by Emily Goebel, MD FRCPC

September 5, 2025

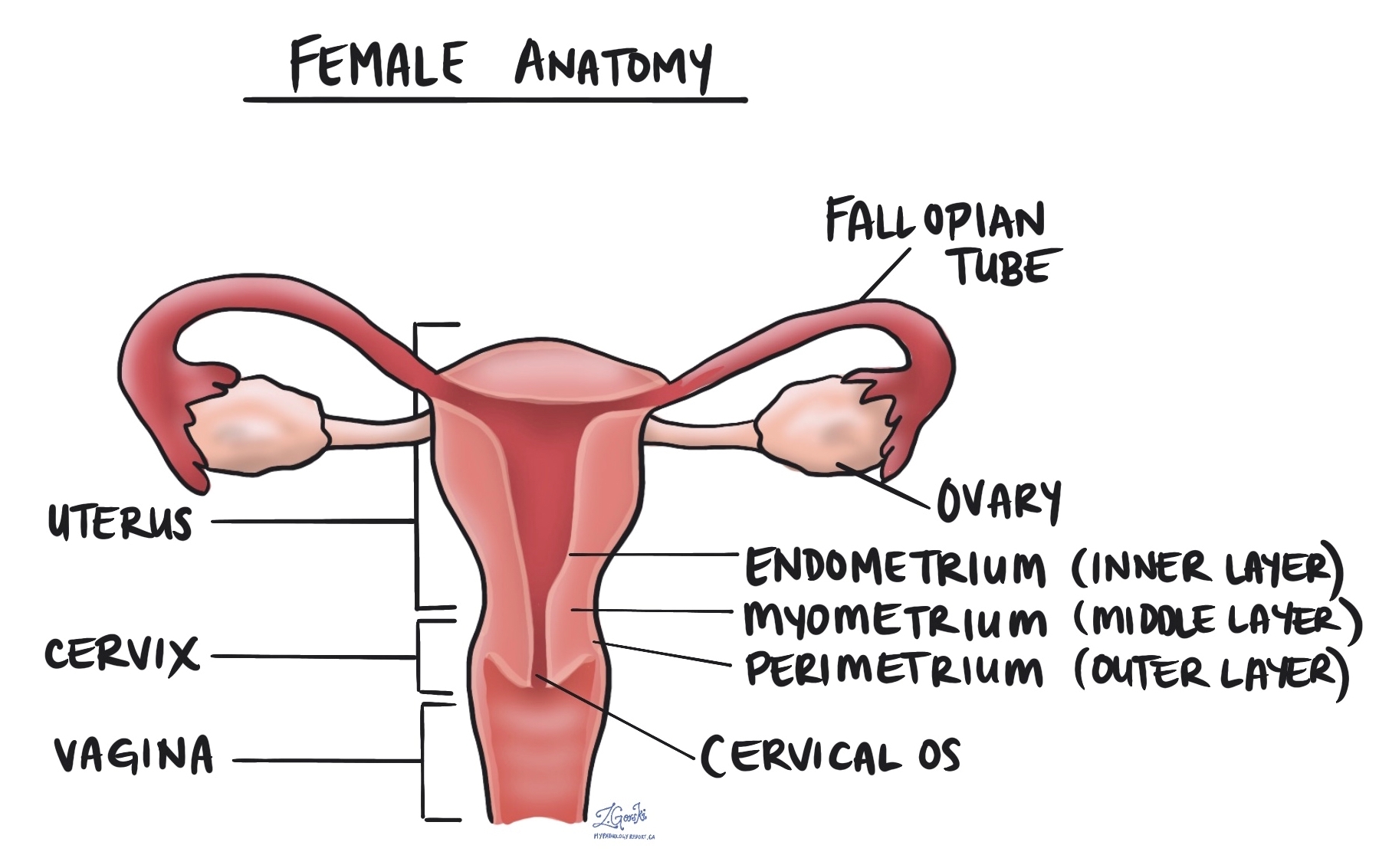

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH) is a precancerous condition of the lining of the uterus, called the endometrium. In AEH, the endometrium becomes abnormally thick and the glandular cells that make up the endometrium start to grow in a crowded and irregular pattern. The cells also look abnormal under the microscope, which is why the word atypical is used.

Another name for this condition is endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN). AEH is important to recognize because it can progress to a type of endometrial cancer called endometrioid adenocarcinoma if it is not treated.

Does atypical endometrial hyperplasia mean cancer?

No. AEH is not cancer. However, it is considered precancerous because there is a significant risk that it will turn into endometrial cancer over time if left untreated. For this reason, treatment is usually recommended once the diagnosis is confirmed.

What are the symptoms of atypical endometrial hyperplasia?

The most common symptom of AEH is abnormal uterine bleeding.

This may include:

-

Heavy menstrual bleeding.

-

Bleeding between periods.

-

Bleeding after menopause.

Because abnormal bleeding can have many causes, further testing such as an endometrial biopsy is often performed to confirm the diagnosis.

How does atypical endometrial hyperplasia develop?

The growth of the endometrium is controlled by the hormones estrogen and progesterone, which are produced by the ovaries during the menstrual cycle.

-

In the first half of the cycle, estrogen stimulates the endometrium to grow and thicken in preparation for a possible pregnancy.

-

After ovulation, progesterone balances the effect of estrogen by helping the endometrium mature. If pregnancy does not occur, hormone levels drop, and the endometrium sheds during menstruation.

AEH develops when there is too much estrogen and not enough progesterone. Without the balancing effect of progesterone, the endometrium continues to grow and becomes abnormally thick. Over time, this imbalance can cause the cells lining the endometrial glands to look abnormal and precancerous.

What causes increased estrogen?

Several situations can lead to increased or prolonged estrogen exposure, including:

-

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

-

Obesity, because fat tissue can produce estrogen.

-

Estrogen-only hormone therapy or birth control.

-

Tamoxifen treatment, a medication used for breast cancer.

-

Perimenopause, when hormone levels fluctuate and estrogen may remain unopposed by progesterone.

These factors do not always lead to AEH, but they increase the risk of its development.

How is the diagnosis made?

The diagnosis is made after tissue from the endometrium is sampled and examined under the microscope.

-

An endometrial biopsy removes a small piece of tissue using a thin instrument passed through the cervix.

-

A dilation and curettage (D&C) scrapes tissue from the lining of the uterus using a spoon-shaped instrument.

The sample is sent to a pathologist, who examines it under the microscope and describes the changes in a pathology report.

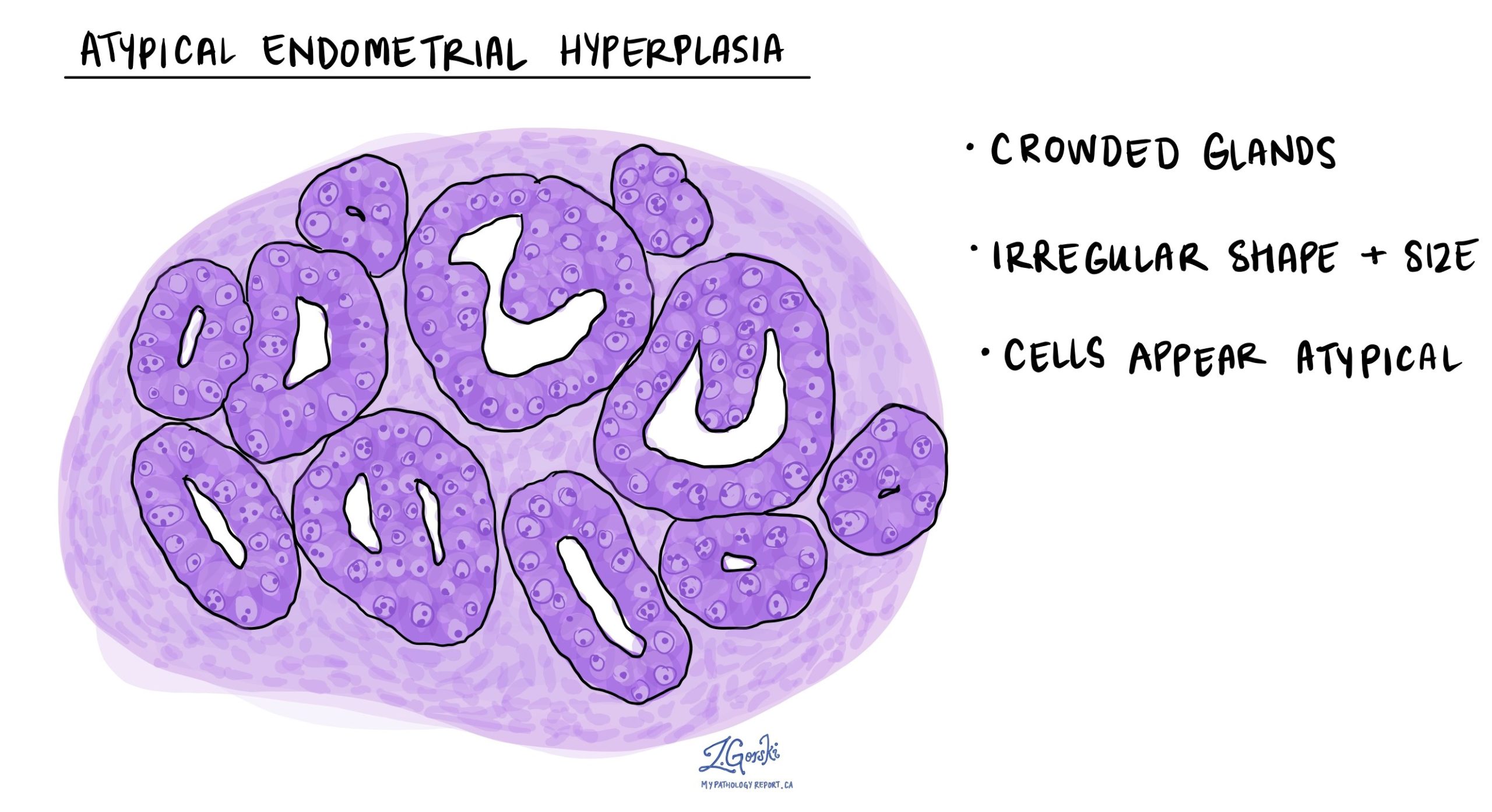

What does atypical endometrial hyperplasia look like under the microscope?

When viewed under the microscope, AEH shows:

-

Crowded and irregular endometrial glands, which are more numerous and complex than normal glands.

-

Atypical glandular cells, which means the cells lining the glands look different from those in a healthy endometrium. The nuclei of these cells may be larger, darker, or irregular in shape.

These changes are different from simple thickening of the endometrium without atypia and are important because they carry a much higher risk of progression to cancer.

What are the treatment options for atypical endometrial hyperplasia?

Because AEH carries a significant risk of developing into cancer, treatment is recommended for most patients.

Options include:

-

Hysterectomy: Surgical removal of the uterus, often along with the fallopian tubes and ovaries. This is the most definitive treatment and eliminates the risk of progression.

-

Hormonal therapy: For women who still want to have children or who cannot undergo surgery, an intrauterine device (IUD) that releases progesterone or high-dose progesterone medication may be used. Hormone therapy can cause the abnormal cells to regress, but careful monitoring with repeat biopsies is required.

Your doctor will discuss the best option based on your age, medical history, and whether you wish to preserve fertility.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

How severe are the changes in my endometrium?

-

Do I need surgery, or could hormonal treatment be an option for me?

-

What is my risk of this condition turning into cancer?

-

How often will I need follow-up testing if I do not have surgery right away?

-

If I choose hormonal therapy, how will we monitor whether it is working?