By Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

June 20, 2025

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) is an aggressive type of lung cancer made up of neuroendocrine cells. Neuroendocrine cells are specialized cells found throughout the body that produce chemicals called hormones. These hormones help regulate the activity of other cells and tissues. In the lungs, LCNEC typically begins in the walls of the airways, often in the central part of the lung.

LCNEC grows quickly and can spread rapidly to other parts of the body, making it a serious condition that usually requires immediate treatment.

Can large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung spread to other parts of the body?

Yes. LCNEC is an aggressive cancer and often spreads (metastasizes) to other areas, including the lymph nodes, liver, adrenal glands, bones, and brain. Early detection and treatment are very important to help reduce this risk.

What causes large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung?

The most common cause of LCNEC is cigarette smoking. People who have smoked or have been exposed to second-hand smoke for many years have a higher risk of developing LCNEC compared to non-smokers.

What are the symptoms of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung?

Symptoms of LCNEC vary depending on the size and location of the tumour. Common symptoms include:

-

Shortness of breath.

-

A persistent or worsening cough.

-

Coughing up blood.

-

Chest pain or pressure.

If the cancer has spread to other parts of the body (metastatic disease), additional symptoms may appear, such as:

-

Unexplained weight loss.

-

Bone pain.

-

Abdominal pain.

-

New or worsening headaches or neurological symptoms.

What is the difference between large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and large cell carcinoma of the lung?

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) and large cell carcinoma of the lung sound similar but are different types of lung cancer.

-

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is made up of specialized cells called neuroendocrine cells. These cells produce hormones and other chemical messengers. LCNEC tends to be aggressive and often spreads quickly to other parts of the body. Special tests called immunohistochemistry can identify the presence of neuroendocrine cells by detecting certain proteins, including chromogranin, synaptophysin, and CD56.

-

Large cell carcinoma (without neuroendocrine features) is also made up of large, abnormal-looking cells. However, these cells do not have the specialized neuroendocrine markers and features. Large cell carcinoma can be aggressive but typically does not behave in the same way as LCNEC and is managed differently.

Distinguishing these two cancers is important because treatment approaches and prognosis can differ significantly.

What is the difference between large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung?

Both large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) and small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (small cell carcinoma) of the lung arise from neuroendocrine cells, but they differ in their microscopic appearance, behaviour, and treatment.

-

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) has large tumour cells with more visible features under the microscope. The cells usually have abundant pink cytoplasm and clearly visible nucleoli, and they tend to form patterns such as groups or clusters. LCNEC grows rapidly and is aggressive but is treated slightly differently from small cell carcinoma.

-

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma consists of much smaller tumour cells that have less cytoplasm and dense, dark nuclei. These tumour cells often appear crowded together under the microscope. Small cell carcinoma is also very aggressive, usually spreads rapidly, and is strongly linked to cigarette smoking. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy, rather than surgery, are usually the primary treatments for small cell carcinoma.

Clearly distinguishing LCNEC from small cell carcinoma is important because each requires specific and different treatments to achieve the best possible outcome.

How is large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung diagnosed?

LCNEC is usually diagnosed when a small tissue sample (biopsy) is taken from the lung and examined under a microscope by a pathologist (a doctor who specializes in diagnosing diseases). The biopsy is often obtained by procedures such as fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) or core needle biopsy. Imaging studies like CT scans or chest X-rays often lead doctors to suspect LCNEC and request a biopsy.

What does large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, LCNEC consists of large, abnormal-looking cells grouped in various patterns. Pathologists use descriptive terms such as organoid, nested, trabecular, palisading, and rosettes to describe how the tumour cells are arranged.

These cells typically have moderate amounts of pink (eosinophilic) cytoplasm, which is the substance filling the cells. They also have large, irregular-looking nuclei that contain clumps of genetic material (chromatin). These clumps often look coarse or speckled. Additionally, cells usually have prominent spots called nucleoli, where the genetic material is concentrated.

To confirm the diagnosis of LCNEC, your pathologist will count the number of dividing tumour cells (mitotic figures) under the microscope. LCNEC typically shows a high number of mitotic figures (more than 10 in an area of 2 square millimeters). Tumour cell death, known as necrosis, is also common but not mandatory for diagnosis.

What additional tests are performed to confirm the diagnosis?

Your pathologist may order a special test called immunohistochemistry (IHC) to confirm the diagnosis. IHC allows pathologists to see which proteins the tumour cells produce. LCNEC typically produces proteins normally found in neuroendocrine cells. Tumour cells in LCNEC usually test positive for one or more neuroendocrine markers, including chromogranin, synaptophysin, and CD56.

LCNEC may also test positive for a marker called TTF-1, although this marker is found in other types of lung cancers too.

Spread through air spaces (STAS)

Spread through air spaces (STAS) describes a pattern of lung cancer growth where cancer cells spread into nearby air spaces within the lung. The presence of STAS often means a higher risk of the cancer returning (recurrence) and generally indicates a poorer prognosis, especially for early-stage tumours.

Pathologists look carefully at the lung tissue surrounding the tumour under a microscope to see if cancer cells are floating freely or attached separately to the alveolar walls, away from the main tumour mass.

Multiple tumours in the lung

It is possible to have more than one tumour in the lung. When multiple tumours are found, your pathology report will describe each tumour separately.

There are two reasons why multiple tumours might occur:

-

Spread from one tumour: Likely if all tumours are the same type (such as all being adenosquamous carcinomas). Smaller tumours are called nodules if found on the same side of the lung, and metastases if found on the opposite lung.

-

Separate tumours: If tumours are of different types (for example, one adenosquamous carcinoma and one squamous cell carcinoma), they are likely to have developed separately. These tumours are considered separate primary cancers.

Pleural invasion

The pleura is a thin lining surrounding the lungs and the inside of the chest wall. When cancer cells spread to the pleura, it is referred to as pleural invasion. Pleural invasion is important because it typically means:

-

Higher tumour stage: Cancer that invades the pleura is considered more advanced.

-

Poorer prognosis: Pleural invasion often leads to complications, such as fluid buildup (pleural effusion), which can cause shortness of breath, chest pain, and cough.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means cancer cells have entered small vessels (blood vessels or lymphatic channels) within the lung tissue. This is important because cancer cells in these vessels can travel to lymph nodes or distant parts of the body, leading to further metastasis (spread).

Margins

A margin is the edge of the tissue removed during surgery. Pathologists carefully check margins under the microscope to ensure the entire tumour has been removed.

-

Negative margin: No cancer cells at the cut edge (the goal of surgery).

-

Positive margin: Cancer cells present at the cut edge, meaning some cancer may still be in your body. Positive margins may require additional surgery or radiation therapy.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped organs that play an essential role in the immune system. They are connected throughout the body by small channels called lymphatic vessels. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour through these lymphatic vessels and into nearby lymph nodes—a process called lymph node metastasis.

Lymph nodes in the lungs and chest are grouped into specific areas called lymph node stations. There are 14 different lymph node stations, each with a specific location:

-

Station 1: Lower cervical, supraclavicular, and sternal notch lymph nodes.

-

Station 2: Upper paratracheal lymph nodes.

-

Station 3: Prevascular and retrotracheal lymph nodes.

-

Station 4: Lower paratracheal lymph nodes.

-

Station 5: Subaortic (aortopulmonary window) lymph nodes.

-

Station 6: Para-aortic lymph nodes (near the ascending aorta or phrenic nerve).

-

Station 7: Subcarinal lymph nodes (below the carina, where the trachea splits into bronchi).

-

Station 8: Paraesophageal lymph nodes (alongside the esophagus below the carina).

-

Station 9: Pulmonary ligament lymph nodes.

-

Station 10: Hilar lymph nodes (at the lung hilum, where airways enter the lung).

-

Station 11: Interlobar lymph nodes (between lung lobes).

-

Station 12: Lobar lymph nodes (within lung lobes).

-

Station 13: Segmental lymph nodes (within lung segments).

-

Station 14: Subsegmental lymph nodes (within smaller lung subsegments).

If lymph nodes are removed during surgery, a pathologist carefully examines them under a microscope to see if they contain cancer cells. The pathology report typically includes:

-

The total number of lymph nodes examined.

-

The locations (stations) of the lymph nodes examined.

-

The number of lymph nodes containing cancer cells.

-

The size of the largest group of cancer cells (often called a “focus” or “deposit”).

Lymph node examination provides important information that helps your doctor determine the cancer’s pathologic nodal stage (pN). It also helps predict the likelihood that cancer cells may have spread to other parts of the body, guiding decisions about additional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy.

Pathologic stage (pTNM) for large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung

LCNEC is staged using the TNM staging system, which provides important information about prognosis and treatment options.

Tumour stage (pT)

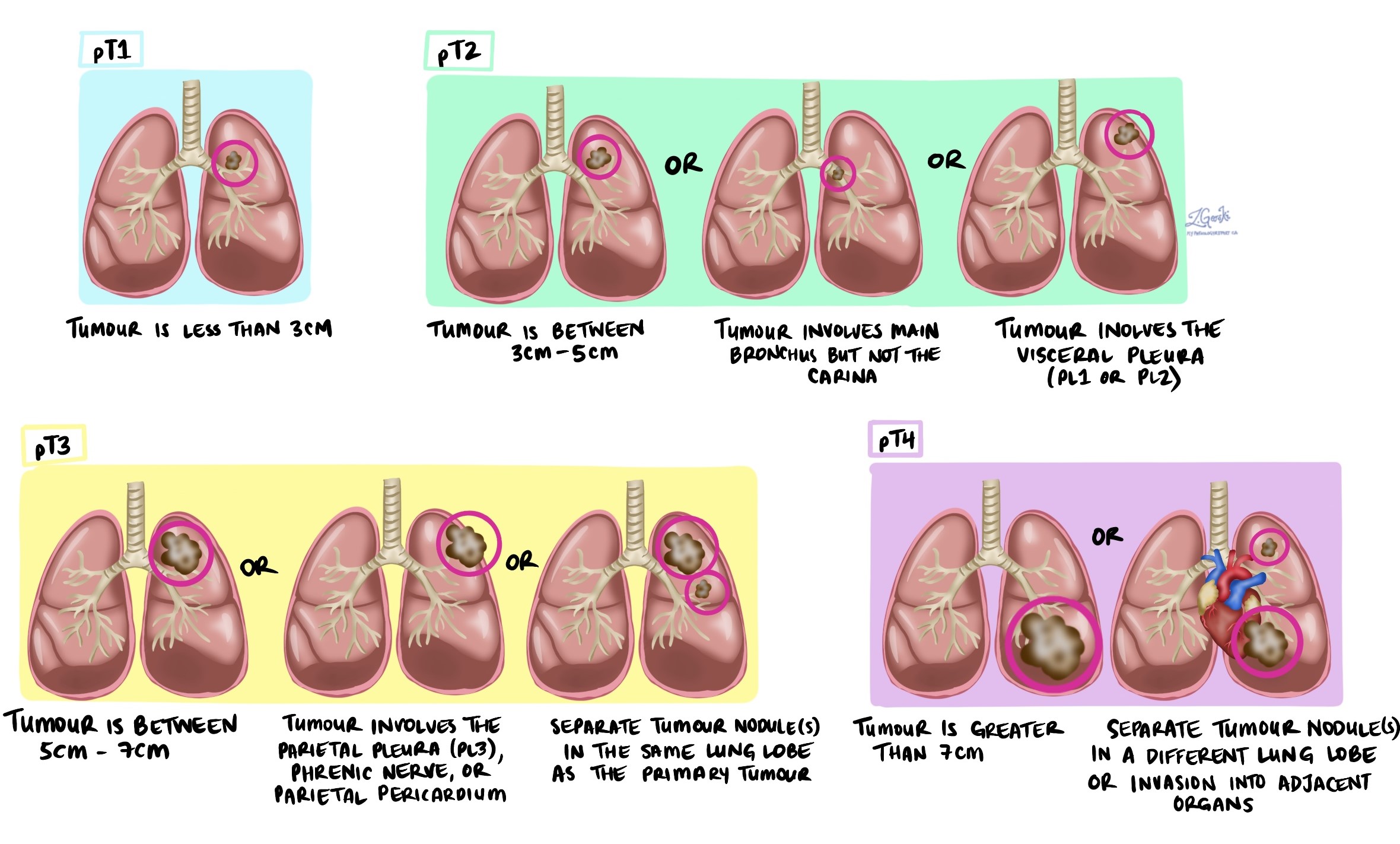

The tumour (T) stage is based on tumour size and spread:

-

T1: Tumour is 3 cm or smaller and contained within the lung.

-

T2: Tumour is larger than 3 cm but not more than 5 cm, or it invades the visceral pleura or partially blocks a major airway.

-

T3: Tumour is larger than 5 cm but not more than 7 cm or invades nearby chest wall, diaphragm, or other nearby tissues.

-

T4: Tumour is larger than 7 cm or invades the heart, major blood vessels, trachea, esophagus, or bones.

Nodal stage (pN)

The nodal (N) stage is based on tumour spread to lymph nodes:

-

NX: No lymph nodes were examined.

-

N0: No tumour cells in lymph nodes.

-

N1: Tumour cells found in lymph nodes within the lung or near the lung (stations 10-14).

-

N2: Tumour cells found in lymph nodes located around large airways and the middle of the chest (stations 7-9).

-

N3: Tumour cells found in lymph nodes on the opposite side of the chest or in the neck (stations 1-6).

Questions to ask your doctor:

-

What treatments are recommended for my LCNEC?

-

Has the tumour spread to my lymph nodes or other parts of my body?

-

What is my tumour stage, and what does it mean for my treatment?

-

Will I need additional tests or scans?

-

Should I see other specialists, such as an oncologist?

-

Are there clinical trials or new therapies available?

-

What is my prognosis, and what can I expect during treatment and recovery?