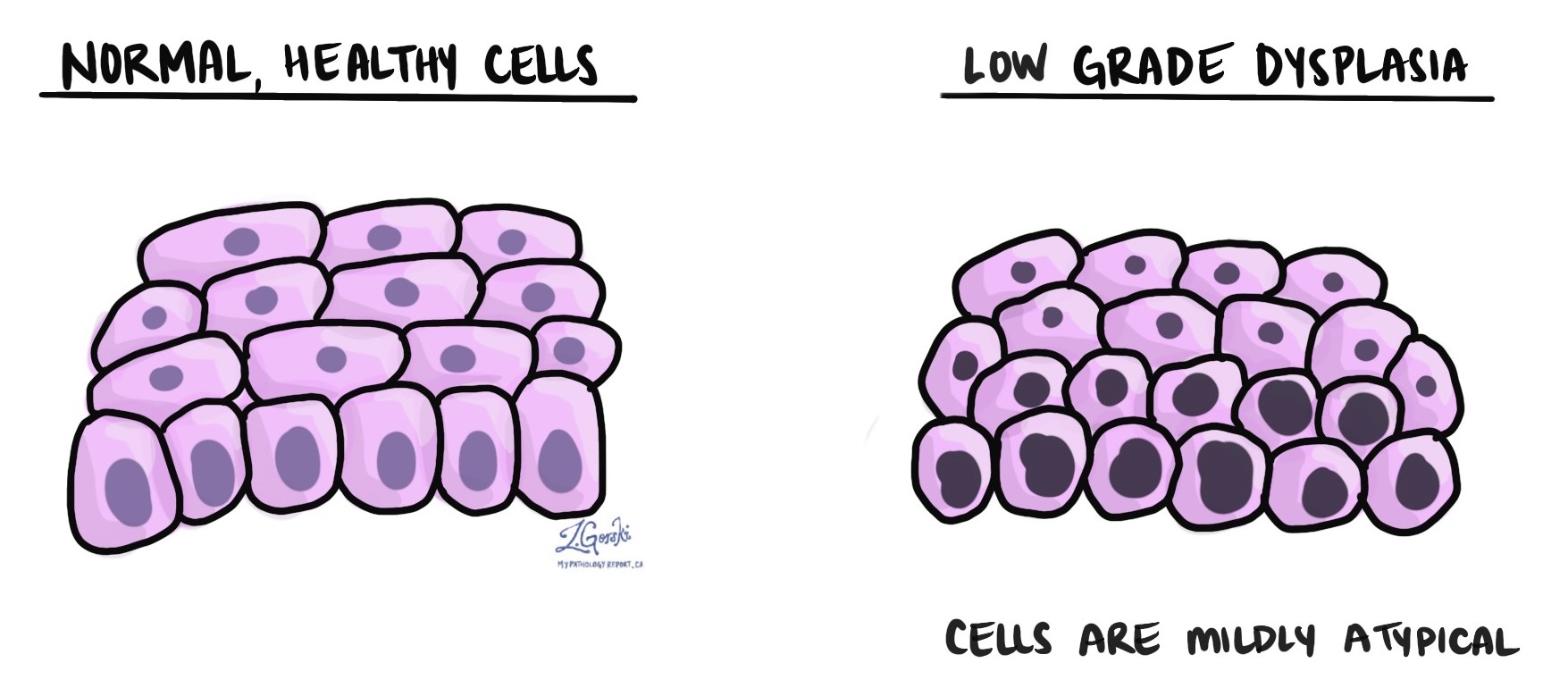

Low grade dysplasia is a precancerous condition characterized by mildly abnormal cells that grow differently from normal, healthy cells. When examined under a microscope, these abnormal cells still closely resemble normal cells, which is why the condition is termed “low grade.” This is in contrast to high grade dysplasia, where the cells appear more abnormal and have a greater risk of turning into cancer.

Does low grade dysplasia mean cancer?

No, low grade dysplasia is not cancer. It is considered precancerous, meaning that while the abnormal cells have the potential to become cancerous over time, most cases do not progress to cancer. Because there is some risk of progression, doctors typically recommend regular monitoring through screenings and biopsies to detect any changes early, especially progression to high grade dysplasia or cancer.

What causes low grade dysplasia?

The cause of low grade dysplasia depends on where in the body it occurs.

Common causes include:

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) infections in the cervix, penis, or anus; tobacco use in the mouth, throat, or esophagus

- Chronic acid reflux (GERD) leading to Barrett’s esophagus.

- Helicobacter pylori infection in the stomach

- Dietary or inflammatory factors in the colon, particularly with long-term inflammatory bowel disease.

Identifying the cause helps guide treatment and prevention strategies.

How long does it take for low grade dysplasia to turn into cancer?

Low grade dysplasia typically progresses very slowly, often taking many years or even decades, and in most cases, it does not progress to cancer at all. The timeline can vary based on the location and underlying cause. For instance, low grade cervical dysplasia due to HPV (also called LSIL) can remain stable for over 10 years without progressing, while dysplasia related to chronic acid reflux in the esophagus may progress slowly over several years. Regular monitoring helps catch changes early, significantly reducing the risk of developing cancer.

Can low grade dysplasia go away on its own?

Yes, low grade dysplasia can sometimes resolve on its own, especially if the underlying cause is addressed or treated. For example, low grade dysplasia caused by HPV often clears without treatment as the immune system resolves the infection. Similarly, treating underlying issues like acid reflux or quitting smoking can reduce or eliminate dysplasia in affected tissues.

Does low grade dysplasia need to be treated?

Low grade dysplasia often does not require immediate treatment beyond addressing the underlying cause and regular monitoring. Lifestyle changes, medical therapies for underlying infections or inflammation, and routine follow-up screenings are often sufficient. However, if dysplasia persists, progresses, or occurs in an area where cancer risk is higher, a doctor may recommend removing the abnormal tissue or additional interventions to prevent progression.