by Rosemarie Tremblay-LeMay MD FRCPC

August 18, 2025

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a group of diseases that affect the bone marrow, which is the spongy tissue inside bones where new blood cells are made. In MDS, the bone marrow produces abnormal blood cells that do not function properly. Because of this, people with MDS often have low numbers of healthy blood cells.

MDS also increases the risk of developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a type of blood cancer. Not every person with MDS will develop AML, but the risk is higher than in the general population.

What cells are normally found in the blood?

Normal blood contains several types of cells, each with an important role:

-

Red blood cells (RBCs) carry oxygen from the lungs to the body and return carbon dioxide to the lungs to be exhaled.

-

White blood cells (WBCs) are part of the immune system. Types include neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes, which fight infections and help the body heal.

-

Platelets help stop bleeding by forming blood clots after an injury.

These cells are made in the bone marrow through a process called hematopoiesis. Diseases like MDS damage this process, which leads to fewer healthy cells being produced.

What medical conditions are associated with MDS?

The symptoms and complications of MDS depend on which blood cells are low or abnormal:

-

Anemia occurs when there are too few red blood cells. People with anemia may feel tired, weak, short of breath, or experience chest pain.

-

Neutropenia occurs when neutrophils are low. This makes infections more likely and sometimes more severe.

-

Thrombocytopenia occurs when platelet counts are low. This increases the risk of bruising, bleeding after an injury, or spontaneous bleeding.

-

Pancytopenia is when all three blood cell types (red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets) are reduced. This can cause a combination of the symptoms listed above.

What causes myelodysplastic syndrome?

MDS starts when a genetic change develops in an immature bone marrow cell. This change is not usually inherited but happens during a person’s life. As the abnormal cell multiplies, it creates more cells with the same change. Over time, these abnormal cells replace healthy ones in the bone marrow.

As MDS progresses, new genetic changes may appear, making the disease more aggressive or more likely to transform into acute myeloid leukemia.

How is the diagnosis of MDS made?

MDS is usually diagnosed after a bone marrow biopsy and aspiration, a procedure where a small sample of bone marrow is removed and examined under a microscope by a pathologist.

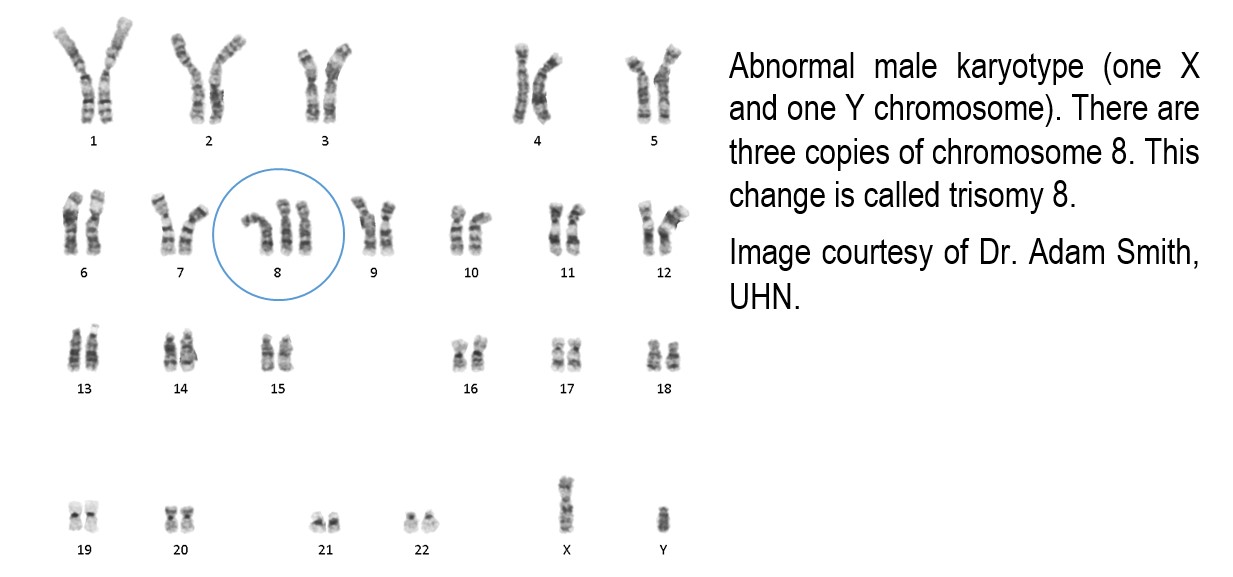

Additional tests, such as a karyotype, may be performed to look for genetic changes in the chromosomes. In some cases, next-generation sequencing (NGS) is used to detect smaller genetic mutations that cannot be seen on a karyotype. These genetic results help classify MDS and guide treatment decisions.

Microscopic features of MDS

When examining the bone marrow, the pathologist looks for abnormal development of blood cells. If cells appear abnormal in shape, size, or color, this is called dysplasia.

-

Single-lineage dysplasia means only one type of blood cell looks abnormal.

-

Multilineage dysplasia means two or more types of blood cells look abnormal.

To diagnose MDS, at least 10% of the cells in a given cell line must show dysplasia.

What is a karyotype and why is it important?

A karyotype is a test that examines chromosomes (the structures in cells that hold DNA). Abnormalities may include missing or extra chromosomes, broken pieces, or sections swapped between chromosomes.

-

Some abnormalities are linked with a better prognosis and treatment response.

-

Others suggest a worse outcome or greater chance of progression to acute leukemia.

When three or more abnormalities are found, this is called a complex karyotype and usually indicates a more aggressive disease.

Because these changes provide valuable information about prognosis and treatment, the karyotype is an essential part of evaluating MDS.

Types of myelodysplastic syndromes

Doctors classify MDS into different types based on which cells are abnormal, how many blasts (immature cells) are present, and which genetic changes are found.

The types of MDS include:

-

MDS with single lineage dysplasia.

-

MDS with multilineage dysplasia.

-

MDS with ring sideroblasts.

-

MDS with excess blasts.

-

MDS with isolated deletion of chromosome 5q.

MDS that develops after chemotherapy or radiation therapy is classified as therapy-related myeloid neoplasm, which is considered separately because it often behaves more aggressively.

Are some forms of MDS inherited?

Most people who develop MDS do not have an inherited risk. These cases are called sporadic.

Rarely, some people inherit genetic changes (called germline mutations) that increase the risk of developing MDS or other bone marrow diseases. If other family members have been diagnosed with similar conditions or persistent low blood counts, your doctor may recommend genetic testing to see if an inherited mutation is present.

What are ring sideroblasts?

Ring sideroblasts are immature red blood cells that contain too much iron. The iron forms a ring around the nucleus (the control center of the cell).

The diagnosis of MDS with ring sideroblasts is made if more than 15% of immature red cells in the bone marrow show this ring pattern. In some cases, the diagnosis can be made if at least 5% of these cells are ring sideroblasts and the patient has a mutation in a gene called SF3B1.

Other causes of ring sideroblasts, such as copper deficiency, medications, or toxins, must be ruled out before confirming MDS.

What does MDS with excess blasts mean?

Blasts are very immature cells in the bone marrow that develop into mature blood cells. In MDS, too many blasts are a sign that the disease may be progressing toward acute leukemia.

-

MDS-EB1 is diagnosed when 2–4% of blasts are seen in the blood or 5–9% in the bone marrow.

-

MDS-EB2 is diagnosed when 5–19% of blasts are seen in the blood or 10–19% in the bone marrow, or if the blasts contain structures called Auer rods.

If blasts make up 20% or more of the cells, the diagnosis changes from MDS to acute myeloid leukemia.

Other conditions that can look like MDS

Several other conditions can cause abnormal-looking blood cells or low blood counts, including vitamin B12 or copper deficiency, certain medications, alcohol use, heavy metal poisoning, infections, and autoimmune diseases. Other bone marrow cancers, such as chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, may also resemble MDS. Your doctor will carefully review your history and test results to rule out these possibilities.

Questions to ask your doctor

If you have been diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome, you may wish to ask your doctor the following questions:

-

What type of MDS do I have?

-

What do my genetic test results show, and how do they affect my prognosis?

-

Do I have excess blasts, and what does that mean for my risk of developing acute leukemia?

-

What treatment options are available for me, and what are their potential benefits and side effects?

-

Should my family members be tested for inherited conditions related to MDS?