by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD

August 9, 2025

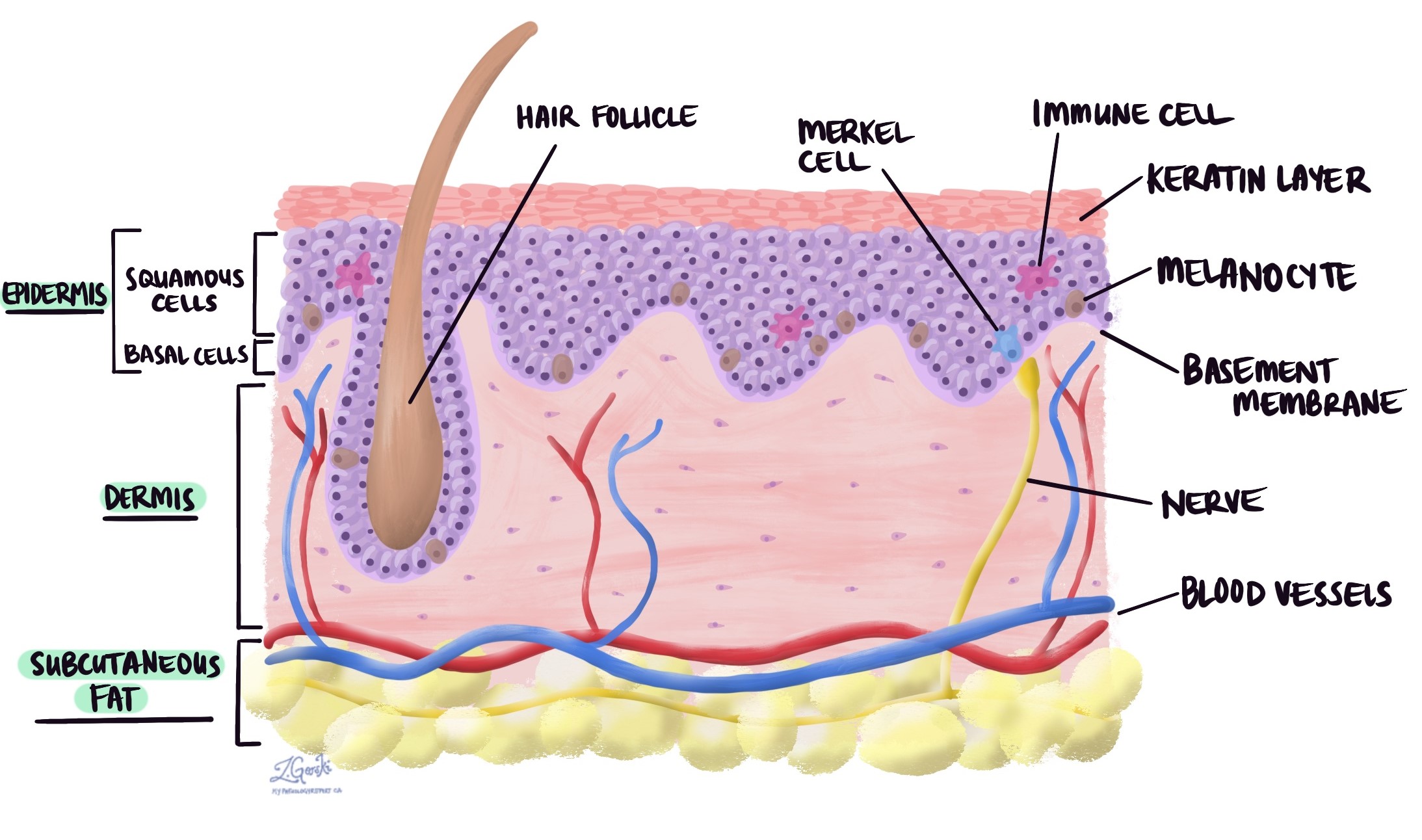

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is one of the most common types of skin cancer. It starts from squamous cells, which are the flat cells that normally form the outermost layer of the skin (the epidermis).

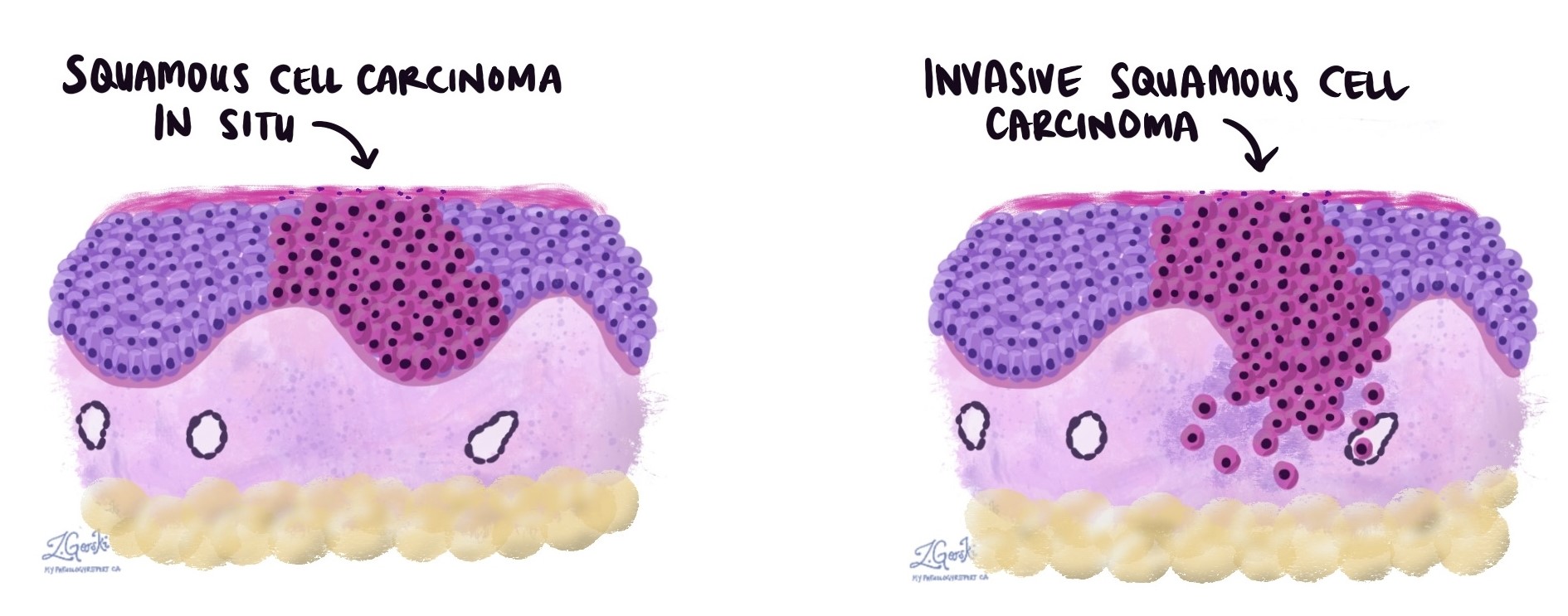

SCC occurs when cancerous squamous cells grow beyond the epidermis into the deeper layers of the skin. Pathologists describe this as invasion. This deeper growth increases the risk that the cancer can spread to other parts of the body, such as lymph nodes or distant organs.

In many cases, SCC develops from a precancerous condition like squamous cell carcinoma in situ or actinic keratosis which is confined to the surface layer and has not yet invaded deeper tissue.

What are the symptoms of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin?

The appearance and symptoms of SCC can vary depending on where it occurs, how deep it has grown, and whether it is near nerves or blood vessels.

Common signs and symptoms include:

-

A firm lump or nodule that may feel rough or scaly on the surface.

-

An open sore or ulcer that does not heal or that heals and returns.

-

A wart-like growth with a raised surface.

-

Crusting or bleeding, even after minor injury.

-

Pain, tenderness, or numbness, especially if the cancer is growing around a nerve.

Because SCC most often occurs on sun-exposed skin—such as the face, ears, neck, scalp, and hands—any new or changing lesion in these areas should be assessed promptly. However, it can also develop on skin that is not regularly exposed to the sun.

What causes squamous cell carcinoma of the skin?

The main cause is long-term damage to skin cells from ultraviolet (UV) radiation in sunlight. Similar damage can be caused by artificial UV sources such as tanning beds.

Other risk factors include:

-

Weakened immune system (for example, from anti-rejection medications after an organ transplant or from HIV infection).

-

Chronic inflammation or scarring in the skin.

-

Previous radiation therapy to the area.

Understanding the cause is important because it can influence follow-up care. For example, people with immune suppression are more likely to develop additional skin cancers and require more frequent skin checks.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis is made by removing a small sample of the tumour in a biopsy or the entire tumour and examining it under the microscope. The pathologist looks for abnormal squamous cells that have grown into the deeper layers of the skin. The report will include details such as tumour grade, thickness, depth, margin status, and whether perineural or lymphovascular invasion is present.

Tumour grade

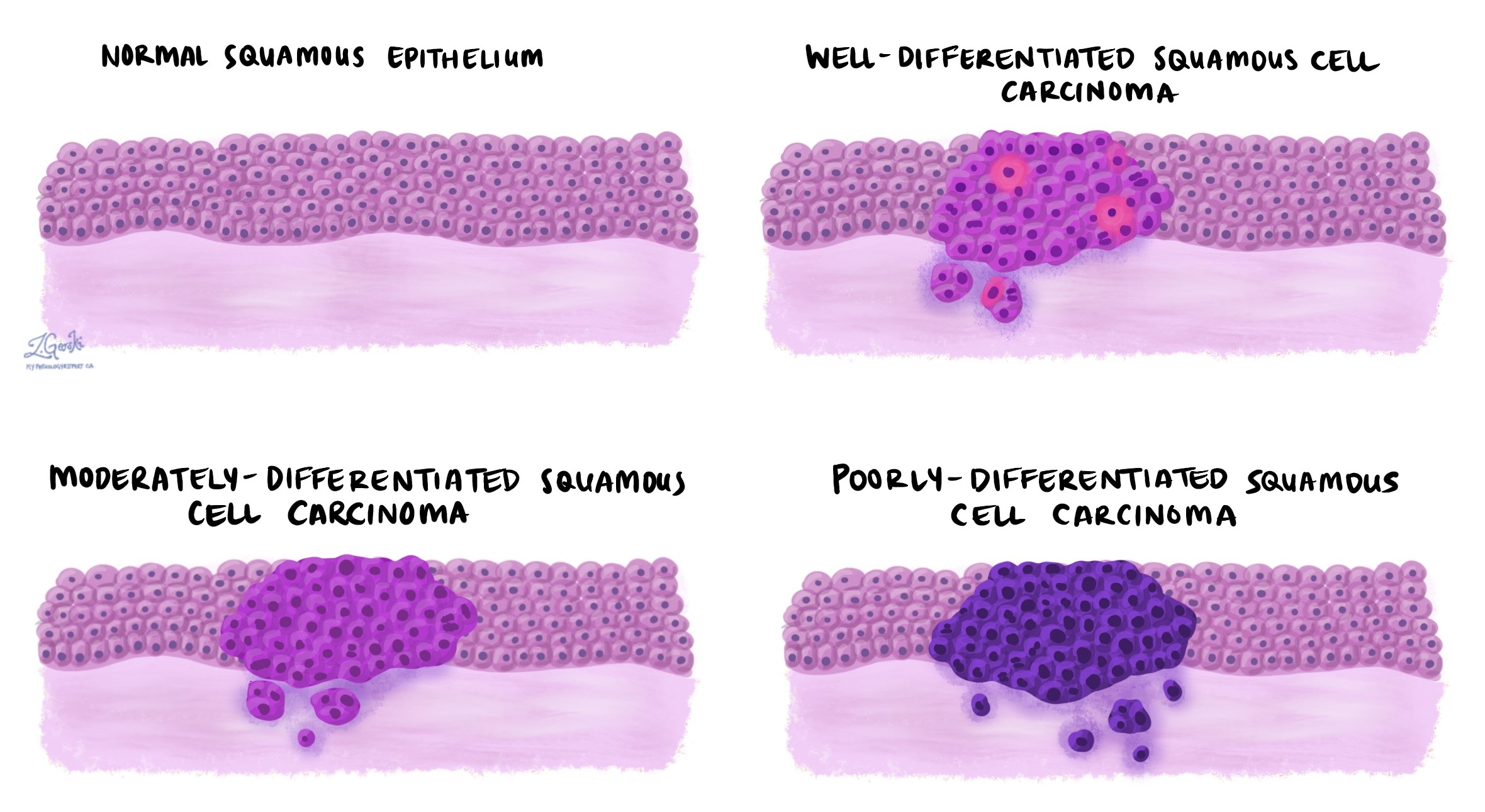

Tumour grade describes how abnormal the cancer cells look compared to normal squamous cells. It also reflects how quickly the cancer is likely to grow and spread.

-

Well differentiated (grade 1): Cells look very similar to normal squamous cells. These tumours tend to grow more slowly and have a lower risk of spreading.

-

Moderately differentiated (grade 2): Cells look different from normal but still show features of squamous cells. These have a moderate growth rate and a moderate risk of recurrence or spread.

-

Poorly differentiated (grade 3): Cells look very abnormal and may not resemble squamous cells at all. These tumours are more aggressive, more likely to spread, and often require closer follow-up and more aggressive treatment.

The grade is important for prognosis and helps guide treatment decisions. Higher-grade tumours are more likely to need additional therapy, such as radiation, after surgery.

Keratoacanthoma-like squamous cell carcinoma

Some invasive SCCs resemble keratoacanthomas, which are dome-shaped growths that can sometimes shrink without treatment. However, keratoacanthoma-like SCC behaves like cancer and can invade deeper tissue. Because there is no reliable way to predict behaviour, these tumours are treated as SCC and are usually removed surgically.

Tumour thickness and Clark’s level

Tumour thickness measures how far the cancer has grown from the surface of the skin into the deeper layers. A tumour thicker than 2 mm is more likely to spread to lymph nodes or return after treatment, so it is considered higher risk.

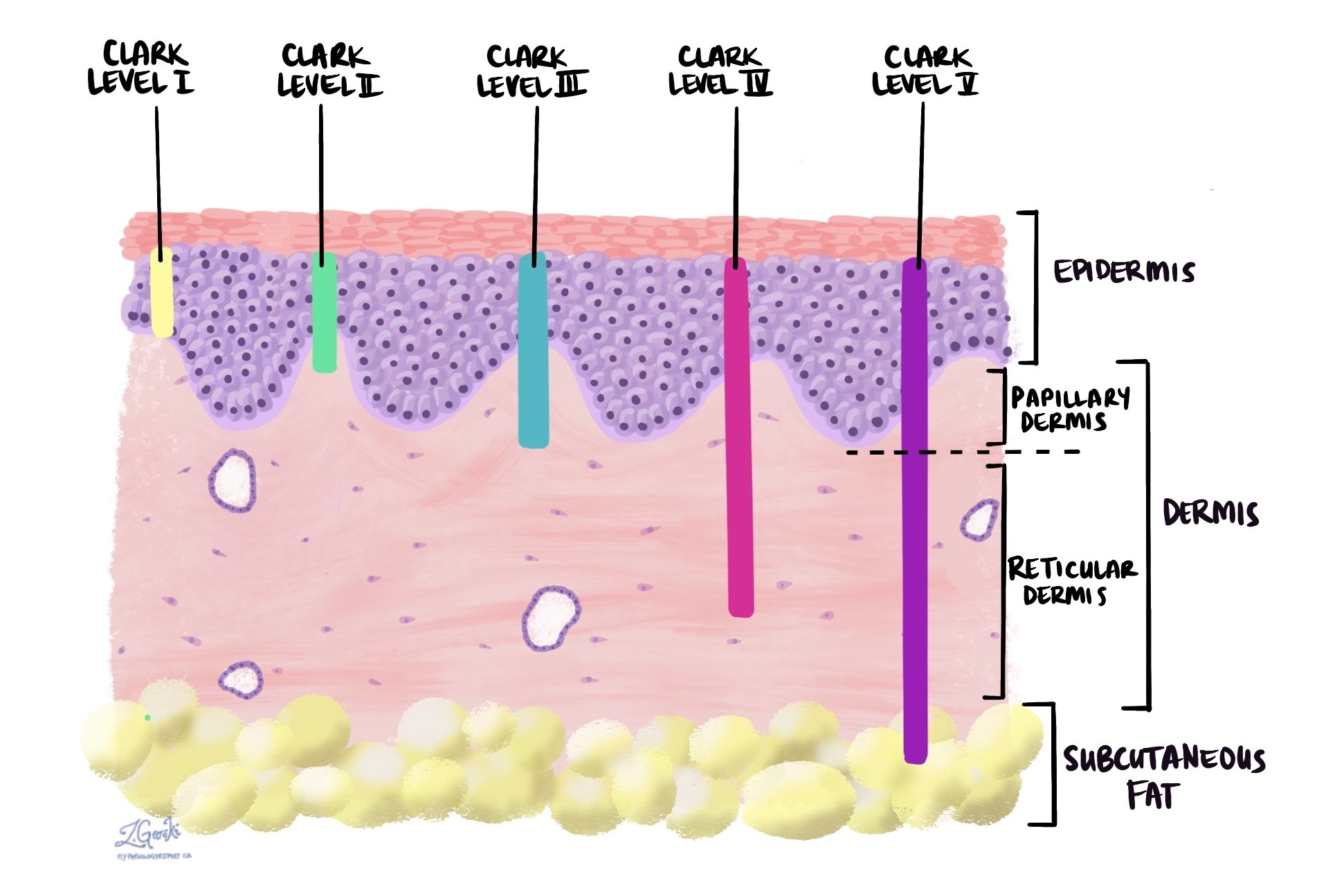

Clark’s level is another way to describe how deep the tumour has grown, using the skin’s layers as reference points:

-

Level I: Only in the epidermis (in situ).

-

Level II: Into the upper dermis (papillary dermis).

-

Level III: Through the papillary dermis.

-

Level IV: Into the lower dermis (reticular dermis).

-

Level V: Into the fat beneath the skin (subcutaneous tissue).

Both tumour thickness and Clark’s level are important because deeper tumours have a higher chance of spreading and may require more extensive surgery or additional treatments.

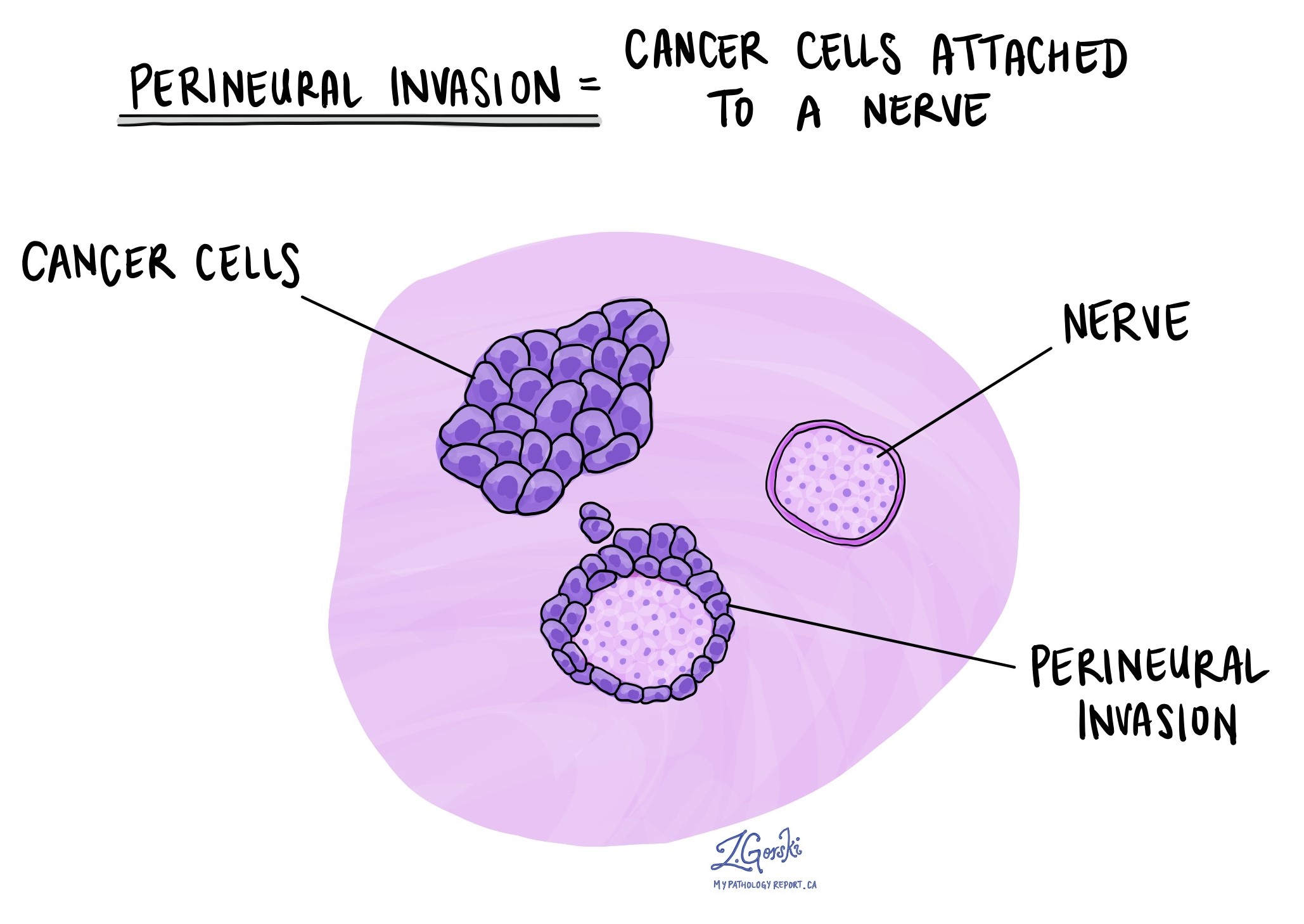

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion (PNI) means cancer cells are growing along or into a nerve. This can allow the cancer to travel further into the body and makes it harder to remove completely with surgery. It is associated with a higher risk of recurrence and spread, especially to nearby critical structures such as the brain or spinal cord when the cancer is on the head or neck.

When perineural invasion is found, your doctor may recommend additional surgery or radiation therapy.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means cancer cells have entered a blood vessel or lymphatic channel. This is significant because it gives the cancer a direct route to spread to lymph nodes or distant organs.

When lymphovascular invasion is present, there is a higher risk of metastasis, and closer monitoring or additional treatment may be recommended.

Margins

A margin is the edge of the tissue removed during surgery. Pathologists examine margins to see if any cancer cells are present at the cut edge.

-

Negative margin: No cancer cells are at the edge. The tumour was likely fully removed, lowering the risk of recurrence.

-

Positive margin: Cancer cells are at the edge. This means some tumour may remain and additional treatment—often more surgery—is usually needed.

Margin status is critical for determining if surgery was successful and whether more treatment is necessary.

Completely excised vs. incompletely excised

A tumour is completely excised when all visible cancer is removed and margins are negative.

A tumour is incompletely excised when cancer cells are still present at the edge of the removed tissue. This increases the risk of recurrence and usually requires more surgery or other treatments.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs that help filter harmful substances. Cancer cells can travel to lymph nodes through lymphatic channels.

If lymph nodes are removed, the pathology report will include:

-

The number of nodes examined.

-

The number that contained cancer cells.

-

The size of the largest group of cancer cells. These groups are often described as tumor deposits.

Finding cancer in a lymph node means the cancer has started to spread. This may change the stage of the cancer and affect treatment recommendations.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

Was my tumour completely removed?

-

What was the grade and thickness of my tumour, and how does that affect my risk?

-

Were there signs of perineural or lymphovascular invasion?

-

Did the margins contain cancer cells?

-

Do I need further surgery or additional treatment such as radiation therapy?

- How often should I return for skin checks?

-

What steps can I take to reduce my risk of future skin cancers?