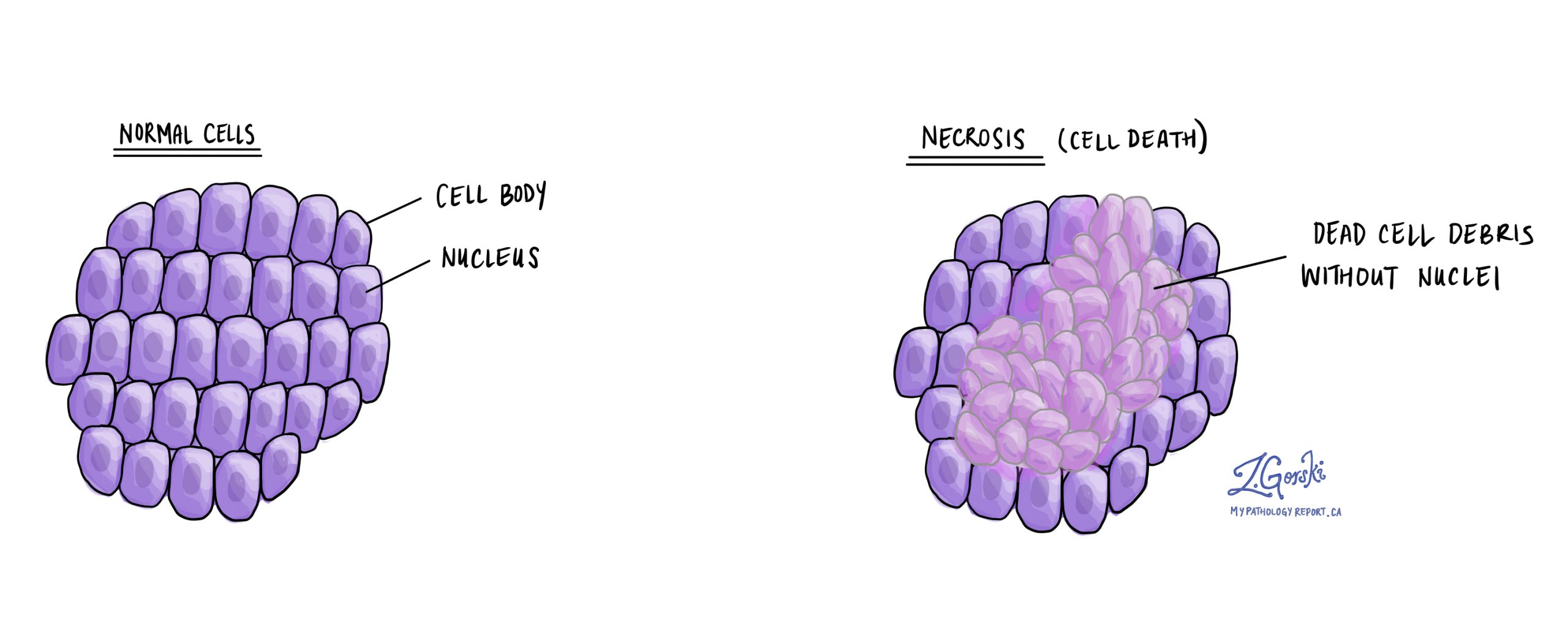

Necrosis is a medical term used by pathologists to describe cells or tissues that have died unexpectedly or prematurely within the body. Necrosis typically occurs because cells have been damaged or deprived of blood supply and nutrients. Unlike apoptosis, which is the body’s natural way of removing old or unneeded cells, necrosis happens suddenly, often due to injury or stress, causing inflammation and damage to nearby healthy tissue. Necrosis can happen in many situations, including in cancers, where tumour cells grow faster than their blood supply, causing areas of tissue to die.

What causes necrosis?

Necrosis can be caused by various factors, including:

-

Lack of blood supply (ischemia): When blood flow is interrupted, cells lose access to oxygen and nutrients, resulting in tissue death. Examples include heart attacks and strokes.

-

Cancer: Fast-growing cancers can experience necrosis when the tumour cells outgrow their blood supply, causing parts of the tumour to die.

-

Infections: Certain bacterial or viral infections can damage tissues and cause necrosis.

-

Trauma or injury: Physical damage such as wounds or burns can directly kill cells, leading to necrosis.

-

Toxins and chemicals: Exposure to harmful substances or poisons may lead to cell death.

-

Immune system reactions: In autoimmune diseases, the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissues, causing cell death and necrosis.

Does necrosis mean cancer?

No. Necrosis itself does not mean cancer. It simply indicates that cells or tissues have died unexpectedly. Necrosis can occur in both noncancerous (benign) and cancerous (malignant) tissues. However, when pathologists see necrosis in a tumour, it may provide useful information about the tumour’s behavior and how quickly it’s growing.

What does it mean if necrosis is seen in a tumor?

When necrosis is present in a tumour, it often indicates that the tumour is growing rapidly. Tumours may grow faster than their blood supply can support, leading to areas of the tumour becoming starved of oxygen and nutrients, and ultimately dying. Seeing necrosis in a tumour is important because it may suggest a more aggressive cancer that requires more intensive treatment. Pathologists carefully document the presence and extent of necrosis, as this information helps doctors decide on the best treatment plan.

What are the types of necrosis?

Pathologists identify several common types of necrosis, each reflecting different underlying causes and patterns of tissue injury:

-

Coagulative necrosis: Often due to interrupted blood supply (ischemia), frequently seen after a heart attack.

-

Liquefactive necrosis: Typically occurs following bacterial infections or in the brain after a stroke, where tissue breaks down into a liquid-like state.

-

Caseous necrosis: Associated with infections like tuberculosis, tissue appears crumbly and cheese-like.

-

Fat necrosis: Happens when fat tissue is damaged, such as following injury or in conditions affecting the pancreas.

-

Fibrinoid necrosis: Found primarily in immune reactions affecting blood vessel walls, causing fibrin-like material to build up in vessel walls.

What does necrosis look like under a microscope?

Under the microscope, necrotic tissue looks noticeably different from healthy, living tissue. Necrotic cells typically lose their normal structure, appearing swollen, fragmented, or disorganized. The cells lose their distinct nuclei (the part containing DNA) or have nuclei that appear dark and condensed. Often, pathologists see inflammatory cells around necrotic tissue because the body’s immune system attempts to clear away the damaged area. The specific appearance can vary depending on the type of necrosis, but in all cases, the presence of necrosis helps pathologists understand what caused the tissue damage and provides valuable information to guide patient care.