by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

February 15, 2024

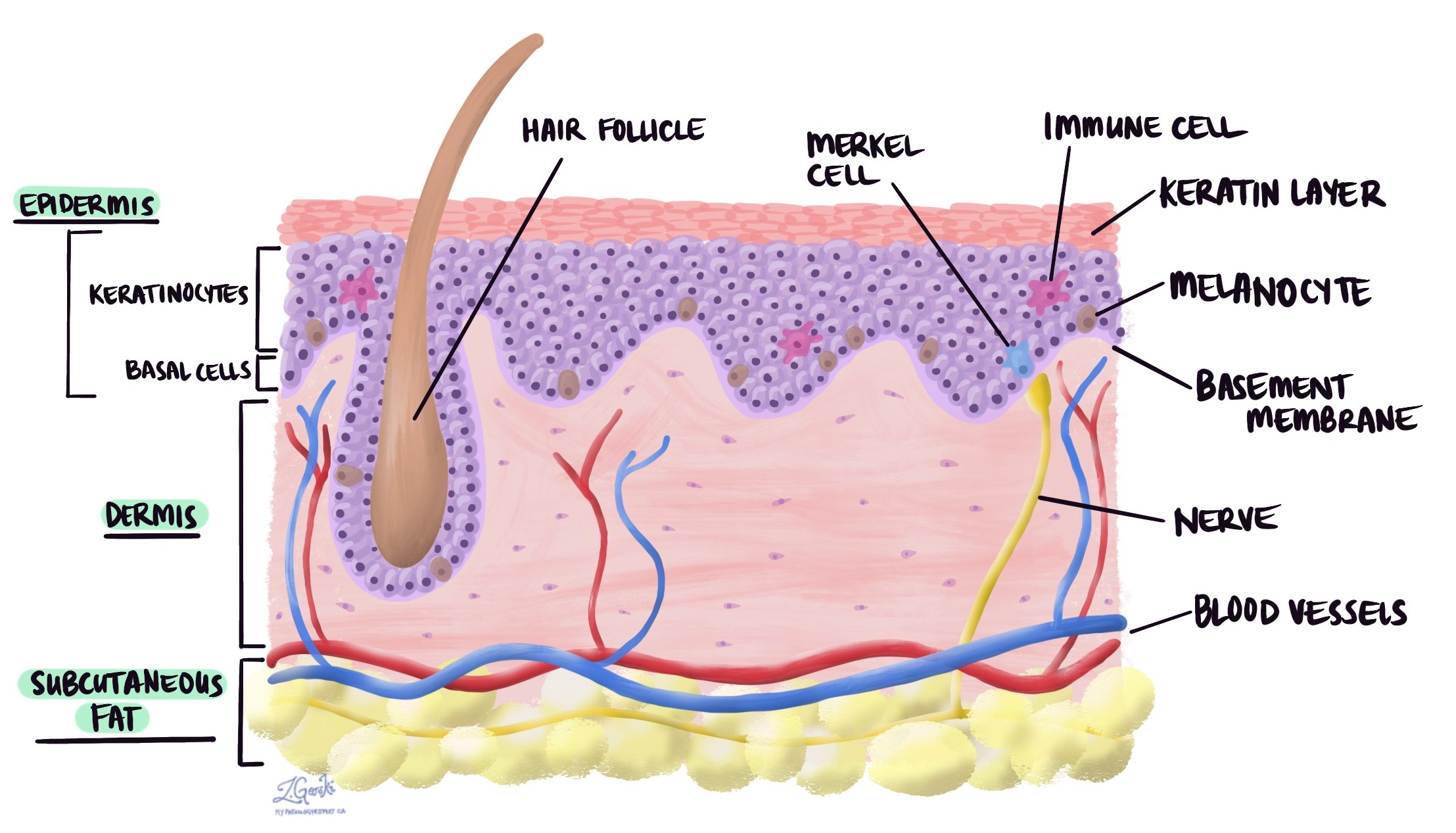

Actinic keratosis (AK) is a pre-cancerous skin disease. It is considered a pre-cancerous disease because, for some patients, the disease will change over time into a type of skin cancer called squamous cell carcinoma. It is made up of abnormal keratinocytes in a layer of the skin called the epidermis.

What causes actinic keratosis?

Actinic keratosis is a very common condition caused by long-term exposure to the sun. This condition commonly occurs on the face, lips, ear, back of the hands, arms, and scalp. However, this condition can develop anywhere on the body where the skin has been exposed to the sun for long periods. When similar changes affect the lips, it is called actinic cheilitis. It is not uncommon for people to have multiple areas of the skin with actinic keratoses. Older age, fair skin, and chronic sun exposure are risk factors for developing this condition.

What are the symptoms of actinic keratosis?

Actinic keratosis is a skin condition that shows up as rough, scaly patches on areas of the skin often exposed to the sun, like the face, hands, and arms. These patches can be small, sometimes less than an inch wide, and may feel like sandpaper. They can appear in various colors, including pink, red, or even the same color as your skin. The spots might itch or burn, making them uncomfortable.

What does actinic keratosis look like under the microscope?

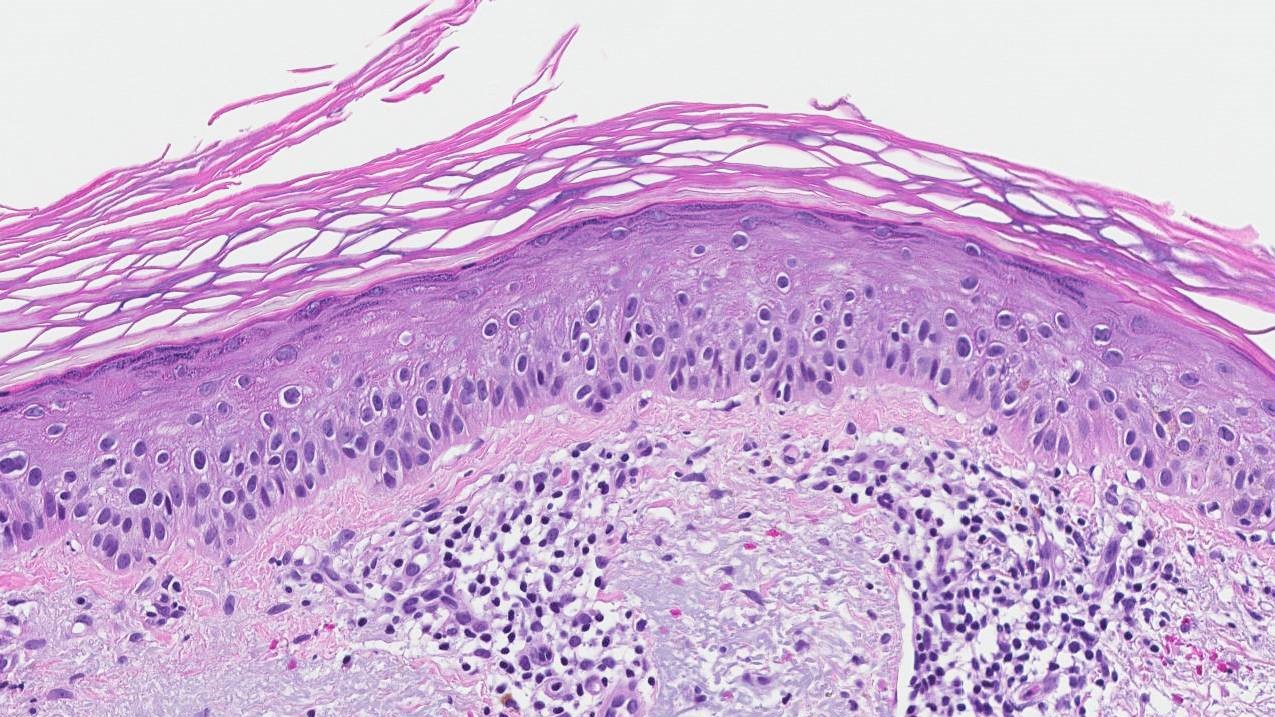

Actinic keratosis is characterized by the presence of abnormal skin cells called keratinocytes within the top layer of the skin, known as the epidermis. These cells appear irregular in shape and size, with nuclei that are darker and more prominent than normal, indicating they are not maturing as they should. The outermost layer of the skin, which usually sheds its dead cells, retains these nuclei in a condition called parakeratosis, signifying a disruption in the skin’s natural renewal process. Additionally, there is a noticeable thickening of the skin surface in some areas due to an accumulation of these abnormal cells.

Beneath these changes, the skin shows signs of damage from long-term sun exposure, including solar elastosis, where the elastic fibers in the deeper layer of the skin become thick and discolored. This is a clear indicator of the skin’s response to UV radiation. Accompanying these features, there may be an inflammatory response with immune cells and increased small blood vessels, reflecting the body’s reaction to the cellular damage. The overall picture is one of disorganized skin cell growth and sun-induced damage, highlighting the precancerous nature of actinic keratosis and the potential for progression to more serious skin conditions if left unchecked.

Variants of actinic keratosis

When pathologists say actinic keratosis has different “variants,” it means that this condition can appear in several different forms, each with its specific look and characteristics. Importantly, the risk of transformation to invasive squamous cell carcinoma varies among the different variants of actinic keratosis. Below are several recognized variants of actinic keratosis and the importance of each, including their potential risk of becoming invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Classic actinic keratosis

This is the most common variant, characterized by rough, scaly patches on sun-exposed skin. The risk of progression to squamous cell carcinoma is generally considered low but is significant over time, especially if the lesions are numerous or left untreated. The hyperkeratotic surface, which is thicker than other variants, can sometimes obscure the degree of underlying dysplasia (abnormal development), making it difficult to assess the risk accurately.

Atrophic actinic keratosis

Atrophic actinic keratosis appears as thin, flat, or slightly depressed lesions with a smooth surface. Despite their less threatening appearance, atrophic lesions can be deceptive, as the lack of a protective keratin layer may facilitate easier progression to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Their atrophic (thinned) nature does not necessarily imply a lower risk of malignancy.

Pigmented Actinic Keratosis

This variant can resemble two other skin conditions – lentigo maligna and seborrheic keratosis – due to its pigmented (colored) appearance. The presence of melanin (pigment) in addition to dysplastic keratinocytes adds a diagnostic challenge but does not inherently increase the risk of progression to squamous cell carcinoma. However, the pigmentation may mask the extent of dysplasia, potentially delaying diagnosis and treatment.

Lichenoid actinic keratosis

Lichenoid actinic keratosis is characterized by a dense, band-like inflammatory infiltrate, resembling lichen planus under the microscope. This variant may be more prone to inflammation and subsequent tissue damage, possibly increasing the risk of malignant transformation. The inflammatory environment might contribute to genetic mutations leading to squamous cell carcinoma

Bowenoid actinic keratosis

Bowenoid actinic keratosis closely resembles a non-invasive type of skin cancer called squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease) with full-thickness epidermal dysplasia. Given its histological similarity to squamous cell carcinoma in situ, the risk of progression to invasive cancer is considered high. Prompt treatment is crucial to prevent the advancement of invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Acantholytic actinic keratosis

This variant shows features of acantholysis (breakdown of cellular adhesion within the epidermis), leading to the formation of clefts or spaces between cells. Acantholytic actinic keratosis might indicate an aggressive local growth pattern, but the exact risk of progression to invasive squamous cell carcinoma is still not clearly understood. The presence of acantholysis may signal an increased likelihood of genetic mutations conducive to cancer development.

Hypertrophic actinic keratosis

Hypertrophic actinic keratosis is characterized by a pronounced thickening of the skin with significant hyperkeratosis. This variant is often more resistant to treatment and may have a higher risk of progression to squamous cell carcinoma, especially if lesions are persistent or recurrent. The thickened, hyperkeratotic nature can obscure the depth and severity of dysplasia.

About this article

Doctors wrote this article to help you read and understand your pathology report. Contact us if you have any questions about this article or your pathology report. Read this article for a more general introduction to the parts of a typical pathology report.