Acanthosis is a word pathologists use to describe tissue that has become thicker than normal because of an increased number of squamous cells. Squamous cells are flat, protective cells that form the surface lining of many parts of the body, including the skin, mouth, throat, esophagus, large airways, anal canal, and cervix.

When these cells multiply and form extra layers, the tissue becomes thicker—a change known as acanthosis. This is usually a benign (non-cancerous) process, although it may occur in a variety of conditions.

What causes acanthosis?

Acanthosis can develop in response to chronic irritation or inflammation. It is the body’s way of strengthening the surface layer to protect itself from further injury.

Common causes include:

-

Skin conditions, such as psoriasis or eczema.

-

Chronic infections, trauma, or rubbing (friction).

-

Inflammation in mucosal areas like the mouth, cervix, or anal canal.

-

Reactive changes from long-term exposure to smoke, acid reflux, or infection.

-

In some cases, acanthosis can also be seen on the surface of certain tumours, including squamous cell carcinoma (a type of cancer made up of squamous cells).

Because it can occur alongside both benign and malignant conditions, the cause of acanthosis depends on the surrounding tissue and the clinical context.

Is acanthosis serious?

On its own, acanthosis is usually not serious. It is often a protective response to inflammation or irritation and does not mean cancer is present. However, in some situations, especially if the thickened tissue appears abnormal or is associated with a mass or ulcer, additional testing may be recommended to rule out precancerous or cancerous changes.

Your doctor will consider your overall symptoms, medical history, and location of the tissue when deciding if any follow-up is needed.

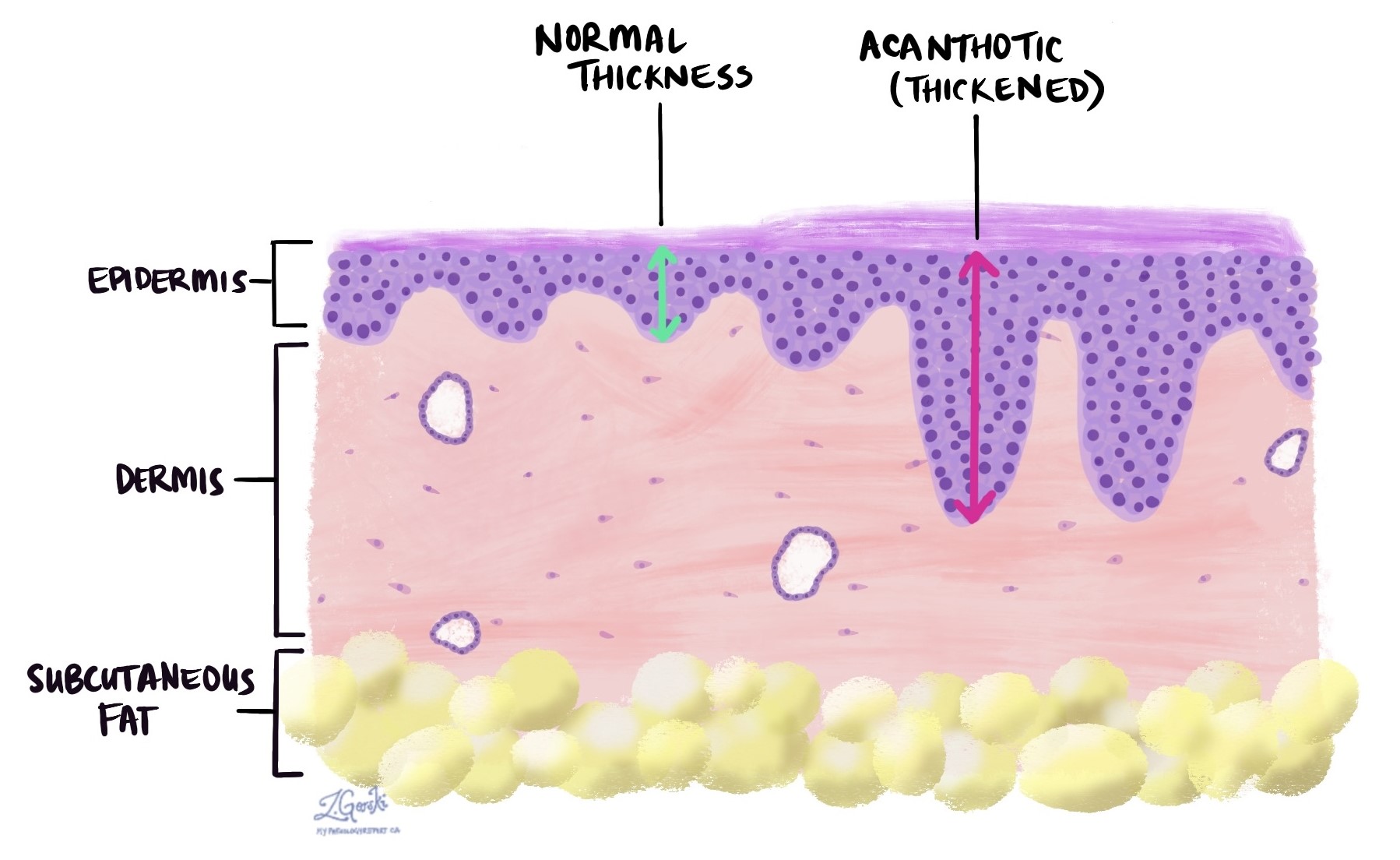

What does acanthosis look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, acanthosis appears as a thickening of the squamous epithelium, the layer of flat cells covering the surface of the tissue. This thickened layer is due to an increased number of squamous cells, especially in the middle layer. The cells may appear normal in shape and well-organized, which helps the pathologist recognize that the thickening is non-cancerous.

In some cases, acanthosis may be accompanied by other changes such as inflammation or keratosis (extra surface keratin).

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What caused the acanthosis in my report?

-

Is this a reactive or benign change, or could it be related to another condition?

-

Do I need any follow-up tests or monitoring?

-

Was there any sign of dysplasia (precancerous change) or cancer?