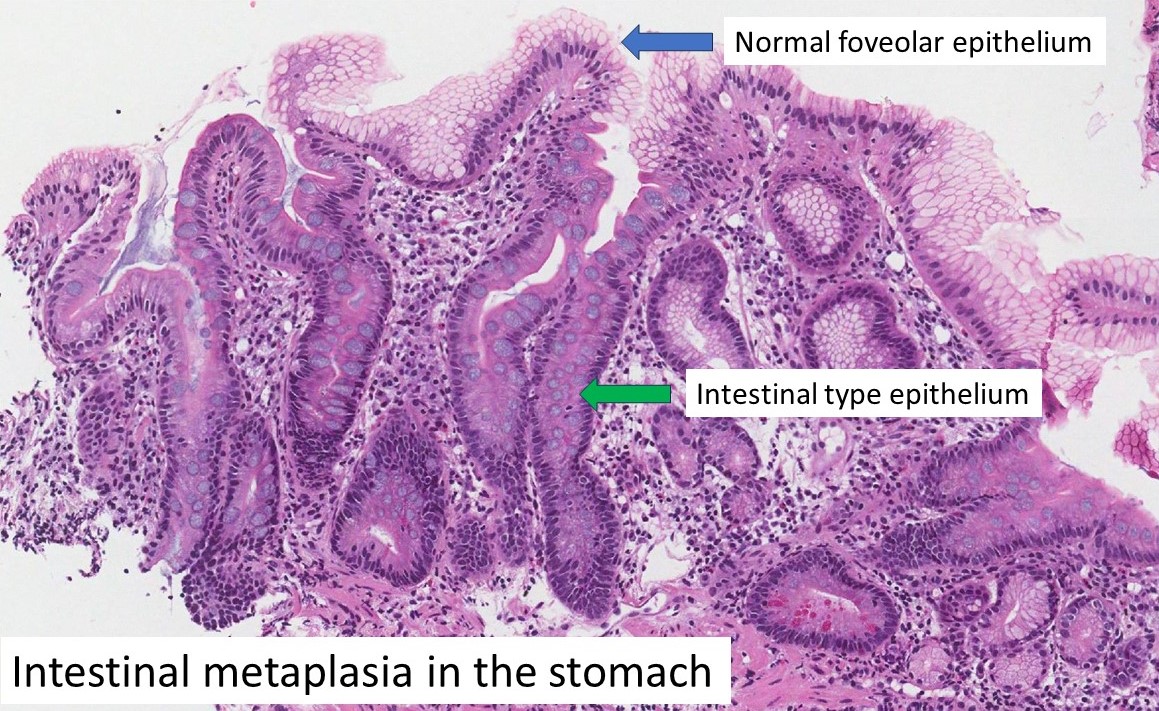

Intestinal metaplasia is a change that occurs when the cells that normally line an organ are replaced by cells that resemble those found in the intestine. The word metaplasia means that one type of normal cell has been replaced by another type of normal cell that is not usually found in that location. In intestinal metaplasia, the new cells resemble the special cells of the intestine, which are adapted to absorb nutrients and produce mucus.

Where does intestinal metaplasia occur?

Intestinal metaplasia most often occurs in the stomach and the esophagus.

-

In the stomach, intestinal metaplasia can develop after long-standing inflammation, often caused by infection with Helicobacter pylori (a type of bacteria that lives in the stomach lining). This condition is called Helicobacter gastritis.

-

In the esophagus, intestinal metaplasia is part of a condition called Barrett’s esophagus, which can occur when the lining of the esophagus is repeatedly exposed to stomach acid during acid reflux.

Why does intestinal metaplasia happen?

Intestinal metaplasia usually develops as a response to chronic irritation or injury.

Common causes include:

-

Chronic infection: For example, H. pylori infection in the stomach.

-

Long-term acid reflux: This can damage the lining of the esophagus and lead to Barrett’s esophagus.

-

Chronic inflammation: Long-lasting inflammation can encourage cells to change into a type better suited to the environment.

This change is thought to be the body’s way of protecting itself, but it also makes the affected tissue behave differently than normal.

Is intestinal metaplasia cancer?

No. Intestinal metaplasia is not cancer. It is considered a precancerous change, which means it is not harmful by itself but it can increase the risk of cancer developing in the future if the underlying cause is not treated. Most people with intestinal metaplasia will never develop cancer, but doctors may recommend follow-up to monitor the area for further changes.

Why is intestinal metaplasia important in a pathology report?

When intestinal metaplasia is described in a pathology report, it tells your doctor that the normal lining of your organ has been replaced by intestinal-type cells. This finding is important because it may:

-

Point to an underlying cause such as H. pylori infection or chronic acid reflux.

-

Identify a higher risk of cancer developing in the affected area.

-

Influence your doctor’s decisions about treatment, follow-up, or monitoring with repeat biopsies.

What does intestinal metaplasia look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, pathologists see cells that are normally found in the intestine, such as goblet cells. Goblet cells are specialized cells that produce mucus. They look different from the usual cells of the stomach or esophagus, making it possible for pathologists to identify intestinal metaplasia.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

Where was intestinal metaplasia found in my biopsy?

-

What caused this change in my case?

-

Does this increase my risk of developing cancer?

-

Do I need treatment for the underlying cause, such as H. pylori infection or acid reflux?

-

How often should I have follow-up testing or endoscopy to monitor this change?