by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD FRCPC

August 8, 2025

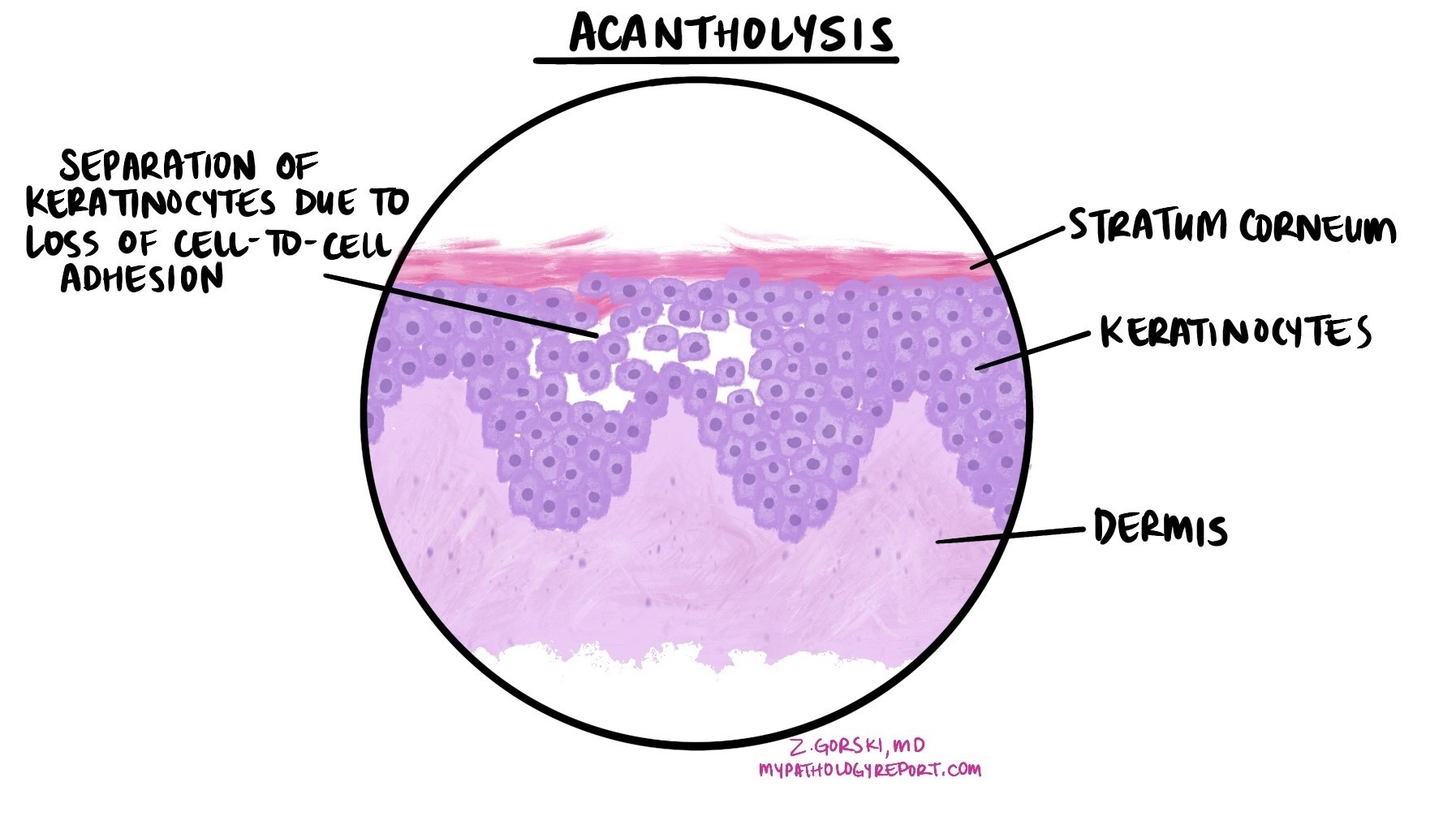

Pemphigus is a group of rare autoimmune diseases that affect the skin and mucous membranes (the moist surfaces inside your mouth, nose, throat, and genitals). The outer layer of these tissues is made of keratinocytes, which are flat cells arranged like tiles on a roof. In pemphigus, the immune system produces antibodies that target specific proteins responsible for holding keratinocytes together. When these proteins are damaged, the keratinocytes separate, making the skin and mucous membranes fragile and prone to blistering. Pathologists use the term acantholysis to describe this change.

These blisters are often soft (flaccid) and break easily, leaving raw, painful areas that may crust over or erode. Pemphigus is not contagious and cannot be spread from one person to another.

Types of pemphigus

There are four main types of pemphigus:

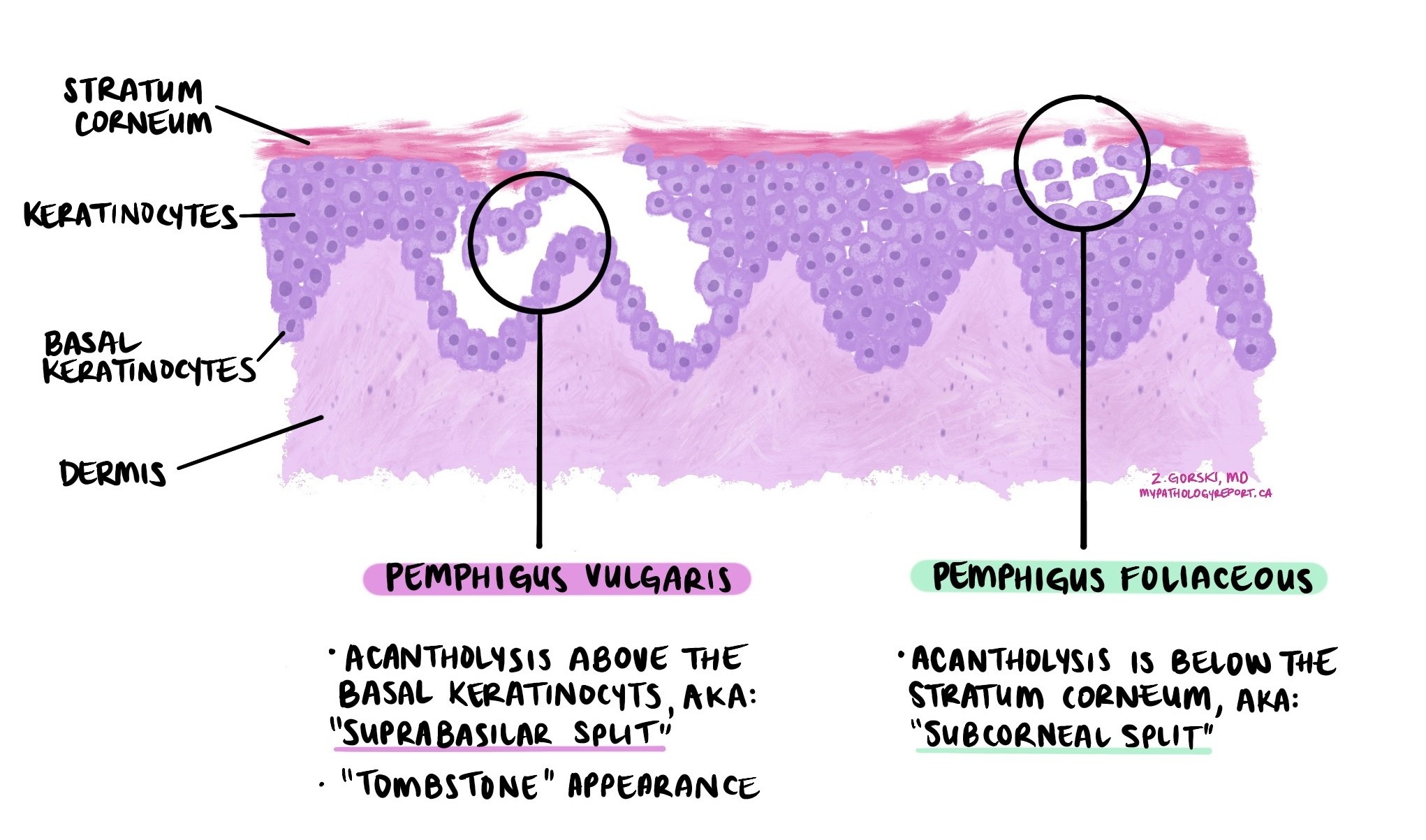

- Pemphigus vulgaris – The most common type, often starting in the mouth or other mucous membranes and sometimes spreading to the skin.

- Pemphigus foliaceus – Affects only the skin, causing more superficial crusts and erosions.

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus – A rare form linked to certain cancers, such as lymphoma or Castleman disease.

- IgA pemphigus – The rarest type, caused by a different antibody (IgA instead of IgG), usually affecting the skin without mucous membrane involvement.

What causes pemphigus?

Pemphigus happens when the immune system mistakenly attacks proteins that connect keratinocytes together. These proteins act like “molecular glue” between cells.

In most types, the immune system produces IgG antibodies against proteins called desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3. In IgA pemphigus, IgA antibodies target proteins such as desmocollin 1.

The reason this happens isn’t always clear, but several factors may increase risk:

-

Inherited immune system genes (for example, certain HLA types).

-

Other medical conditions, particularly in paraneoplastic pemphigus.

-

Certain medications (such as penicillamine, captopril, or some antibiotics).

-

Environmental factors in specific regions for endemic pemphigus foliaceus.

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of pemphigus vary by type.

- Pemphigus vulgaris – Painful blisters or open sores in the mouth or other mucous membranes. Skin blisters may appear later. Hoarseness can occur if the throat is involved.

- Pemphigus foliaceus – Superficial crusted areas on the face, scalp, or upper body; mucous membranes usually not affected.

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus – Severe mouth sores, eye irritation, skin rashes, and sometimes lung problems.

- IgA pemphigus – Small blisters or pustules forming ring-shaped patches with crust in the center. Mucous membranes are usually spared.

Doctors sometimes check for Nikolsky sign (skin peels when rubbed) or Asboe-Hansen sign (a blister spreads sideways when pressed).

How is this diagnosis made?

Diagnosis usually begins with a physical exam and review of symptoms. If pemphigus is suspected, your doctor may take a skin or mucous membrane biopsy—a small piece of tissue is removed and sent to a pathologist for examination under a microscope. Blood tests may also be ordered to look for specific antibodies.

What does pemphigus look like under the microscope?

When examined under a microscope, tissue from affected skin or mucous membranes shows acantholysis—a separation of keratinocytes—within the upper layers. In pemphigus vulgaris, this separation occurs just above the bottom layer of cells, which stay attached to the underlying tissue (a feature called the “tombstone sign”). In pemphigus foliaceus, the split is more superficial, just beneath the outermost skin layer (a feature called a “subcorneal split”). Inflammatory cells such as eosinophils may also be present.

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF)

DIF is a special test performed on a fresh tissue sample. It uses fluorescent dyes to detect antibodies or complement proteins that are stuck to the surface of keratinocytes. This test is important because it confirms the diagnosis and helps distinguish pemphigus from other blistering diseases.

- In pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus, DIF usually shows a “chicken-wire” pattern of IgG and C3 (a complement protein) between the keratinocytes.

- In IgA pemphigus, the test shows IgA between the keratinocytes.

- In paraneoplastic pemphigus, DIF may show antibodies not only between the keratinocytes but also along the junction between the top skin layer and the tissue underneath.

How is pemphigus treated?

Treatment focuses on calming the immune system and protecting the skin and mucous membranes:

-

Rituximab – A medication that targets the immune cells making the harmful antibodies; often the first choice in moderate to severe cases.

-

Corticosteroids – Such as prednisone, to quickly reduce inflammation.

-

Other immune-suppressing medicines – Such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, or dapsone (especially for IgA pemphigus).

-

Special treatments – For severe or resistant cases, intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), plasmapheresis, or immunoadsorption may be used.

-

Supportive care – Gentle skin cleansing, wound protection, and prevention of infection.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

Which type of pemphigus do I have?

-

What tests confirmed the diagnosis?

-

What treatments do you recommend, and why?

-

How will we monitor my response?

-

What side effects should I watch for?

-

Is my pemphigus likely to come back?