by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

August 30, 2025

HPV associated endocervical adenocarcinoma is a type of cervical cancer. It begins in the glandular cells that line the endocervical canal, which is the passage connecting the uterus to the vagina. These glandular cells normally produce mucus. When they become cancerous, they grow in an uncontrolled way and can spread into nearby tissues.

This cancer is called HPV associated because it is caused by infection with high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV). Over time, HPV changes the genetic material inside cervical glandular cells, which allows cancer to develop.

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of HPV associated endocervical adenocarcinoma depend on the size of the tumor and how far it has spread. Early-stage disease may not cause any symptoms and is sometimes discovered through a Pap test or HPV test.

When symptoms occur, they may include:

-

Unusual vaginal bleeding, especially after sex, between periods, or after menopause.

-

Watery or bloody vaginal discharge that may have a strong odor.

-

Pelvic pain or discomfort, including pain during or after sexual intercourse.

Why is this type of cancer called HPV associated?

HPV, or human papillomavirus, is a very common virus that infects the skin and mucous membranes. Some types are considered high risk because they can cause cervical cancer.

The types most often linked to endocervical adenocarcinoma are HPV 16 and HPV 18. These types are responsible for the majority of HPV-related cervical cancers worldwide. In most people, HPV infections clear on their own. In some, the virus remains in the cervix and causes abnormal cell growth over many years. If these changes are not detected and treated, they can progress to cancer.

How common is HPV associated endocervical adenocarcinoma?

This type of cancer is less common than HPV associated squamous cell carcinoma, which is another form of cervical cancer. However, the number of cases of endocervical adenocarcinoma has been increasing. One reason is that Pap tests are more effective at detecting squamous cancers than glandular cancers.

HPV associated endocervical adenocarcinoma is most often diagnosed between the ages of 30 and 50, but it can occur at any age.

How is the diagnosis made?

The diagnosis is made when tissue from the cervix is removed and examined under the microscope by a pathologist. Testing may begin when abnormal glandular cells are seen on a Pap test or when high-risk HPV is detected.

Procedures used to confirm the diagnosis include:

-

Pap test to look for abnormal glandular cells.

-

HPV test to identify infection with high-risk virus types.

-

Cervical biopsy to remove a small piece of suspicious tissue.

-

Endocervical curettage to scrape cells from the endocervical canal.

-

Cone biopsy or LEEP to remove a larger, cone-shaped portion of the cervix, which allows the pathologist to see how deep the cancer has grown and whether it extends to the surgical edges.

What does HPV associated endocervical adenocarcinoma look like under the microscope?

Under the microscope, the tumor shows features that help distinguish it from non-HPV related cancers.

Pathologists often see:

-

Many dividing cells, called mitoses, especially at the top of the glands.

-

Dying cells, called karyorrhexis.

-

Glands lined by columnar cells with enlarged, elongated, dark nuclei.

-

Pseudostratification, meaning the nuclei appear stacked in layers.

-

In moderately to well differentiated tumors, the glandular structures have smooth inner borders.

What other tests are used to confirm the diagnosis?

Pathologists may use additional tests to prove that HPV is causing the cancer and to distinguish it from other tumors.

-

Immunohistochemistry for p16: This protein is strongly increased in HPV-driven cancers. A block-like pattern of p16 staining supports the diagnosis.

-

In situ hybridization for HPV: This test detects HPV DNA or RNA inside the tumor cells and confirms that high-risk HPV is present.

-

Other immunohistochemical markers: Depending on the case, additional stains may be used to rule out cancers that started outside the cervix.

What is the Silva classification?

HPV associated endocervical adenocarcinoma can invade tissue in different ways. The Silva pattern-based classification helps pathologists describe these growth patterns and predict behavior.

-

Pattern A: The glands remain well formed and packed together without destructive invasion. No cancer is seen in blood vessels or lymphatic vessels. These tumors have a very low risk of spread.

-

Pattern B: Small groups of cancer cells break away from the glands and begin to invade destructively in limited areas. Lymphovascular invasion may or may not be present.

-

Pattern C: The cancer invades diffusely and irregularly with distorted glands and a fibrous reaction in the surrounding tissue. These tumors are most likely to show lymphovascular invasion and to spread to lymph nodes.

Patterns A tumors usually behave indolently and have a very low risk of recurrence. Patterns B and C carry a higher risk of spread and require more aggressive treatment.

How is the tumor measured and why is depth of invasion important?

The tumor is measured in three dimensions: length, width, and depth. These measurements help determine the pathologic stage.

-

Length is the distance the tumor extends from top to bottom on the surface.

-

Width is the distance across the cervix from side to side.

-

Depth of invasion is the distance from the surface layer down to the deepest cancer cells in the supporting tissue of the cervix.

Depth of invasion is especially important. A tumor that remains on the surface is called adenocarcinoma in situ and cannot spread until it invades deeper tissue. Once the cancer breaks through the basement membrane into the stroma, it is considered invasive.

Tumors less than 3 millimeters deep (stage IA1) carry a very low risk of spread. Tumors between 3 and 5 millimeters deep (stage IA2) carry a slightly higher risk. Tumors deeper than 5 millimeters (stage IB or higher) are more likely to spread and usually require more aggressive treatment.

Has the tumor spread outside of the cervix?

Large tumors may extend into nearby tissues and organs. Cancer can spread into the endometrium, the vagina, the parametrium, the bladder, or the rectum. This is called tumor extension. The presence of extension raises the stage and is associated with a higher chance of recurrence.

What does lymphovascular invasion mean?

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means that cancer cells have entered small lymphatic channels or blood vessels in the cervix. This increases the chance of spread to lymph nodes or distant organs.

Tumors with Silva Pattern B or C are more likely to show lymphovascular invasion. If it is present, doctors often recommend more aggressive treatment, including removal of lymph nodes and sometimes radiation or chemotherapy.

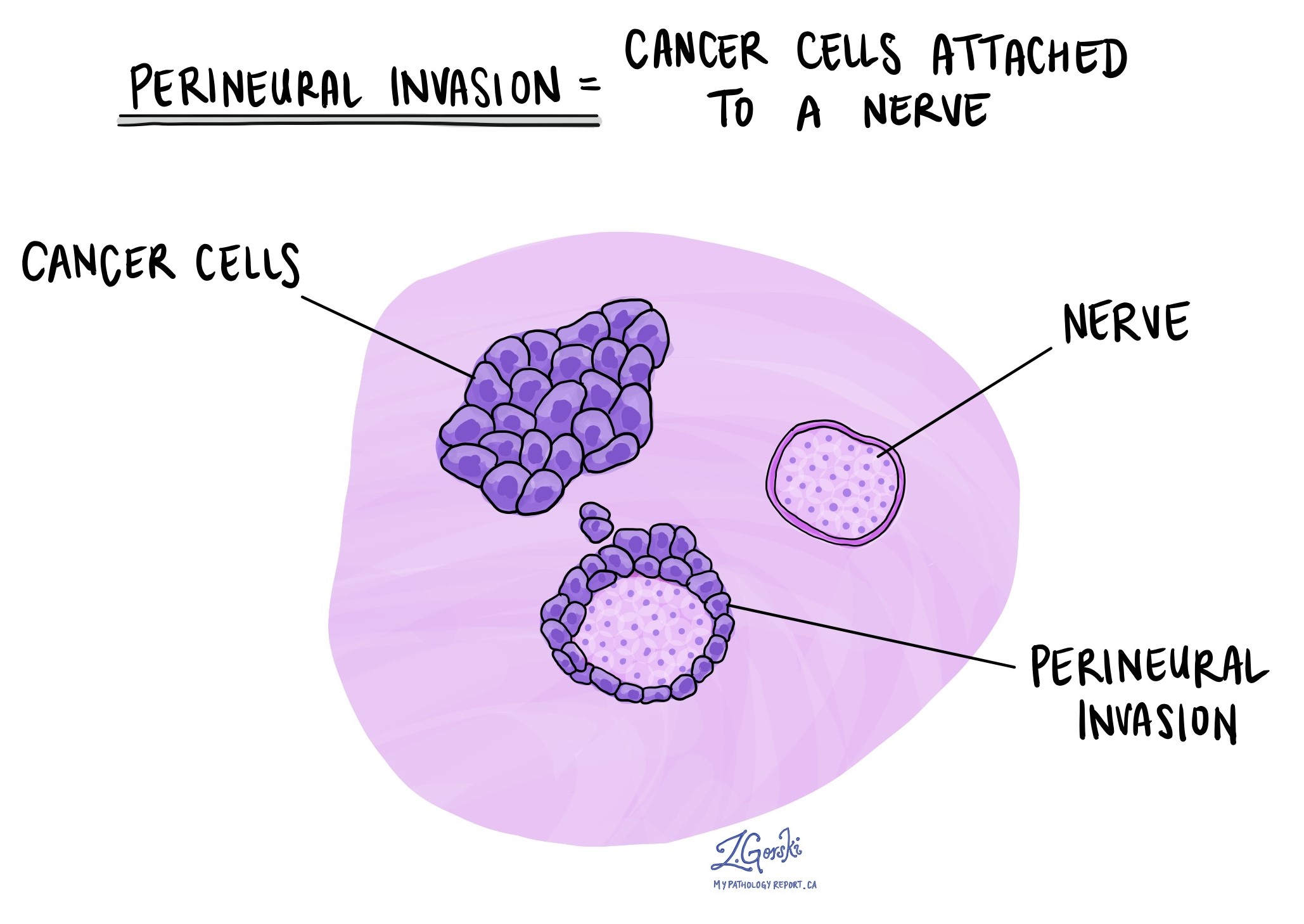

What does perineural invasion mean?

Perineural invasion (PNI) means that cancer cells are growing around or into small nerves in the cervix. Although less common than lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion is associated with more aggressive behavior and a higher chance of recurrence. It is seen most often in Silva Pattern C tumors.

What are margins and why are they important?

Margins are the edges of tissue removed during surgery. Pathologists examine the margins under the microscope.

-

A negative margin means no cancer is present at the edge, suggesting that the tumor was completely removed.

-

A positive margin means cancer reaches the edge, raising concern that cancer remains in the body.

Clear margins are especially important in cone biopsies and hysterectomies. When margins are positive, further treatment such as repeat surgery or radiation may be recommended.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune system organs that filter harmful substances and help fight infection. They are also a common first site of spread for cervical cancer.

During surgery, pelvic and sometimes para-aortic lymph nodes are removed and examined. The pathology report will describe how many nodes were removed, where they were located, and whether any contained cancer.

If cancer is present, the size of the deposit is measured:

-

Isolated tumor cells: Smaller than 0.2 millimeters.

-

Micrometastasis: Between 0.2 and 2 millimeters.

-

Macrometastasis: Larger than 2 millimeters.

A lymph node that contains cancer is described as positive. A node without cancer is described as negative. The number and size of positive nodes are important for staging and treatment planning.

How is HPV associated cervical cancer staged?

Staging describes how far the cancer has spread within the cervix and beyond. It is the most important factor for predicting outcome and deciding on treatment. Two systems are commonly used for cervical cancer: TNM and FIGO.

-

The TNM system records tumor size and spread in the cervix (T), whether lymph nodes contain cancer (N), and whether the cancer has spread to distant organs (M).

-

The FIGO system focuses on how far the cancer has spread beyond the cervix into surrounding tissues, lymph nodes, or distant sites. It is widely used by gynecologic oncologists to guide treatment planning.

TNM pathologic stage

-

The letter T describes how far the tumor has grown in and around the cervix.

-

T1a means that the tumor is only visible under the microscope and measures no more than five millimeters in depth and no more than seven millimeters in width.

-

T1b means that the tumor is visible or measures deeper than five millimeters or wider than seven millimeters.

-

T2a means that the tumor has spread beyond the cervix and uterus but has not entered the parametrium.

-

T2b means that the tumor has grown into the parametrium.

-

T3a means that the tumor involves the lower part of the vagina.

-

T3b means that the tumor reaches the pelvic wall or blocks a ureter, which can harm the kidneys.

-

T4 means that the tumor has grown into the bladder or rectum or has extended beyond the pelvis.

-

-

The letter N describes lymph nodes.

-

NX means that no nodes were removed.

-

N0 means that no cancer was found in the nodes.

-

N0 with isolated tumor cells means that only tiny clusters smaller than zero point two millimeters were present.

-

N1 means that a larger deposit of cancer was found in at least one node.

-

-

The letter M describes distant spread to organs such as the lungs or liver.

FIGO stage

-

Stage I means that the cancer is confined to the cervix.

-

Stage IA1 means that the depth of invasion is three millimeters or less.

-

Stage IA2 means that the depth of invasion is between three and five millimeters.

-

Stage IB1 means that the tumor is two centimetres or smaller.

-

Stage IB2 means that the tumor is more than two centimetres and up to four centimetres.

-

Stage IB3 means that the tumor is larger than four centimetres.

-

-

Stage II means that the cancer has spread beyond the cervix but not to the pelvic wall or the lower third of the vagina.

-

Stage IIA1 means that the tumor involves the upper vagina and measures four centimetres or less.

-

Stage IIA2 means that the tumor in the upper vagina is larger than four centimetres.

-

Stage IIB means that the tumor extends into the parametrium.

-

-

Stage III means more extensive local spread.

-

Stage IIIA means that the cancer involves the lower third of the vagina.

-

Stage IIIB means that the cancer reaches the pelvic wall or blocks a ureter.

-

Stage IIIC1 means that cancer is present in pelvic lymph nodes.

-

Stage IIIC2 means that cancer is present in para-aortic lymph nodes.

-

-

Stage IV means spread to nearby organs or to distant sites.

-

Stage IVA means invasion of the bladder or rectum.

-

Stage IVB means distant metastasis to organs such as the lungs, liver, or bones.

-

Staging guides treatment and helps predict outcome.

What is the prognosis?

The outlook depends on several factors, including stage, Silva pattern, lymphovascular invasion, and lymph node status.

-

Stage: Early-stage cancers have excellent survival rates, while advanced stages carry a lower chance of cure. Stage IA1 has nearly 100 percent survival. Stage III has about 34 percent survival, and stage IV has about 3 percent survival.

-

Silva pattern: Pattern A tumors have a very low risk of spread and rarely recur. Pattern B tumors have about a 4 percent risk of lymph node spread. Pattern C tumors have a much higher risk of lymph node spread, around 25 percent, and a higher risk of recurrence.

-

Other features: Lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, positive margins, and positive lymph nodes all increase the risk of recurrence.

-

Subtype and genetics: Some mucinous subtypes behave more aggressively. Genetic changes such as mutations in KRAS and PIK3CA are often found in more destructive tumors and may be linked with worse prognosis.

Overall, HPV associated endocervical adenocarcinoma behaves better than HPV independent adenocarcinoma, which is a different type of cervical cancer not caused by HPV.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What stage is my cancer and what does that mean for treatment?

-

What was the Silva pattern of invasion in my tumor?

-

Were lymphovascular invasion or perineural invasion present?

-

Were my surgical margins negative?

-

Did my lymph nodes show any cancer?

-

What treatment options are available for me and can I consider fertility-preserving treatment?

-

What side effects should I expect from treatment?

-

How often will I need follow-up care after treatment?