infections: Some viral infections, such as herpes simplex or varicella (chickenpox), can damage the desmosomes or surrounding cell structures, resulting in acantholysis.

-

Genetic disorders: Rare inherited conditions, like Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease, can affect the proteins that help hold skin cells together, making acantholysis more likely.

-

Other skin conditions: Certain inflammatory or reactive skin diseases can cause localized areas of acantholysis.

What does acantholysis look like under the microscope?

Pathologists identify acantholysis by examining a skin or mucosal biopsy under a microscope. In affected areas, the keratinocytes appear separated from one another, with small gaps between them. These spaces can be filled with fluid, leading to blister formation. The report may also describe the level within the epidermis where the separation occurs, as this detail can help determine the underlying cause.

Why is acantholysis important?

The presence of acantholysis in a biopsy is an important clue for diagnosing certain skin diseases, particularly autoimmune blistering disorders like pemphigus. Identifying the pattern and location of acantholysis can help your doctor choose the right additional tests—such as immunofluorescence—to confirm the diagnosis and guide treatment.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What is causing the acantholysis in my biopsy?

-

Does this finding mean I have an autoimmune blistering disease like pemphigus?

-

Are additional tests needed to confirm the diagnosis?

-

How will this finding affect my treatment plan and prognosis?