by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

September 14, 2025

Actinic keratosis (AK) is a pre-cancerous skin condition caused by long-term damage from ultraviolet (UV) radiation. It is considered pre-cancerous because, over time, some actinic keratoses can progress into a type of skin cancer called squamous cell carcinoma.

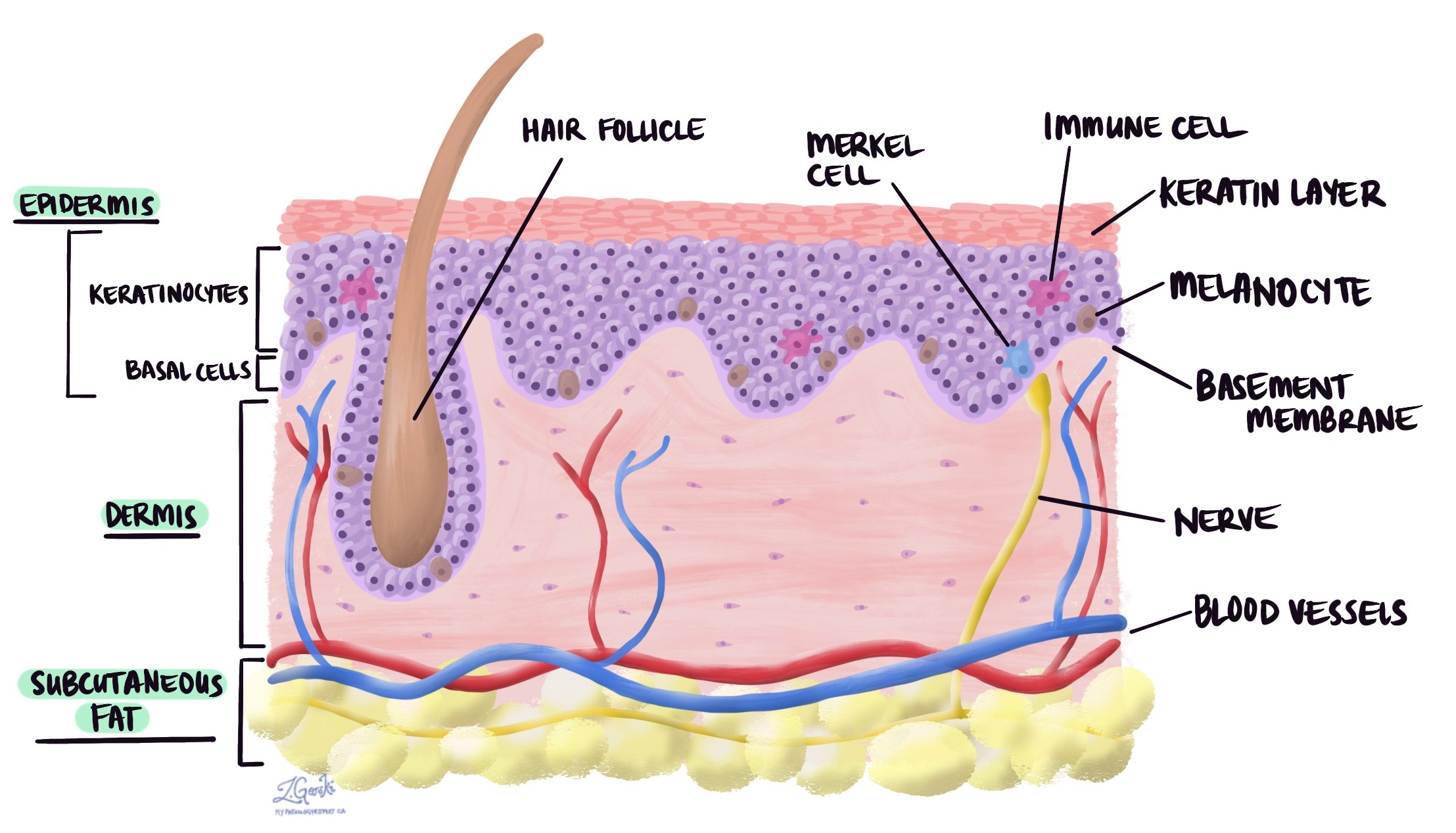

Actinic keratosis is made up of abnormal skin cells called keratinocytes, which are found in the top layer of the skin, called the epidermis.

When actinic keratosis develops on the lips, it is called actinic cheilitis.

What are the symptoms of actinic keratosis?

Actinic keratosis usually appears as rough, scaly patches of skin that feel like sandpaper. These patches are often easier to feel than to see.

Symptoms can include:

-

Small patches that are red, pink, or skin-coloured.

-

Roughness, dryness, or scaling.

-

Itching, burning, or mild tenderness.

-

Lesions that are flat, raised, or form thick crusts.

Actinic keratoses most often develop on sun-exposed areas of the body, such as the:

-

Face.

-

Scalp (especially in bald men).

-

Lips.

-

Ears.

-

Hands and forearms.

-

Lower legs.

It is common for people to develop multiple actinic keratoses at the same time.

What causes actinic keratosis?

The main cause of actinic keratosis is chronic sun exposure. Over time, ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun damages the DNA of skin cells, causing them to grow abnormally.

Risk factors include:

-

Older age – the longer you live, the more sun exposure accumulates.

-

Fair skin that burns easily.

-

Outdoor lifestyle or work with frequent sun exposure.

-

History of sunburns or tanning bed use.

-

Weakened immune system, such as after an organ transplant or from certain medications.

How is this diagnosis made?

Doctors often suspect actinic keratosis based on how the lesion looks and feels during a skin exam. Because actinic keratosis can resemble other skin conditions (like eczema, psoriasis, or seborrheic keratosis), a biopsy may be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

During a biopsy, a small piece of the lesion is removed and examined under a microscope by a pathologist. This allows the pathologist to confirm the presence of abnormal keratinocytes and to rule out squamous cell carcinoma.

What does actinic keratosis look like under the microscope?

When viewed under the microscope, actinic keratosis shows several important features:

-

Abnormal keratinocytes (skin cells) with irregular size and shape that replace the normal cells of the epidermis.

-

Parakeratosis (retained nuclei in the surface layer), showing that the skin’s natural shedding process is disrupted.

-

Hyperkeratosis (thickened surface layer) in some areas.

-

Solar elastosis (damaged elastic tissue in the dermis), a sign of long-term sun damage.

-

Inflammatory cells and tiny new blood vessels beneath the epidermis, reflecting the body’s response to injury.

These microscopic features confirm the diagnosis and highlight the link between actinic keratosis and sun-induced skin damage.

Variants of actinic keratosis

Actinic keratosis can appear in different forms, called variants. Some variants carry a higher risk of progressing into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

-

Classic actinic keratosis – The most common type, appearing as rough, scaly patches. The risk of progression is low but increases if there are multiple lesions or if they are left untreated.

-

Atrophic actinic keratosis – Appears thin and flat, often without the protective keratin layer. Despite looking less severe, these lesions can still progress to invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

-

Pigmented actinic keratosis – Contains pigment (melanin), making it appear brown. It may resemble melanoma or other pigmented lesions. The pigmentation itself does not increase the cancer risk, but it can delay diagnosis.

-

Lichenoid actinic keratosis – Shows a strong inflammatory reaction that resembles lichen planus. The inflammation may increase the risk of malignant transformation.

-

Bowenoid actinic keratosis – Looks very similar under the microscope to squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease). This type has a high risk of progressing to invasive squamous cell carcinoma and requires prompt treatment.

-

Acantholytic actinic keratosis – Shows loss of adhesion between cells, creating spaces or clefts. Its risk of progression is not fully understood, but it may signal more aggressive local growth.

-

Hypertrophic actinic keratosis – Appears thick and crusted. This type may be harder to treat and carries a higher risk of progression if persistent or recurrent.

What is the risk of developing invasive squamous cell carcinoma?

Although most actinic keratoses remain stable or regress, a small percentage progress into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

-

The overall risk is estimated to be less than 10% per lesion, but the risk increases if a person has many lesions, leaves them untreated, or has a weakened immune system.

-

Variants such as bowenoid and hypertrophic AK carry a higher risk of malignant transformation.

Because actinic keratosis is considered a marker of chronic sun damage, the presence of AKs also indicates a higher risk of developing other skin cancers, including basal cell carcinoma and melanoma.

What is the difference between squamous cell carcinoma in situ and actinic keratosis?

Actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma in situ are related but different conditions:

-

In actinic keratosis, the abnormal squamous cells are limited to the bottom part of the epidermis. It is considered a precancerous lesion, meaning it has the potential to become cancer but is not yet a full skin cancer.

-

In squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease), the abnormal cells replace the entire thickness of the epidermis. At this point, it is considered an early stage of skin cancer.

Both conditions can progress to invasive squamous cell carcinoma if left untreated, but the risk is higher for squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

Because these conditions can look similar, a biopsy and microscopic examination are often needed to tell them apart.

Questions to ask your doctor

- Do I need treatment, or can this lesion just be monitored?

-

What treatment options are available (cryotherapy, topical creams, photodynamic therapy, excision)?

-

What is my risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma?

-

How can I prevent new actinic keratoses from forming?

-

How often should I have skin checks after this diagnosis?