by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

December 12, 2024

This article is designed to help you understand your pathology report for chronic active gastritis of the stomach. Each section explains an important aspect of the diagnosis and what it means for you.

What is chronic active gastritis?

Chronic active gastritis is a condition in which inflammation damages the tissue covering the inside of the stomach, preventing it from functioning normally. The term “chronic” means that the inflammation has been present for a long time. The term “active” means that immune cells called neutrophils are causing ongoing damage to the stomach.

What are the symptoms of chronic active gastritis?

The most common symptoms of chronic active gastritis are abdominal pain (aching or burning) that is worse when the stomach is empty, nausea, bloating, and loss of appetite.

What causes chronic active gastritis?

The most common cause of chronic active gastritis is a stomach infection with Helicobacter pylori bacteria, which pathologists often describe as Helicobacter gastritis. Infection is more common in rural areas and developing parts of the world. Chronic active gastritis can also be seen in people previously treated for Helicobacter pylori. It may persist for months or even years after successful treatment.

Other causes of chronic active gastritis include:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Aspirin and Advil.

- Excessive alcohol intake.

- Bile reflux.

- Autoimmune diseases.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of chronic active gastritis is usually made after a small sample of tissue is removed in a procedure called a biopsy. The tissue is then examined under a microscope by a pathologist. Your pathologist may order additional tests such as immunohistochemistry or special stains to look for Helicobacter pylori micro-organisms in the tissue sample.

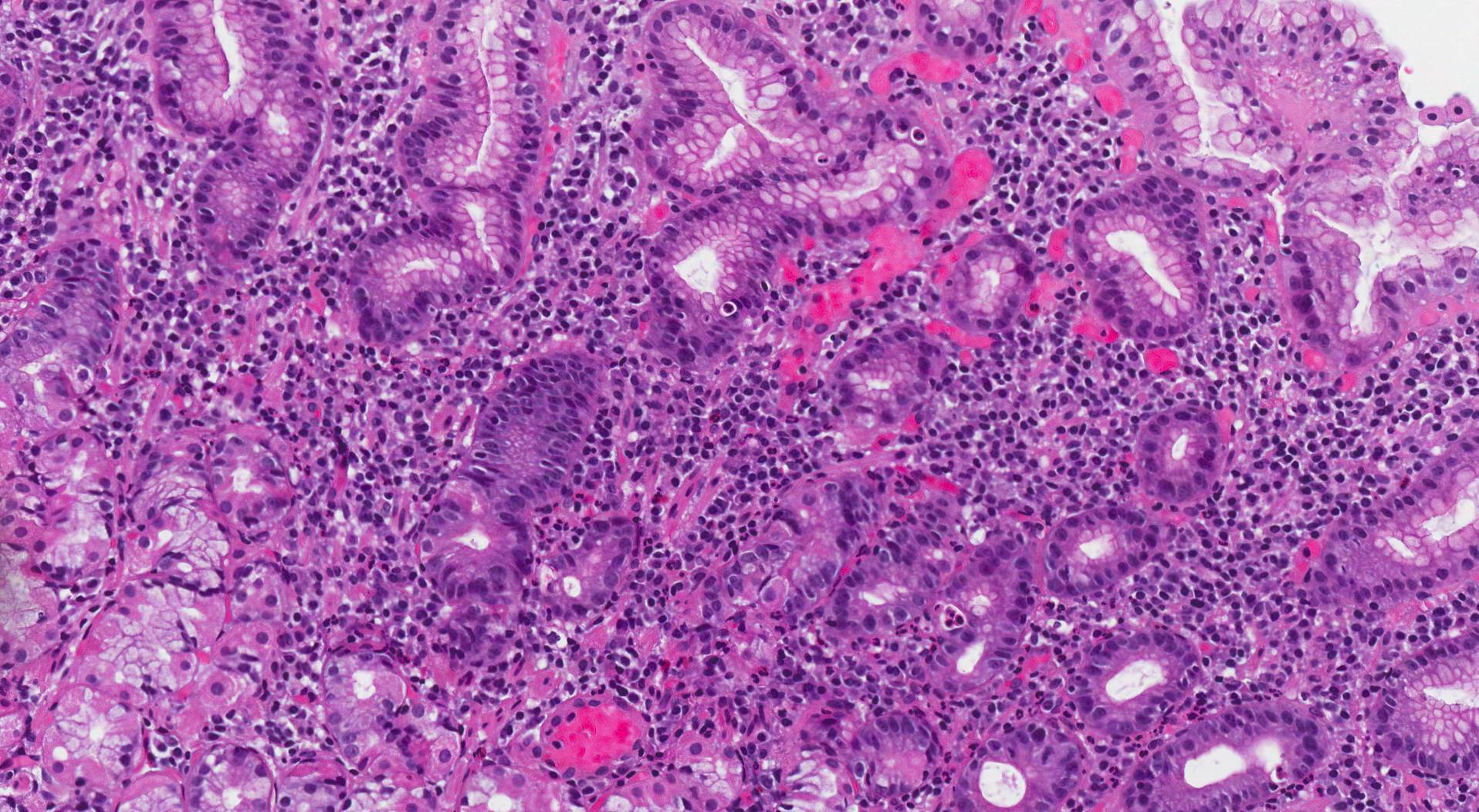

Microscopic features

When examined under the microscope, pathologists look for two features to diagnose chronic active gastritis. The first is chronic inflammation, which means seeing specialized immune cells, such as plasma cells and lymphocytes, in a thin layer of connective tissue called the lamina propria. The second is active or acute inflammation, which means seeing specialized immune cells called neutrophils in the lamina propria or the epithelium. In contrast, inactive gastritis means no neutrophils were seen in the mucosa.

What does it mean if chronic active gastritis is described as mildly, moderately, or severely active?

Some pathologists further divide active gastritis into mildly, moderately, or severely active based on the type of damage caused by the neutrophils.

- Mildly active: Neutrophils are seen in the lamina propria, and some may be seen between epithelial cells. Pathologists sometimes use the term cryptitis to describe this type of activity.

- Moderately active: As with mild activity, neutrophils are seen in the lamina propria. In addition, groups of neutrophils are usually seen inside the glands. Pathologists use the term crypt abscess to describe this type of activity.

- Severely active: At this level of activity, the epithelium that normally covers the inside surface of the stomach is lost. Pathologists use the term ulcer or ulceration to describe this change. An ulcer in the stomach means that the tissue normally found under the epithelium is exposed to the inside environment of the stomach. If not treated, an ulcer can lead to bleeding in the stomach.

Intestinal metaplasia

Chronic active gastritis damages the epithelium that covers the inside of the stomach. If the damage continues for many years, the epithelium is replaced by cells typically found in a part of the gastrointestinal tract called the small intestine. This process is called intestinal metaplasia. If intestinal metaplasia is in the tissue sample, it will be described in your report.

Intestinal metaplasia is important because it increases the risk of developing a type of stomach cancer called adenocarcinoma over time. The risk is higher when another type of change called dysplasia is also seen (see below).

Dysplasia

Dysplasia is a term used to describe abnormal changes in the cells lining the stomach. These changes can occur in the setting of chronic active gastritis. Dysplasia is considered a precancerous condition, meaning that it can sometimes develop into stomach cancer if left untreated.

Chronic active gastritis creates an environment that increases the risk of dysplasia. In particular, chronic inflammation can damage the DNA in the cells lining the inside surface of the stomach and cause them to grow abnormally. Dysplasia often develops in areas of the stomach where the normal lining has been replaced by intestinal-type cells, a condition called intestinal metaplasia.

Dysplasia is important because it can indicate an increased risk of developing stomach cancer. Detecting dysplasia early allows doctors to monitor the condition closely and, in some cases, treat it before it progresses to cancer. Pathologists classify dysplasia into two grades based on how abnormal the cells appear under the microscope.

Low grade dysplasia

In low grade dysplasia, the cells look mildly abnormal, but they still resemble normal stomach cells to some extent. The risk of progression to cancer is lower in chronic active gastritis with grade dysplasia, but careful monitoring with regular follow-up is important to ensure the changes do not worsen over time.

High grade dysplasia

In high grade dysplasia, the cells look much more abnormal, with significant changes in their size, shape, and organization. Chronic active gastritis with high grade dysplasia is more likely to progress to cancer if left untreated. Doctors often recommend removing or treating areas of high grade dysplasia to prevent cancer from developing.

What is the treatment for chronic active gastritis?

Chronic active gastritis caused by Helicobacter pylori infection should be treated with antibiotics. If left untreated, Helicobacter infection can cause stomach ulcers. Untreated Helicobacter infection also increases the risk of developing cancer in the stomach. Patients should also talk to their doctor about any medications they may be taking which can cause chronic active gastritis.