by Bibianna Purgina, MD FRCPC

April 4, 2024

Background:

Dedifferentiated liposarcoma is an aggressive type of cancer that typically starts in a deep location of the body, such as the abdomen. It is called dedifferentiated because it arises from within a similar but less aggressive type of cancer called well differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumour. The term ‘liposarcoma’ means that the cancer was originally made up of fat, but during the process of dedifferentiation, most of the fat cells were replaced by non-fat-containing cancer cells.

What causes dedifferentiated liposarcoma?

Almost all dedifferentiated liposarcomas harbour a genetic alteration involving the genes MDM2 and CDK4. At present, doctors do not know what causes this genetic alteration to occur.

What are the symptoms of dedifferentiated liposarcoma?

Most dedifferentiated liposarcomas present as a large, painless mass. Those located in a deep site, such as the abdomen, may go undetected until the tumour is very large.

How is this diagnosis made?

The first diagnosis of dedifferentiated liposarcoma is usually made after a small tumour sample is removed in a procedure called a biopsy. The biopsy tissue is then sent to a pathologist, who examines it under a microscope. The diagnosis can also be made after the entire tumour is removed as an excision or resection specimen.

Microscopic features of this tumour

Under microscopic examination, dedifferentiated liposarcoma reveals two distinct components. The first comprises fat-producing tumour cells, closely resembling those found in lower-grade, well differentiated liposarcoma. The second component consists of non-fat-producing tumour cells, which often appear highly abnormal and may mimic various other sarcomas, such as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma, and osteosarcoma. The presence of well-differentiated liposarcoma alongside a non-fat-producing sarcoma enables pathologists to diagnose dedifferentiated liposarcoma.

What to look for in your pathology report for dedifferentiated liposarcoma:

French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group (FNCLCC) grade

Pathologists divide dedifferentiated liposarcoma into three grades based on a system created by the French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group (FNCLCC). This system uses three microscopic features to determine the tumour grade: differentiation, mitotic count, and necrosis. These features are explained in more detail below. The grade can only be determined after a tumour sample has been examined under the microscope.

Points (from 0 to 3) are assigned for each of the microscopic features (0 to 3), and the total number of points determines the final grade of the tumour. According to this system, undifferentiated liposarcoma may be either low or high-grade tumours. The tumour grade is important because high-grade tumours (grades 2 and 3) are more aggressive and are associated with a worse prognosis.

Points associated with each grade:

- Grade 1 – 2 or 3 points.

- Grade 2 – 4 or 5 points.

- Grade 3 – 6 to 8 points.

Microscopic features used to determine the grade:

- Tumour differentiation – Tumour differentiation describes how closely the tumour cells look like normal fat cells. Tumours that look very similar to normal fat cells are given 1 point, while those that look very different from normal fat cells are given 2 or 3 points. All dedifferentiated liposarcomas are given 3 points for tumour differentiation.

- Mitotic count – A cell that is in the process of dividing to create two new cells is called a mitotic figure. Tumours that are growing fast tend to have more mitotic figures than tumours that are growing slowly. Your pathologist will determine the mitotic count by counting the number of mitotic figures in ten areas of the tumour while looking through the microscope. Tumours with no mitotic figures or very few mitotic figures are given 1 point, while those with 10 to 20 mitotic figures are given 2 points, and those with more than 20 mitotic figures are given 3 points.

- Necrosis – Necrosis is a type of cell death. Tumours that are growing fast tend to have more necrosis than tumours that are growing slowly. If your pathologist sees no necrosis, the tumour will be given 0 points. The tumour will be given 1 point if necrosis is seen but makes up less than 50% of the tumour or 2 points if necrosis makes up more than 50% of the tumour.

MDM2

MDM2 is a gene that promotes cell division (creating new cells). Normal cells and those in non-cancerous tumours have two copies of the MDM2 gene. In contrast, both well differentiated liposarcoma and dedifferentiated liposarcoma have more than two copies of the MDM2 gene. A test called fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is commonly used to count the number of MDM2 genes in a cell. An increased number of genes (more than two) is called amplification and supports the diagnosis of dedifferentiated liposarcoma.

Tumour size

Tumour size is important because tumours less than 5 cm are less likely to spread to other body parts and are associated with a better prognosis. Tumour size is also used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

Tumour extension

Dedifferentiated liposarcoma starts in fat, but the tumour can grow into or around other tissues and organs. This is called tumour extension. Your pathologist will carefully examine any surrounding tissues or organs submitted for tumour cells, and the result of this examination will be described in your report.

Treatment effect

If you received treatment (either chemotherapy or radiation therapy or both) for your cancer before the tumour is removed, your pathologist will carefully examine the area of the tissue where the tumour was previously identified to see if any cancer cells are still alive (viable). The most commonly used system describes the treatment effect on a scale of 0 to 3 with 0 being no viable cancer cells (all the cancer cells are dead) and 3 being extensive residual cancer with no apparent regression of the tumour (all or most of the cancer cells are alive).

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels, thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, contrast with lymphatic vessels, which carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic vessels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes, scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it enables cancer cells to spread to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the liver, via the blood or lymphatic vessels.

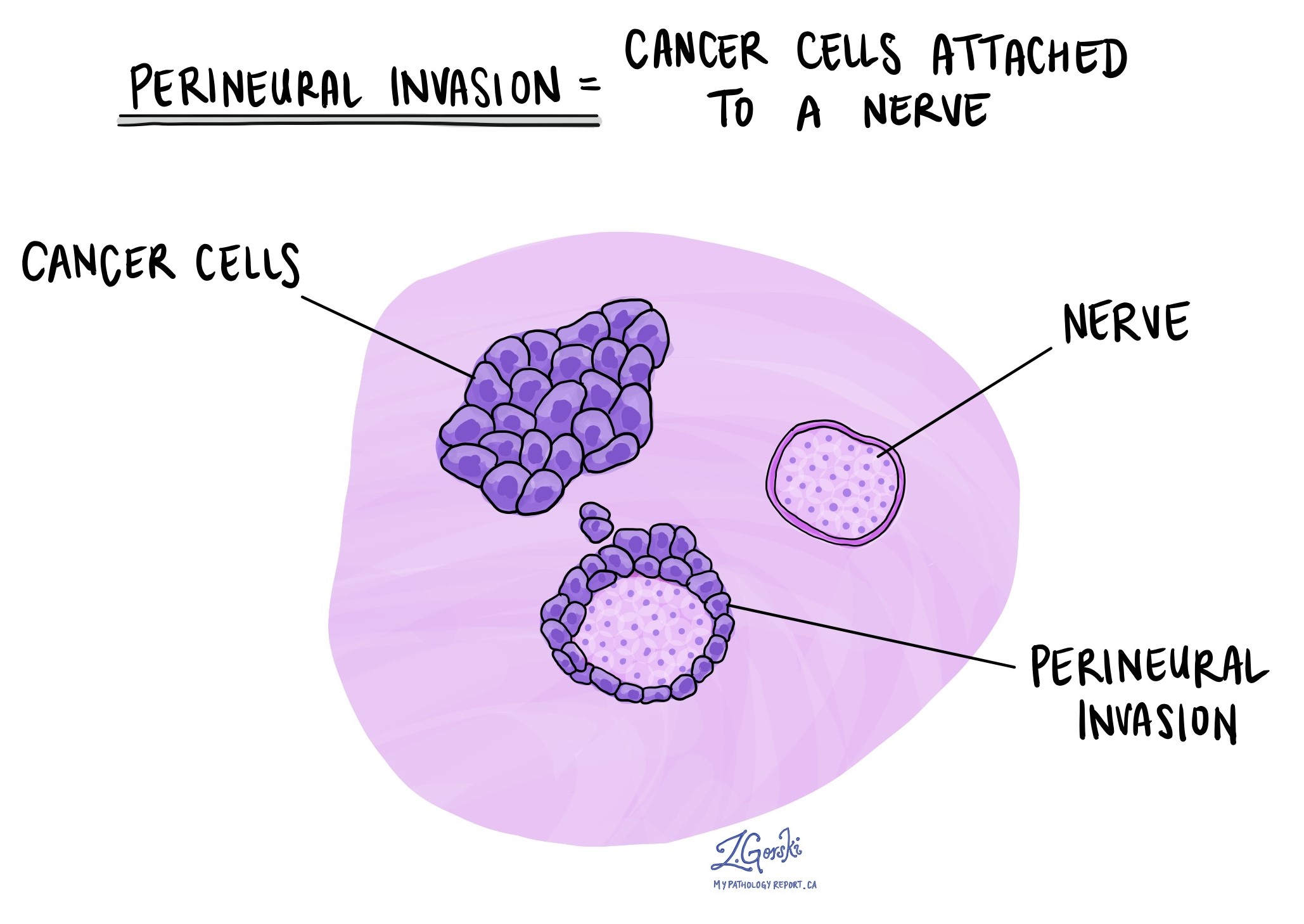

Perineural invasion

Pathologists use the term “perineural invasion” to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that specifically refers to cancer cells found inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. The presence of perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure, like an excision or resection, that removes the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are present at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was fully removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

The pathologic stage for dedifferentiated liposarcoma is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT)

The tumour stage for dedifferentiated liposarcoma varies based on the body part involved. For example, a 5-centimetre tumour that starts in the head will be given a different tumour stage than a tumour that starts deep in the back of the abdomen (the retroperitoneum). However, in most body sites, the tumour stage includes the tumour size and whether the tumour has grown into surrounding body parts.

Tumours starting in the head and neck:

T1 – The tumour is no greater than 2 centimetres in size.

T2 – The tumour is between 2 and 4 centimetres in size.

T3 – The tumour is greater than 4 centimetres in size.

T4 – The tumour has grown into surrounding tissues such as the bones of the face or skull, the eye, the larger blood vessels in the neck, or the brain.

Tumours starting on the outside of the chest, back, or stomach and the arms or legs (trunk and extremities):

T1 – The tumour is no greater than 5 centimetres in size.

T2 – The tumour is between 5 and 10 centimetres in size.

T3 – The tumour is between 10 and 15 centimetres in size.

T4 – The tumour is greater than 15 centimetres in size.

Tumours starting in the abdomen and organs inside the chest (thoracic visceral organs):

T1 – The tumour is only seen in one organ.

T2 – The tumour has grown into the connective tissue surrounding the organ from which it started.

T3 – The tumour has grown into at least one other organ.

T4 – Multiple tumours are found.

Tumours starting in the space at the very back of the abdominal cavity (retroperitoneum):

T1 – The tumour is no greater than 5 centimetres in size.

T2 – The tumour is between 5 and 10 centimetres in size.

T3 – The tumour is between 10 and 15 centimetres in size.

T4 – The tumour is greater than 15 centimetres in size.

Tumours starting in the space around the eye (orbit):

T1 – The tumour is no greater than 2 centimetres in size.

T2 – The tumour is greater than 2 centimetres in size but has not grown into the bones surrounding the eye.

T3 – The tumour has grown into the bones surrounding the eye or other bones of the skull.

T4 – The tumour has grown into the eye (the globe) or the surrounding tissues such as the eyelids, sinuses, or brain.

Nodal stage (pN)

Dedifferentiated liposarcoma is given a nodal stage between 0 and 1 based on the presence or absence of cancer cells in one or more lymph nodes. If no cancer cells are seen in any lymph nodes, the nodal stage is N0. If no lymph nodes are sent for pathological examination, the nodal stage cannot be determined, and the nodal stage is listed as NX. If cancer cells are found in any lymph nodes, then the nodal stage is listed as N1.

About this article

Doctors wrote this article to help you read and understand your pathology report. Contact us if you have questions about this article or your pathology report. For a complete introduction to your pathology report, read this article.