by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Md Shahrier Amin, M.B.B.S., Ph.D.

May 31, 2025

Acute T cell-mediated rejection, also known as acute cellular rejection, is a condition in which the body’s immune system attacks the transplanted kidney. This occurs because special immune cells, called T cells, mistakenly identify the transplanted organ as harmful or foreign. When this happens, the T cells enter the kidney tissue, leading to inflammation and damage to the kidney’s structure. If this rejection is identified early, it can usually be treated successfully.

What causes acute T cell-mediated rejection?

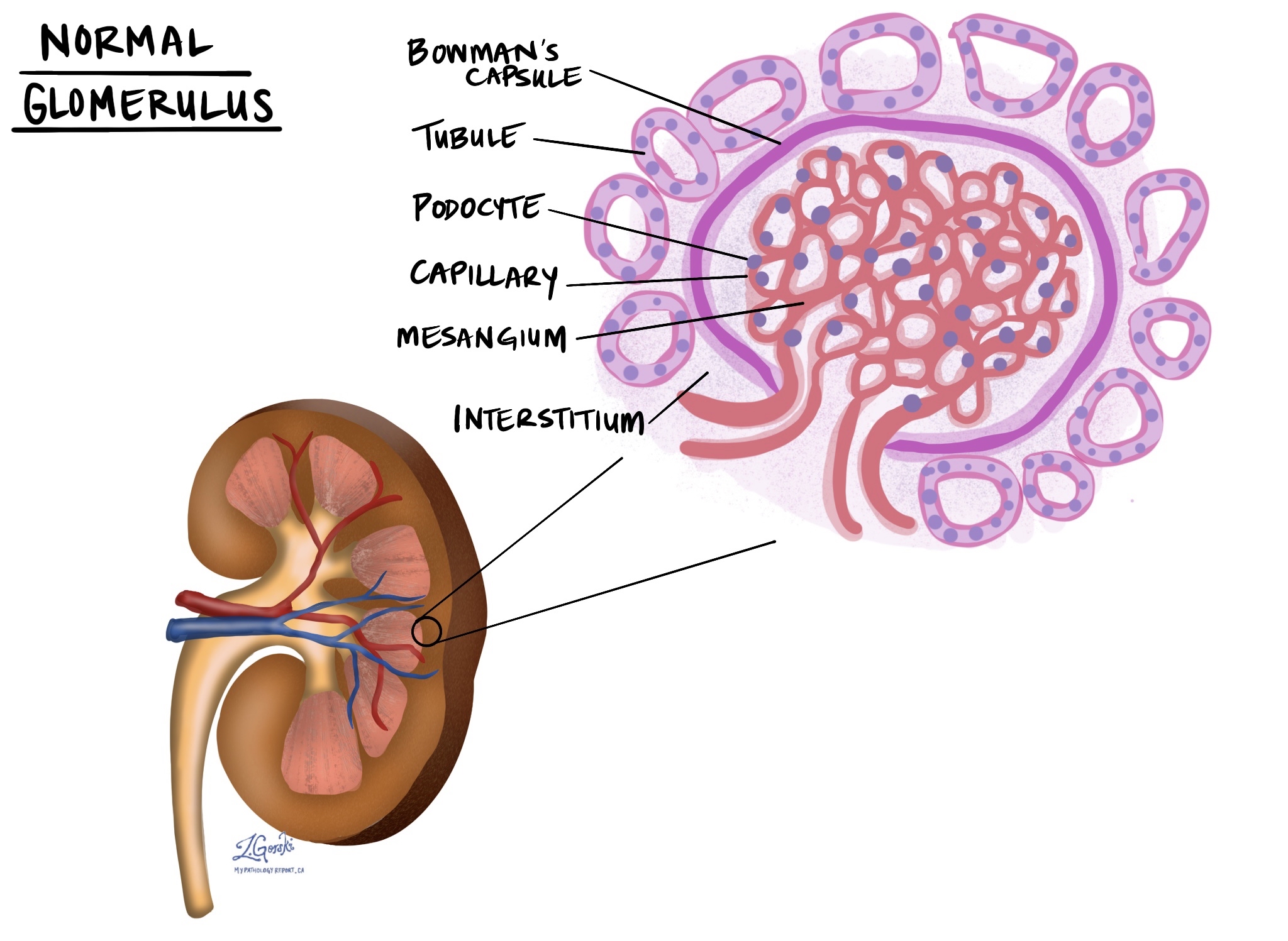

Acute T cell-mediated rejection happens because your immune system recognizes proteins (called HLA antigens) on the transplanted kidney as different or unfamiliar. This triggers T cells to directly attack the kidney cells, damaging important parts of the kidney, including the small tubes (tubules), the tissue surrounding the tubes (interstitium), blood vessels, and sometimes other structures, such as the glomeruli (the filtering units). This type of rejection can occur at any time after the transplant, from a few days to several years later.

What are the symptoms of acute T cell-mediated rejection?

Symptoms of acute rejection often include:

-

Decreased urine output.

-

Swelling or tenderness around the transplant area.

-

Sudden increase in blood creatinine (a test indicating kidney injury).

-

High blood pressure.

-

Swelling (fluid retention).

-

Protein in the urine (proteinuria).

Some people may experience mild symptoms, while others may have more severe changes, depending on how aggressively their immune system responds.

How is this diagnosis made?

Acute T cell-mediated rejection is typically diagnosed by examining a biopsy from the transplanted kidney. A biopsy involves taking a small tissue sample, which is then examined by a pathologist under a microscope. The pathologist looks carefully for inflammation and damage caused by T cells. Special stains and additional tests help confirm the diagnosis.

What is the Banff score and how is it determined?

The Banff score is a system pathologists use to grade the severity of acute rejection.

The Banff classification uses two main factors:

-

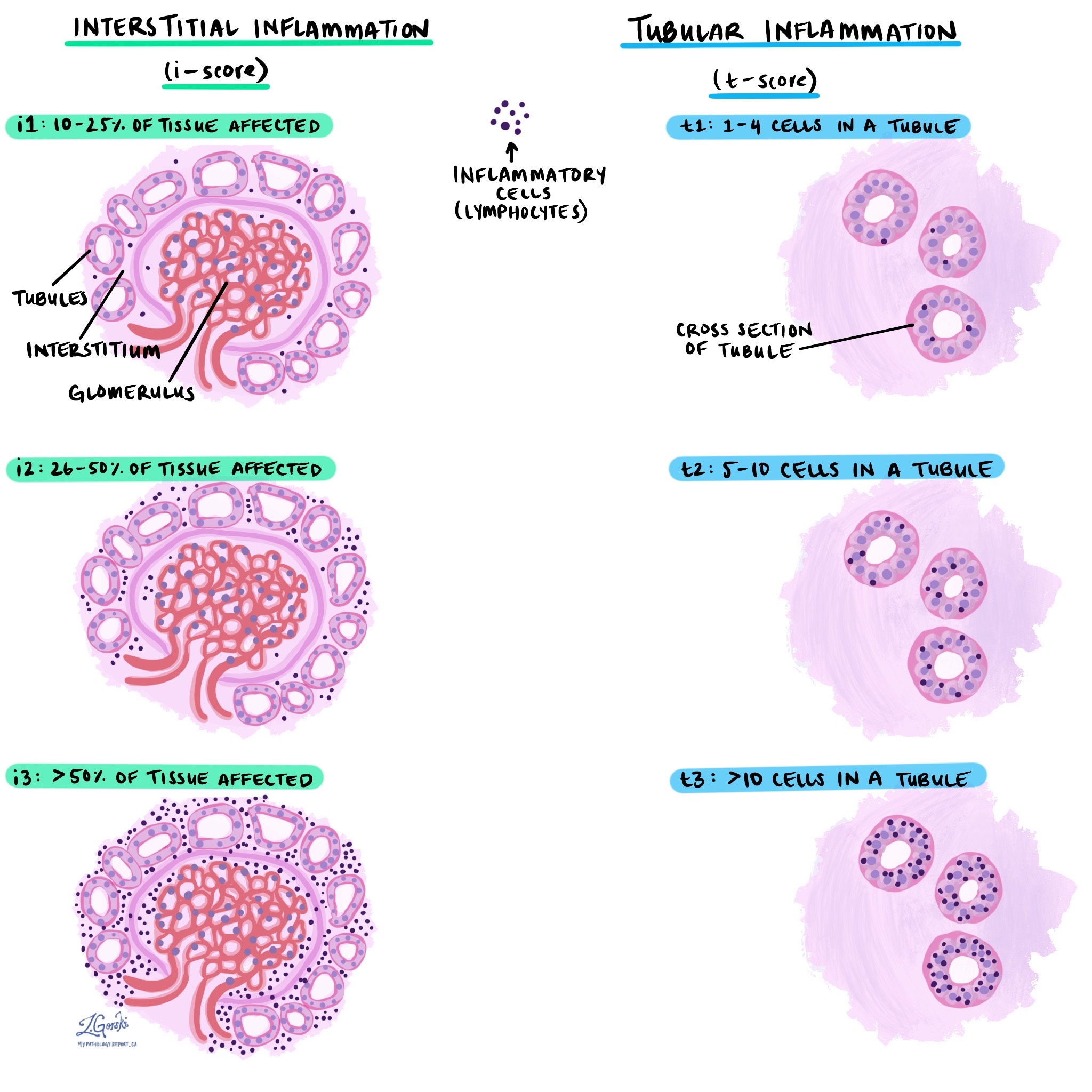

Interstitial inflammation (i-score): This is the percentage of kidney tissue affected by inflammation.

-

i1: 10-25% of tissue affected.

-

i2: 26-50% of tissue affected.

-

i3: more than 50% of tissue affected.

-

-

Tubulitis (t-score): This component describes how many immune cells are attacking each kidney tubule (small tube structure).

-

t1: 1 to 4 cells in a tubule.

-

t2: 5 to 10 cells in a tubule.

-

t3: more than 10 cells in a tubule.

-

These two features are combined to classify the severity:

-

Type IA: Moderate tubulitis (t2) and significant inflammation (i2 or i3).

-

Type IB: Severe tubulitis (t3) and significant inflammation (i2 or i3).

-

Type IIA: Mild blood vessel inflammation (intimal arteritis or endothelialitis) affecting less than 25% of the vessel wall.

-

Type IIB: More severe vessel inflammation, affecting at least 25% of the vessel wall.

-

Type III: Severe inflammation involving the full thickness of the blood vessel wall, sometimes with severe damage and necrosis (cell death).

Higher scores indicate more severe rejection, which requires stronger treatment.

What other features do pathologists look for when making this diagnosis?

Interstitial inflammation

Interstitial inflammation refers to the buildup of immune cells within the tissue that surrounds the kidney’s small tubes (called tubules). Normally, this area (called the interstitium) provides structural support and contains tiny blood vessels that deliver oxygen and nutrients to the kidney. In acute T cell-mediated rejection, immune cells, such as T cells, accumulate in this area, causing swelling and irritation. Pathologists carefully examine the extent of this inflammation, as greater involvement of the interstitium suggests more severe rejection.

Tubulitis

Tubulitis describes inflammation within the kidney’s tubules, which are small, tube-shaped structures responsible for filtering and transporting fluid and waste products. In tubulitis, immune cells (usually T cells) invade these tubes, directly damaging their lining. This interferes with the kidneys’ ability to filter and manage fluids properly. Pathologists count the number of immune cells attacking each tubule—more immune cells per tubule typically indicate more severe damage and a stronger immune reaction.

Tubular injury

Tubular injury refers specifically to direct damage to the cells lining the kidney tubules. When the tubules become inflamed due to rejection, the lining cells can become injured or even die. Injured tubules cannot properly filter waste and maintain the body’s fluid and electrolyte balance. Signs of tubular injury include cell swelling, loss of normal structure, and areas where cells have died and detached from the tubular wall. The severity of tubular injury helps pathologists gauge how much immediate damage the rejection has caused to the kidney.

Microvascular inflammation and microangiopathic changes

Microvascular inflammation refers to inflammation affecting the tiny blood vessels (capillaries) within the kidney. These tiny vessels are essential for providing blood, oxygen, and nutrients to the kidney’s filtering units. In acute rejection, immune cells can attack the lining of these tiny blood vessels, causing damage and restricting normal blood flow.

Microangiopathic changes refer to additional damage to small blood vessels, which can include narrowing, blockage, or breakdown of vessel walls. Such changes can interfere with blood flow and may lead to additional damage or even tissue death due to inadequate blood supply. The extent of microvascular inflammation and these small blood vessel changes helps the pathologist and doctor understand how much the rejection process is harming the kidney’s ability to function normally.

Glomerulosclerosis

Glomerulosclerosis refers to scarring of the kidney’s glomeruli, the tiny structures that filter waste from the blood. This scarring occurs when glomeruli are damaged over time, typically due to repeated inflammation or immune-mediated attacks. When pathologists describe glomerulosclerosis, they use terms such as “global” or “segmental.” Global means the entire glomerulus is scarred, while segmental means only part of a glomerulus is scarred. The amount and type of glomerulosclerosis can help your doctor understand how severely your kidneys have been affected by rejection and chronic injury.

Common tests to confirm the diagnosis

Pathologists use several specialized tests to examine your kidney biopsy and confirm a diagnosis of acute T cell-mediated rejection. Each test provides different but complementary information.

Light microscopy

In this test, your kidney biopsy sample is carefully sliced into extremely thin sections and stained with special dyes. These dyes highlight different parts of kidney tissue, allowing the pathologist to examine cells, tubules, blood vessels, and glomeruli under a standard microscope. Light microscopy reveals the presence and extent of inflammation, the number and location of immune cells, as well as specific features such as tubulitis (inflammation within tubules) and interstitial inflammation.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence is a specialized test that uses antibodies tagged with fluorescent dyes to detect specific proteins or immune substances within your kidney tissue. During this test, the pathologist applies these fluorescent antibodies directly to thin slices of your kidney biopsy and then views them under a microscope with ultraviolet light. In acute T cell-mediated rejection, the immunofluorescence test is often negative for certain markers, such as C4d, which helps distinguish it from other forms of rejection (like antibody-mediated rejection, where C4d is usually positive).

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy is an advanced technique that enables pathologists to visualize extremely small details within kidney cells. Your biopsy tissue is cut into ultra-thin slices and placed under a powerful microscope (electron microscope) that can show structures thousands of times smaller than those visible under a regular microscope. Although electron microscopy does not reveal specific changes unique to acute T cell-mediated rejection, it can help rule out other conditions, such as certain infections or specific types of kidney diseases, by providing detailed images of cellular structures.

What is the difference between acute rejection and chronic rejection?

Acute rejection usually happens quickly after transplantation (within days, weeks, or months) and involves a sudden, strong immune response. It can usually be treated effectively with adjustments to immunosuppressive medications.

Chronic rejection develops slowly over months or years and involves gradual scarring and long-term injury to the kidney. It is more difficult to treat, may progress even with medication, and often leads to gradual loss of kidney function.

What is the difference between acute T cell-mediated rejection and antibody-mediated rejection?

Both acute T cell-mediated rejection and antibody-mediated rejection involve your immune system attacking the transplanted kidney, but they do so in different ways.

In acute T-cell-mediated rejection, the damage is caused directly by specialized immune cells known as T cells. These T cells enter the kidney tissue and attack cells they see as foreign, causing inflammation and tissue injury, primarily affecting the tubules, interstitium (supporting tissue around the tubules), and small blood vessels.

In contrast, antibody-mediated rejection is caused by special proteins called antibodies, produced by a different part of your immune system. These antibodies bind to specific targets on the kidney, triggering inflammation and injury mainly in the blood vessels of the kidney. Pathologists can detect antibody-mediated rejection by special tests, such as C4d staining, which highlights antibody-related injury in tiny kidney blood vessels.

Sometimes both types of rejection can occur simultaneously, causing more severe damage. Identifying which type (or types) of rejection is present is essential because each requires a different treatment approach.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

How severe is my rejection episode, according to my biopsy results?

-

Which type of T cell-mediated rejection do I have?

-

Will I need changes to my medication to treat this rejection?

-

How quickly can we expect my kidney function to improve after treatment?

-

Do I need any follow-up tests or biopsies to monitor this rejection?

-

Are there any specific symptoms I should watch for at home?

-

Is my current rejection episode likely to affect my kidneys’ long-term health?

-

How can we prevent future episodes of acute rejection?

-

Am I at risk for developing chronic rejection?

-

Should I consult with a kidney transplant specialist?