by Emily Goebel, MD FRCPC

October 9, 2025

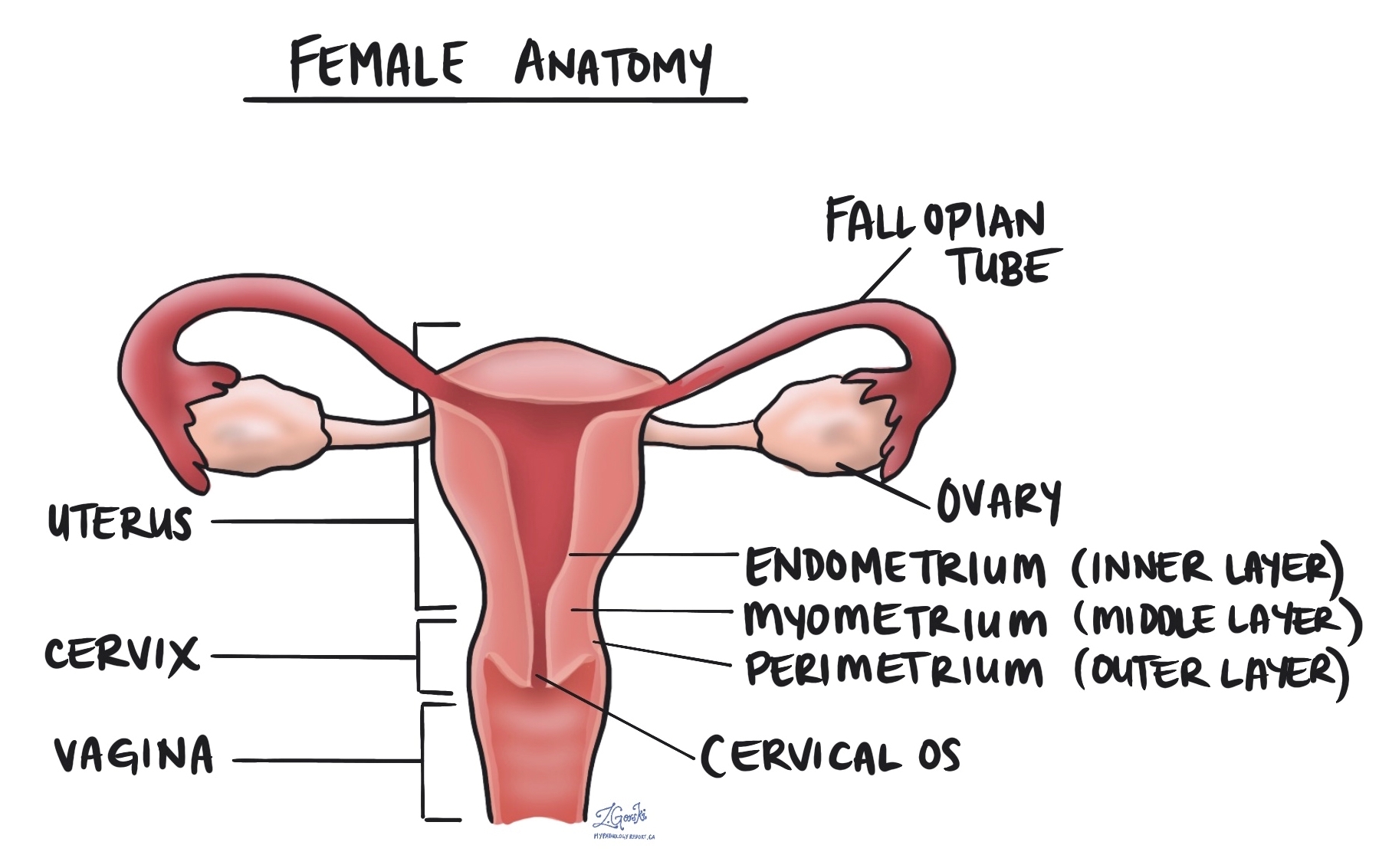

Endometrial hyperplasia without atypia is a noncancerous condition in which the lining of the uterus (called the endometrium) becomes thicker than normal. This happens because the endometrial glands grow and multiply more than they should. Although this condition is not cancer, it can sometimes develop into cancer over time, especially if it is left untreated or if the hormonal imbalance that caused it continues.

The term “without atypia” means that the cells lining the glands look normal under the microscope. This is an important distinction because when atypia (abnormal cell changes) is present, the condition carries a much higher risk of turning into cancer.

What are the symptoms of endometrial hyperplasia without atypia?

The most common symptom of endometrial hyperplasia without atypia is abnormal uterine bleeding. This may include:

-

Heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding.

-

Bleeding between menstrual periods.

-

Bleeding after menopause.

Some women have irregular or unpredictable periods, while others may experience spotting or bleeding after a period of no menstruation.

What causes endometrial hyperplasia without atypia?

Endometrial hyperplasia develops when there is an imbalance between estrogen and progesterone, the two main hormones that control the growth and shedding of the endometrium during the menstrual cycle.

Normally, during the first half of the menstrual cycle (the proliferative phase), estrogen causes the endometrium to grow and thicken in preparation for a possible pregnancy. After ovulation, progesterone helps the lining mature (the secretory phase). If pregnancy does not occur, hormone levels drop and the endometrial lining is shed during menstruation.

When there is too much estrogen and not enough progesterone, the endometrium continues to grow and becomes abnormally thick. Over time, this can lead to the development of endometrial hyperplasia.

What causes high levels of estrogen?

Several conditions or situations can lead to increased or prolonged estrogen exposure, including:

-

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A common hormonal condition that prevents regular ovulation.

-

Obesity: Fat tissue can convert other hormones into estrogen, raising estrogen levels in the body.

-

Estrogen-only medications: Taking estrogen without progesterone (for example, some types of hormone replacement therapy or birth control).

-

Tamoxifen: A medication sometimes used to treat breast cancer that can mimic estrogen in the uterus.

-

Perimenopause: The years leading up to menopause, when ovulation becomes irregular and progesterone levels may drop.

How is endometrial hyperplasia without atypia diagnosed?

The diagnosis is made by a pathologist after examining a small sample of the endometrium under the microscope. This sample is usually collected using an endometrial biopsy or a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure, in which a small amount of tissue is gently scraped or suctioned from the lining of the uterus.

Under the microscope, the pathologist sees crowded endometrial glands that vary in size and shape. The glands may be closer together than normal, but the cells lining them look normal (without atypia). The overall appearance confirms the diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia without atypia and helps rule out other conditions such as atypical endometrial hyperplasia, endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia, or endometrial carcinoma.

Can endometrial hyperplasia without atypia turn into cancer?

Endometrial hyperplasia without atypia is usually a low-risk condition, but there is still a small chance that it could progress to a type of uterine cancer called endometrioid carcinoma over time.

The risk of progression is generally less than 5% over 10 years, but it may be higher in people with ongoing exposure to excess estrogen or those who do not receive treatment. Regular follow-up and treatment to restore hormonal balance can greatly reduce this risk.

What are the treatment options?

Treatment depends on the cause, the patient’s age, symptoms, and whether they wish to preserve fertility.

Common options include:

-

Progestin therapy: Progestin (a synthetic form of progesterone) can be taken as a pill or delivered directly to the uterus using a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (IUD). This helps thin the endometrial lining and restore balance between estrogen and progesterone.

-

Weight management and hormonal balance: Addressing underlying causes such as obesity or PCOS can help reduce estrogen levels and prevent recurrence.

-

Follow-up biopsy: Doctors often recommend repeating the endometrial biopsy after several months of treatment to confirm that the lining has returned to normal.

In most cases, medical treatment is successful and surgery is not needed. However, if the condition persists despite therapy or if atypia develops, a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) may be considered, particularly in postmenopausal patients.

What is the prognosis for endometrial hyperplasia without atypia?

The prognosis is excellent. Most patients respond well to hormonal treatment, and the endometrium usually returns to normal within several months. Regular follow-up with your doctor and repeat biopsies are important to ensure that the abnormal thickening has resolved and that no new changes have developed.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What type of endometrial hyperplasia do I have?

-

What caused my endometrial lining to become thickened?

-

What treatment options are best for me?

-

Will I need follow-up biopsies or imaging?

-

How likely is this condition to come back or turn into cancer?

-

Should I be concerned about my hormone levels or other risk factors?