by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

February 9, 2023

What is ameloblastoma?

Ameloblastoma is a non-cancerous type of bone tumour. Ameloblastoma is called an odontogenic tumour because it starts from cells normally involved in the development of the teeth (“odonto” means “teeth” and “genic” means “producing”). These tumours tend to grow slowly over time. Large tumours can cause pain, swelling, loose teeth, and facial deformity.

Where does ameloblastoma start?

Most ameloblastomas start in the jaw. The jaw is made up of two bones, the mandible (lower jaw) and the maxilla (upper jaw). The bones of the jaw are different from other bones in the body because create and support teeth. Human teeth develop within the mandible and maxilla before birth (in utero) although they do not become visible for months or even years after birth. Each tooth develops from a structure called the tooth bud. Within the tooth bud are specialized cells called ameloblasts which produce enamel, a hard substance that gives teeth their strength. Ameloblastoma starts from ameloblasts that remain in the jaw after birth.

What are the symptoms of ameloblastoma?

Small ameloblastomas typically do not cause any symptoms. However, as the tumour grows it can cause teeth to move and weaken the surrounding bone. If left untreated, large tumours can cause the bone to break.

What causes ameloblastoma?

At the present time, the causes of ameloblastoma remain unknown.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis can be made after part or all of the tumour is surgically removed and sent to a pathologist for examination under a microscope.

What are the types of ameloblastoma?

Pathologists divide ameloblastoma into different groups called types or variants based on how the tumour looks when examined under the microscope. Types of ameloblastoma include follicular, plexiform, desmoplastic, and acanthomatous. All types of ameloblastoma are non-cancerous tumours that are unlikely to grow back if fully removed.

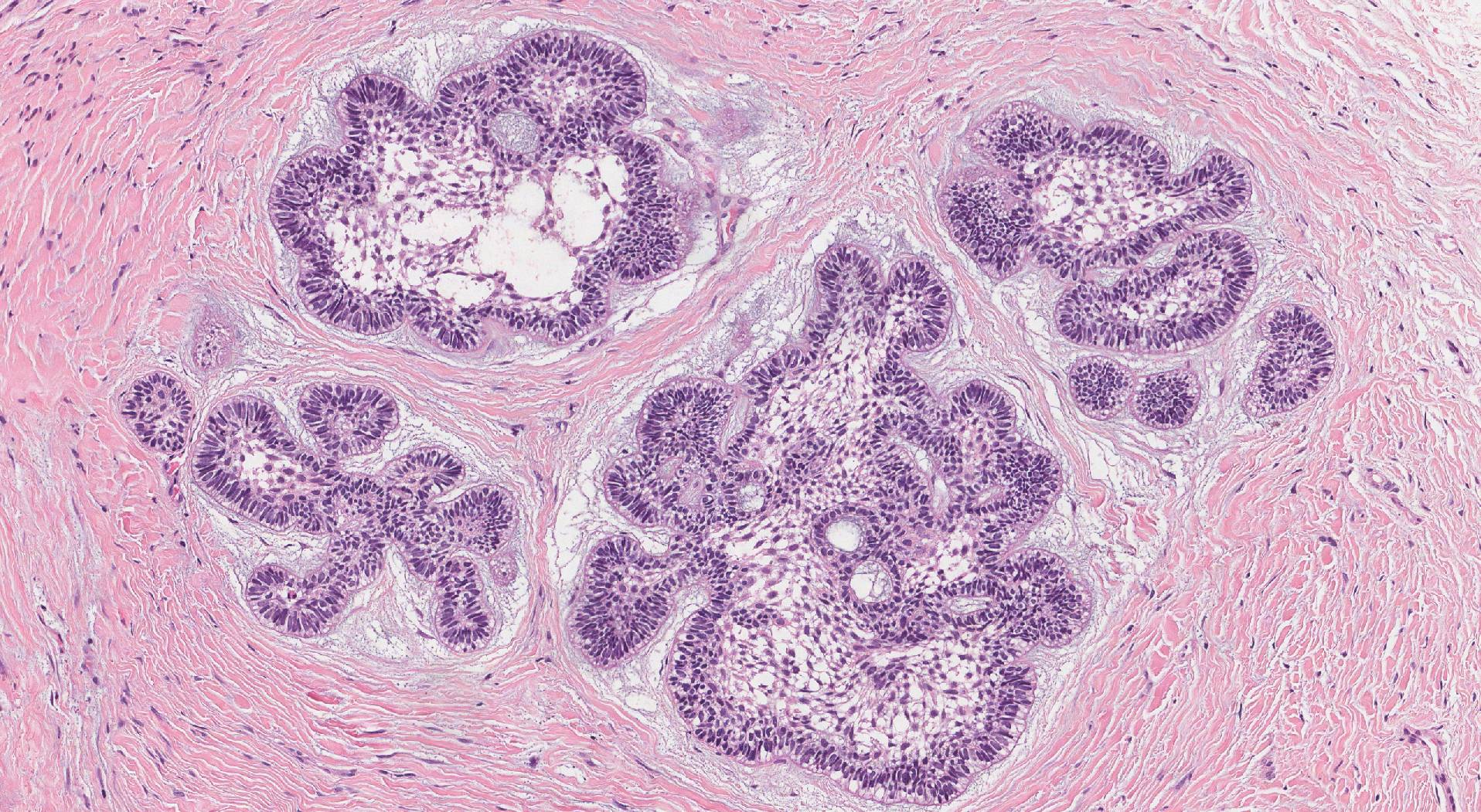

Follicular ameloblastoma

Follicular type ameloblastoma is the most common type of ameloblastoma. It is made up of large groups of tumour cells that look similar to the ameloblasts in the developing tooth. The tumour cells at the edge or periphery of the groups tend to line up side-by-side in a pattern that pathologists describe as palisading. The nucleus of the cell may also be located in an unusual location away from the bottom of the cell. These cells are described as having ‘reverse polarity’ because the normal location of the nucleus or ‘normal polarity’ is near the bottom of the cell. Finally, the cells in the centre of the group are long and thin and surrounded by loose connective tissue. These cells look similar to cells called the stellate reticulum which is normally found in the developing tooth.

Plexiform ameloblastoma

Plexiform type ameloblastoma is the second most common type of ameloblastoma. The tumour cells in the plexiform type look similar to ameloblasts in the developing tooth and are connected together to form long chains of cells. The chains of cells typically connect together in a pattern pathologists describe as ‘anastomosing’.

Desmoplastic ameloblastoma

Desmoplastic type ameloblastoma is a rare type of ameloblastoma. Compared to the follicular and plexiform types, the tumour cells in the desmoplastic type look less similar to the ameloblasts in the developing tooth. The tumour cells are often found in groups and the cells at the edge of the group are square-shaped or flat. The tumour cells in the centre of the group are long and thin and surrounded by loose connective tissue. These cells look similar to cells called the stellate reticulum which is normally found in the developing tooth. The groups of tumour cells are surrounded by dark pink connective tissue. Pathologists describe this connective tissue as fibrotic or hyalinized.

Acanthomatous ameloblastoma

Acanthomatous type ameloblastoma is a rare type of ameloblastoma. The tumour cells in this type are larger and pinker than the tumour cells in the other types of ameloblastoma and they look similar to specialized squamous cells that are normally found in other areas of the body such as the skin.

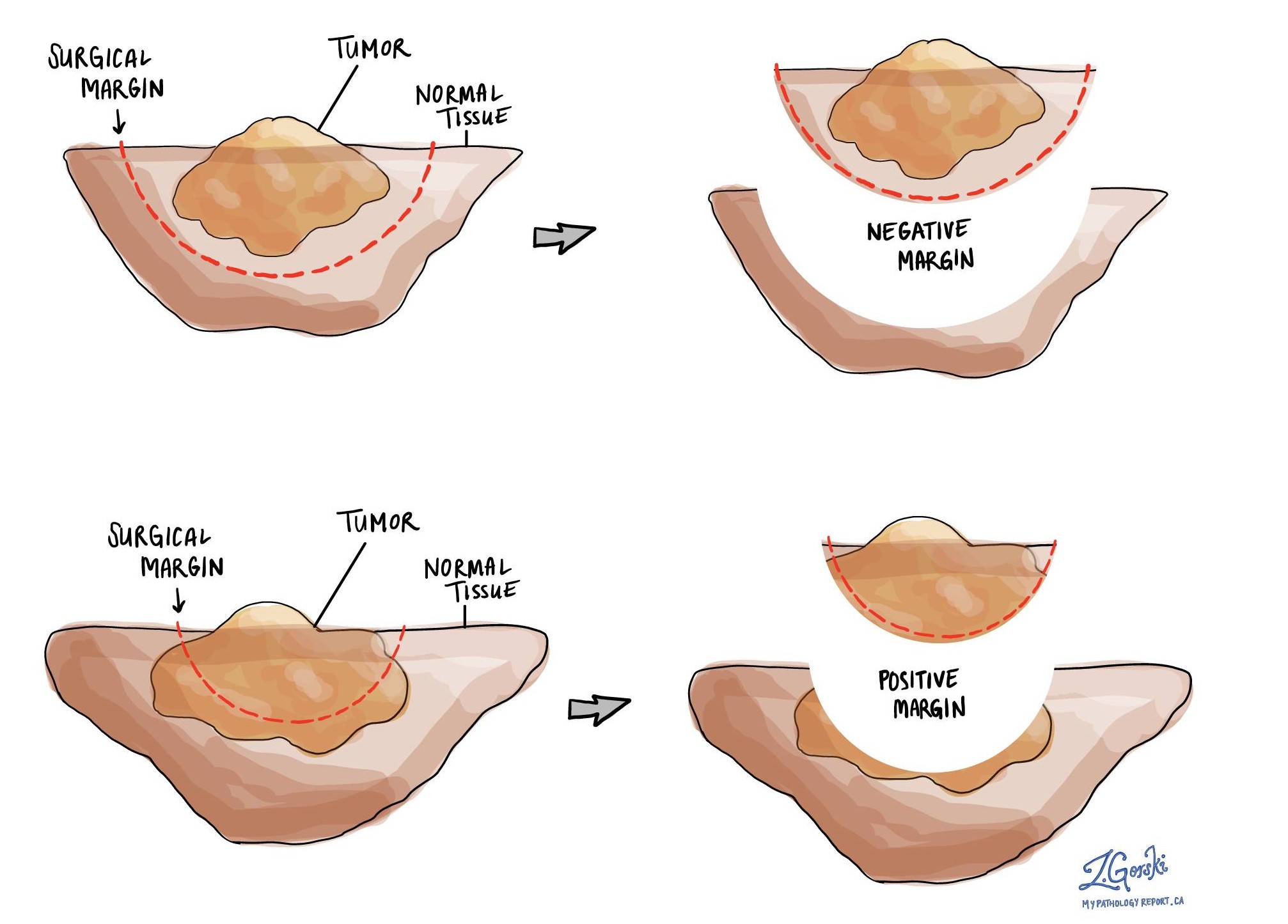

What is a margin?

In pathology, a margin is the edge of a tissue that is cut when removing a tumour from the body. The margins described in a pathology report are very important because they tell you if the entire tumour was removed or if some of the tumour was left behind. The margin status will determine what (if any) additional treatment you may require.

Most pathology reports only describe margins after a surgical procedure called an excision or resection has been performed for the purpose of removing the entire tumour. For this reason, margins are not usually described after a procedure called a biopsy is performed for the purpose of removing only part of the tumour. The number of margins described in a pathology report depends on the types of tissues removed and the location of the tumour. The size of the margin (the amount of normal tissue between the tumour and the cut edge) depends on the type of tumour being removed and the location of the tumour.

Pathologists carefully examine the margins to look for tumour cells at the cut edge of the tissue. If tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, the margin will be described as positive. If no tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, a margin will be described as negative. Even if all of the margins are negative, some pathology reports will also provide a measurement of the closest tumour cells to the cut edge of the tissue.

A positive (or very close) margin is important because it means that tumour cells may have been left behind in your body when the tumour was surgically removed. For this reason, patients who have a positive margin may be offered another surgery to remove the rest of the tumour or radiation therapy to the area of the body with the positive margin. The decision to offer additional treatment and the type of treatment options offered will depend on a variety of factors including the type of tumour removed and the area of the body involved. For example, additional treatment may not be necessary for a benign (non-cancerous) type of tumour but may be strongly advised for a malignant (cancerous) type of tumour.