In pathology, rhabdoid describes tumour cells resembling immature muscle cells called rhabdomyoblasts. Although these cells resemble developing muscle cells, they are not actually muscle-related, and tumours with rhabdoid cells typically do not arise from muscle tissue. Instead, “rhabdoid” refers specifically to their appearance under a microscope. Tumours containing rhabdoid cells tend to behave aggressively and may require more intensive treatment.

What types of tumours have rhabdoid cells?

Tumours containing rhabdoid cells can occur in various body parts and are typically more aggressive. Some common examples include:

-

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumour (AT/RT): A highly aggressive brain tumour most frequently seen in young children.

-

Malignant rhabdoid tumour (MRT): A rare and aggressive cancer that can occur in almost any part of the body, including the kidneys, liver, skin, and soft tissues. Originally, these tumours were described primarily in the kidney.

-

Rhabdoid tumour of the kidney: A specific type of malignant rhabdoid tumour occurring in children’s kidneys, often aggressive and challenging to treat.

-

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour (MPNST) with rhabdoid features (also called Triton tumour): A rare type of cancer that arises from nerve sheath cells and includes rhabdoid cells, indicating a particularly aggressive behaviour.

In addition, rhabdoid cells may occasionally be seen in other aggressive cancers, including certain carcinomas and sarcomas.

What do rhabdoid cells look like under a microscope?

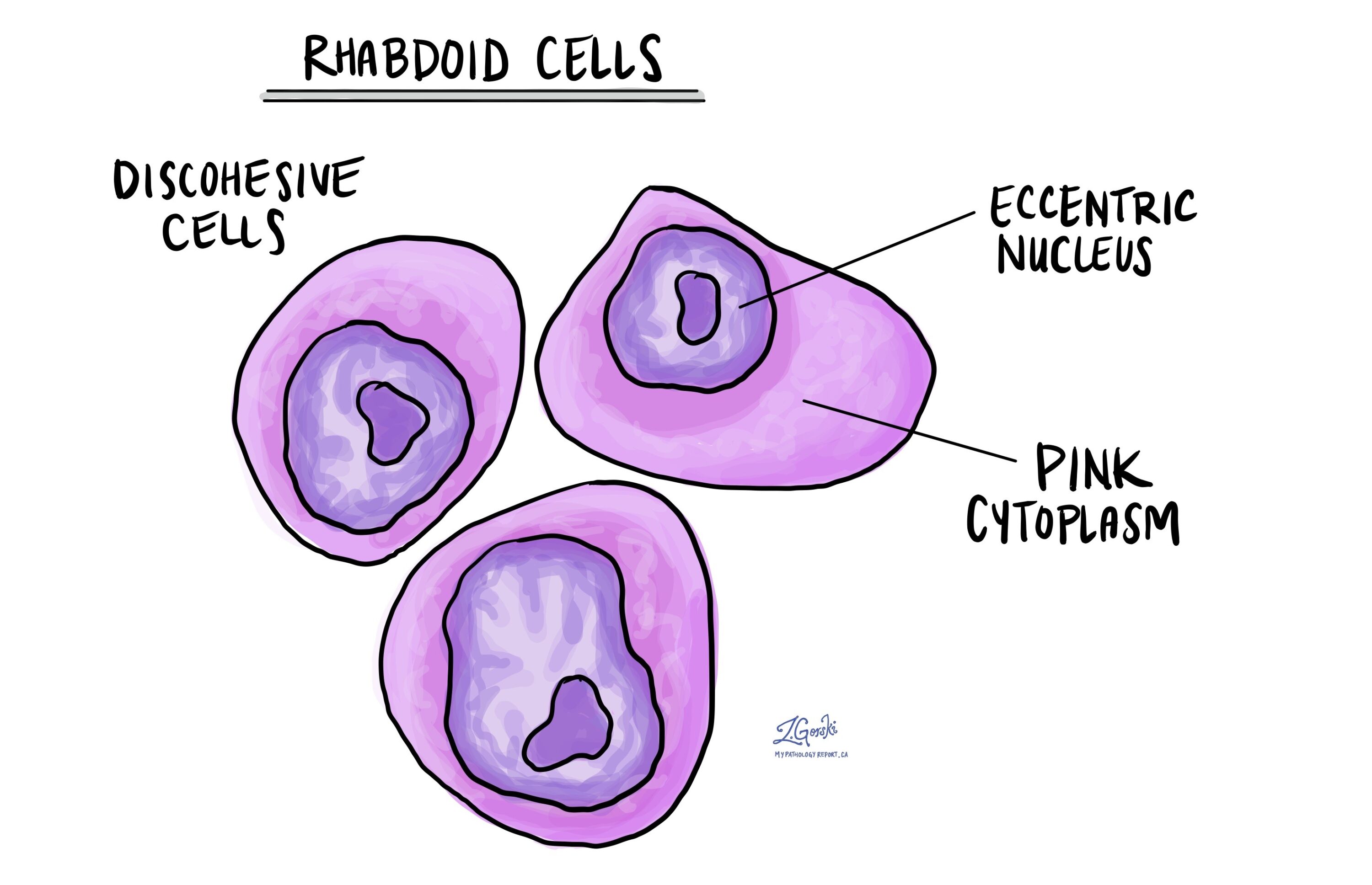

Under the microscope, rhabdoid cells have a very distinctive appearance. Pathologists recognize these cells by several unique features:

-

The cells are usually large, round, or oval, and often appear separated from each other (discohesive).

-

Each cell contains a large, irregularly placed (eccentric) nucleus—the part that contains DNA.

-

The nucleus often has one or more noticeable central structures called nucleoli.

-

These cells have abundant cytoplasm (the material surrounding the nucleus) that appears bright pink when stained with routine laboratory stains.

-

Often, rhabdoid cells contain dense, rounded structures in the cytoplasm, called inclusion-like bodies, made of protein filaments.

Identifying these features helps pathologists recognize rhabdoid tumours and understand their aggressive nature.

How do pathologists test for rhabdoid cells?

Pathologists use special laboratory tests called immunohistochemistry (IHC) to confirm the presence of rhabdoid cells in order to confirm the presence of rhabdoid cells. These tests involve applying specific antibodies to a tumour sample to see if certain proteins are present or absent. Typical findings include:

-

Loss of INI1 (SMARCB1): Most rhabdoid tumours lose expression of the INI1 protein, which is normally present in healthy cells. Loss of this protein is an important marker that strongly supports the diagnosis.

-

Vimentin: This protein is usually present in rhabdoid tumours, helping confirm their identity.

-

Cytokeratins and Epithelial Membrane Antigen (EMA): These markers can be positive in rhabdoid tumours, especially those involving epithelial or carcinoma-like features.

-

Muscle-specific markers (like desmin and MyoD1): These markers are tested to help distinguish true muscle-derived tumours (such as rhabdomyosarcoma) from rhabdoid tumours. Typically, true rhabdoid tumours are negative for these muscle-specific markers.

The combination of these tests helps pathologists make an accurate diagnosis, determine whether rhabdoid cells are present, and clarify the type of tumour.

Does the presence of rhabdoid cells affect treatment?

Yes, rhabdoid cells often indicate a tumour with more aggressive behaviour, and typically a worse prognosis compared to tumours without rhabdoid features. Because of this, tumours containing rhabdoid cells may require more intensive or aggressive treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy. Identifying rhabdoid cells helps your healthcare team develop an appropriate treatment plan tailored specifically to the type and aggressiveness of your tumour.