by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Bibianna Purgina MD FRCPC

February 29, 2024

A central atypical cartilaginous tumour (ACT) is a type of bone cancer. The tumour is called “cartilaginous” because it is made up of cartilage-producing cells. Cartilage is a type of connective tissue normally found throughout the body. These tumours start on the inside of a bone in a space called the “medulla”. Another name for this tumour is low-grade central chondrosarcoma.

What are the symptoms of a central atypical cartilaginous tumour?

Symptoms of a central atypical cartilaginous tumour include pain and swelling over the involved bone. However, many patients with this tumour will experience no symptoms and the tumour will be found incidentally when imaging is performed for another reason.

What causes a central atypical cartilaginous tumour?

People with the genetic syndrome enchondromatosis who have a mutation in the gene IDH1 or IDH2 are at increased risk for developing central atypical cartilaginous tumours. For people, without enchondromatosis who develop this type of tumour, the cause remains unknown.

What is the difference between a central atypical cartilaginous tumour and a grade 1 chondrosarcoma?

Central atypical cartilaginous tumour and grade 1 chondrosarcoma are very similar tumours. The main difference between these tumours is that central atypical cartilaginous tumours are found in the appendicular skeleton which includes the bones of the arms, legs, hands, and feet. In contrast, grade 1 central chondrosarcomas are found in the axial skeleton which includes the bones of the pelvis, scapula, and skull.

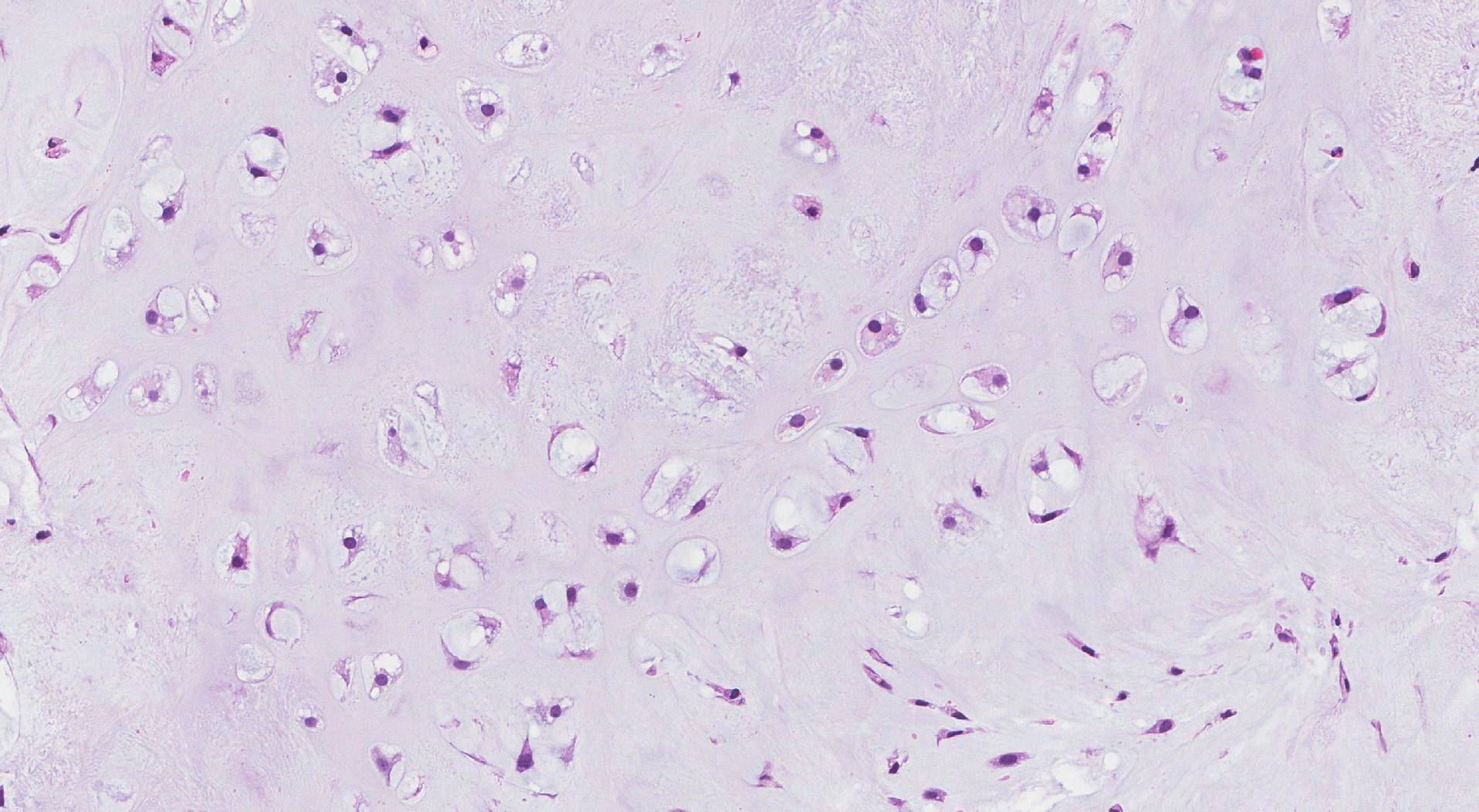

Microscopic features of this tumour

When examined under the microscope, a central atypical cartilaginous tumour is made up of cells producing a type of connective tissue called cartilage. The tumour cells often grow in round groups called lobules. Central atypical cartilaginous tumours can look very similar to a type of non-cancerous tumour called an enchondroma (another tumour made up of cartilage-producing cells), however, unlike enchondroma, the tumour cells in central ACT can be seen growing into and surrounding bone.

Tumour extension

Larger central atypical cartilaginous tumours can break through the bone and grow into surrounding organs or tissue such as muscle, tendons, or joint space. If this has occurred, it may be included in your report and is usually described as extraosseous extension. If the tumour has grown into another part of the bone, that will also be described in your report. Tumour extension is important because it is used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

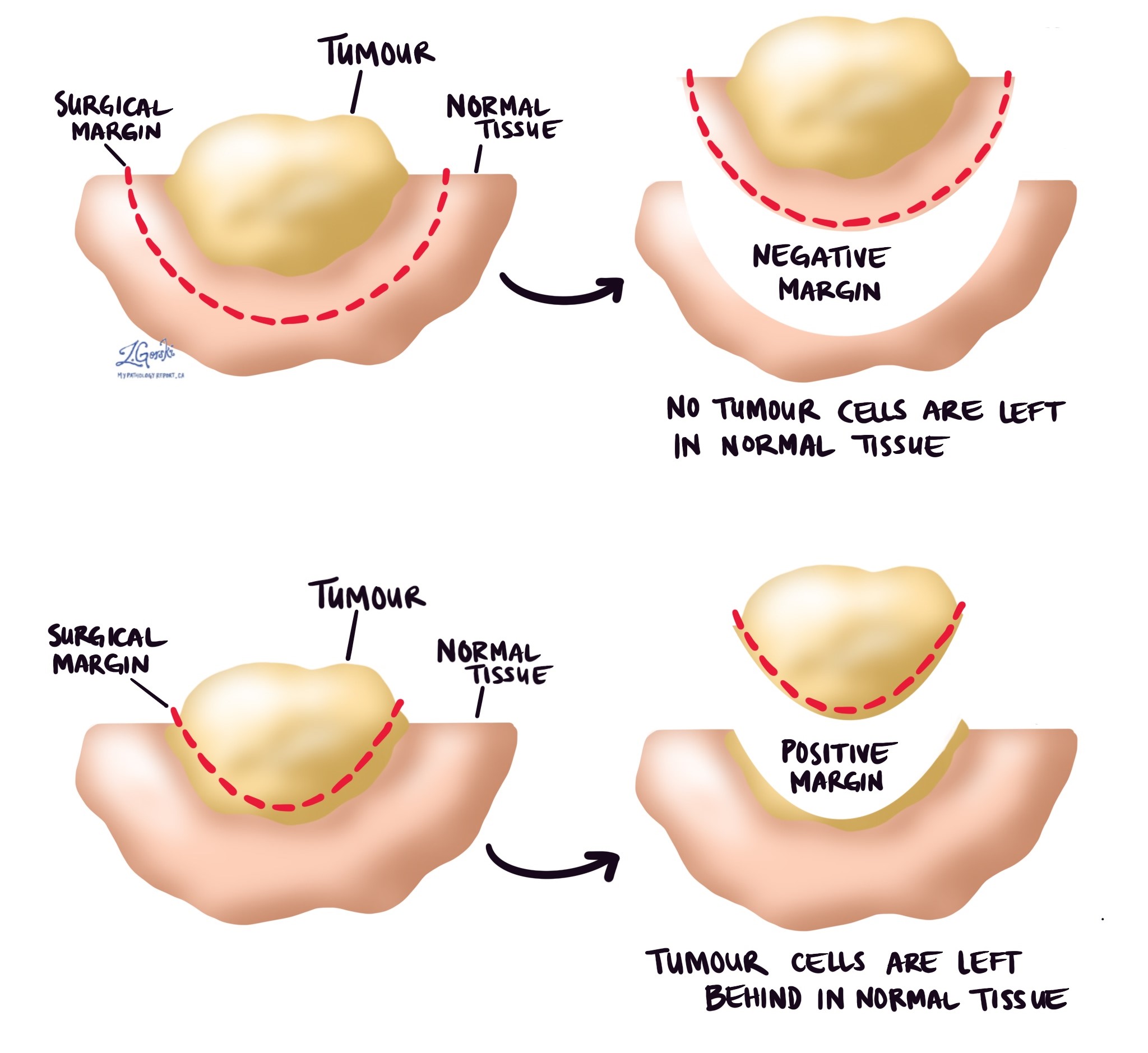

Margins

A margin is any tissue that was cut by the surgeon to remove the bone (or part of the bone) and tumour from your body. Depending on the type of surgery you have had, the types of margins, which could include proximal (the part of the bone closest to the middle of your body) and distal (the part of the bone farthest from the middle of your body) bone margins, soft tissue margins, blood vessel margins, and nerve margins.

All margins will be very closely examined under the microscope by your pathologist to determine the margin status. A margin is considered negative when there are no cancer cells at the edge of the cut tissue. A margin is considered positive when there are cancer cells at the edge of the cut tissue. A positive margin is associated with a higher risk that the tumour will regrow in the same site after treatment (local recurrence).

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

The pathologic stage for central ACT is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis. The pathologic stage will only be included in your report after the entire tumour has been removed. It will not be included after a biopsy.

Tumour stage (pT)

Central ACT is given a pathologic tumour stage (pT) from T1 to T3 based on the tumour size and the number of tumours found in the bone.

- pT1: Tumor ≤ 8 cm in greatest dimension.

- pT2: Tumor > 8 cm in greatest dimension.

- pT3: Discontinuous tumors in the primary bone site.

Nodal stage (pN)

Central ACT is given a pathologic nodal stage (pN) of N0 or N1 based on the examination of lymph nodes.

- Nx – No lymph nodes were sent to pathology for examination.

- N0 – No cancer cells are found in any of the lymph nodes examined.

- N1 – Cancer cells were found in at least one lymph node.

About this article

This article was written by doctors to help you read and understand your pathology report for ACT. The sections above describe the results found in most pathology reports, however, all reports are different and results may vary. Importantly, some of this information will only be described in your report after the entire tumour has been surgically removed and examined by a pathologist. Contact us if you have any questions about this article or your pathology report. Read this article for a more general introduction to the parts of a typical pathology report.