by Bibianna Purgina, MD FRCPC

November 10, 2023

Osteosarcoma is a type of bone cancer and the most common type of sarcoma to develop in a bone. Osteosarcomas more commonly affect teenagers but it can also affect adults. The most common site for osteosarcoma is the long bone of the thigh. Pathologists divide osteosarcomas into histologic types based on how the tumour cells look when examined under the microscope and where the tumour is located on the bone. The most common histologic type is conventional osteoblastic osteosarcoma.

What causes osteosarcoma?

For most patients who develop osteosarcoma, the cause remains unknown. However, some genetic syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome, hereditary retinoblastoma, and Bloom syndrome, increase the risk of developing osteosarcoma.

What are the symptoms of osteosarcoma?

Symptoms of osteosarcoma include a rapidly enlarging and painful mass. As the tumour grows it can cause the bone to fracture (break).

Are there different types of osteosarcoma?

Yes, pathologists divide osteosarcoma into histologic types based on the way the cells look when examined under the microscope and where on the bone the tumour is growing. The histologic type of osteosarcoma is important because it is used to determine the grade.

Histologic types of osteosarcoma include:

- Osteoblastic osteosarcoma.

- Chondroblastic osteosarcoma.

- Fibroblastic osteosarcoma.

- Telangiectatic osteosarcoma.

- Giant cell-rich osteosarcoma.

- Low-grade central osteosarcoma (also called well-differentiated intramedullary osteosarcoma).

- Paget disease-associated osteosarcoma.

- Parosteal osteosarcoma.

- Periosteal osteosarcoma.

- High-grade surface osteosarcoma.

- Epithelioid osteosarcoma.

- Anaplastic osteosarcoma.

- Small cell osteosarcoma.

How is this diagnosis made?

A pathologist typically diagnoses osteosarcoma after examining a small tissue sample that has been removed in a procedure called a biopsy. Under the microscope, osteosarcoma looks like thin or thick strands of immature bone called osteoid mixed with cancer cells. After the diagnosis, most patients are treated first with chemotherapy and then with surgery. During surgery, the tumour is removed completely as a resection. The resection specimen is sent to a pathologist for examination. Your pathologist will examine the tumour under the microscope and give your surgeon and oncologist important information that will help guide your treatment.

What does grade mean and why is the grade important for osteosarcoma?

Pathologists divide osteosarcoma into different three grades – 1, 2, and 3 – based on how similar the tumour cells are to normal bone cells. The cells in a grade 1 tumour look the most like normal bone cells while the cells in a grade 3 tumour look the least like normal bone cells. Instead of numbers, some pathology reports use the terms low, intermediate, and high to describe the grade.

The grade is important because it is used to predict the behaviour of the tumour. For example, grade 1 tumours may come back in the same location (local recurrence) but it is rare for them to spread to more distant parts of the body. Grades 2 and 3 (high-grade) tumours are more likely to spread to distant parts of the body and are usually associated with a worse prognosis.

For most bone tumours, the histologic type of the tumour determines the grade (see the section above for more information). The list below shows the grade associated with each histologic type of osteosarcoma.

Grade 3 (high grade) osteosarcomas:

- Osteoblastic osteosarcoma.

- Chondroblastic osteosarcoma.

- Fibroblastic osteosarcoma.

- Small cell osteosarcoma.

- Telangiectatic osteosarcoma.

- High-grade surface osteosarcoma.

- Paget disease-associated osteosarcoma.

- Extra-skeletal osteosarcoma (a tumour that starts outside of a bone).

- Post-radiation osteosarcoma.

Grade 2 (intermediate grade) osteosarcomas:

- Periosteal osteosarcoma.

Grade 1 (low grade) osteosarcomas:

- Parosteal osteosarcoma.

- Intramedullary well-differentiated osteosarcoma.

What does extraosseous extension mean and why is it important?

Pathologists use the term extraosseous extension to describe a bone tumour that has broken through the outside surface of the bone and has spread into the surrounding tissue such as muscles, tendons, or the space around a joint. Extraosseous extension is important because it is associated with a worse prognosis.

What does it mean if the tumour has spread into another bone?

Some bones are made up of multiple parts. If the tumour has grown from one part of a bone into another, your report will describe the tumour as invading adjacent bones. This is particularly important for tumours in the spine or pelvis because both of these bones are made up of multiple parts. Invasion of adjacent bones is important because it is associated with a worse prognosis. It also increases the pathologic tumour stage.

Has the tumour responded to treatment?

If you received chemotherapy before surgery, your pathologist will examine all the tissue sent to pathology to see how much of the tumour is still viable (alive). This is called the treatment effect. Pathologists often measure the treatment effect as the percentage of the tumour that appears dead when examined under the microscope. For example, if the tumour shows a 65% response to therapy, it means that 65% of the tumour is dead. Typically, osteosarcoma showing 90% or more response to therapy (meaning 90% of the tumour is dead and 10% or less of the tumour is still alive) is associated with a better prognosis.

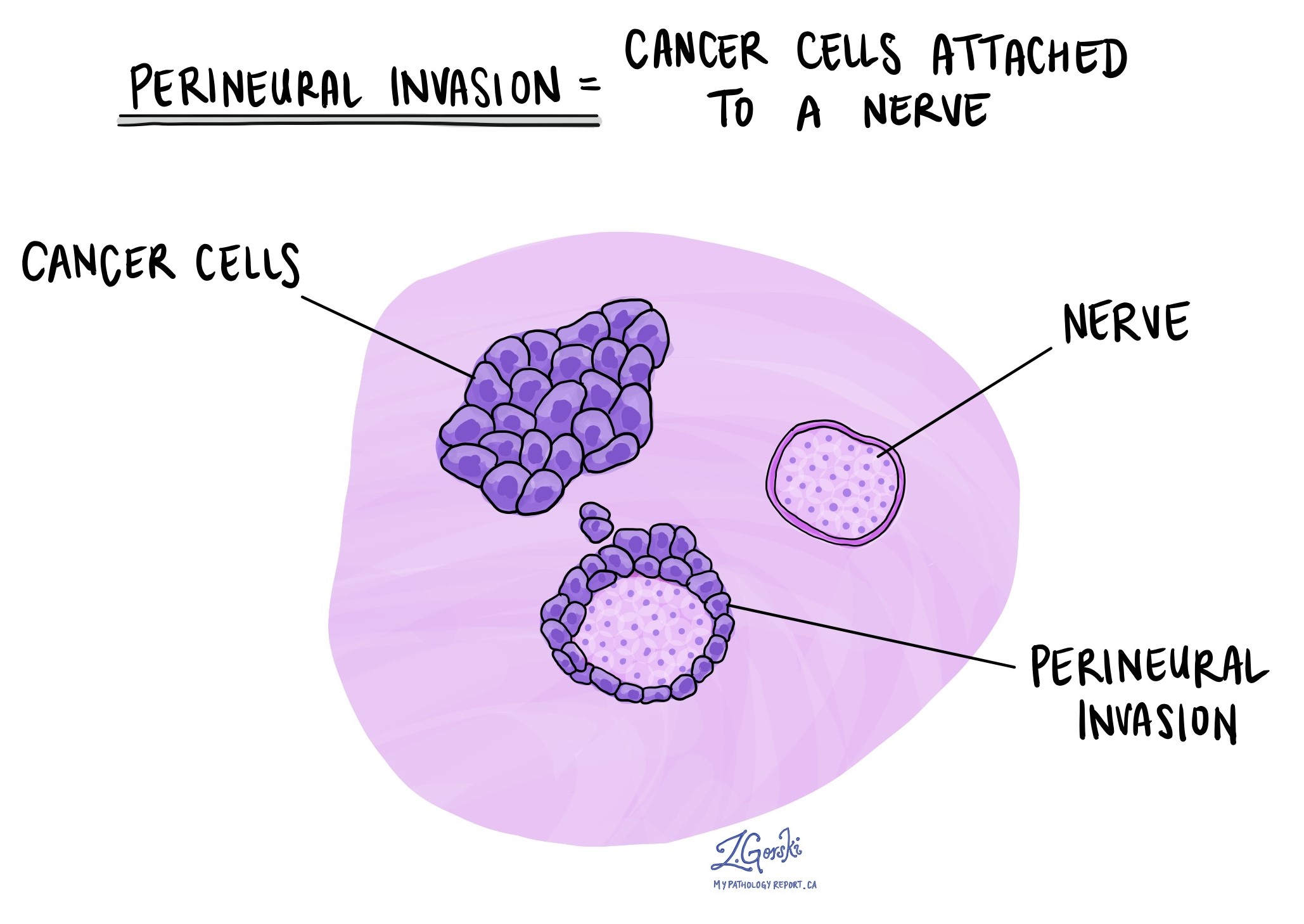

What does perineural invasion mean and why is it important?

Perineural invasion is a term pathologists use to describe cancer cells attached to or inside a nerve. A similar term, intraneural invasion, is used to describe cancer cells inside a nerve. Nerves are like long wires made up of groups of cells called neurons. Nerves are found all over the body and they are responsible for sending information (such as temperature, pressure, and pain) between your body and your brain. Perineural invasion is important because the cancer cells can use the nerve to spread into surrounding organs and tissues. This increases the risk that the tumour will regrow after surgery. If perineural invasion is seen, it will be included in your report. However, it is rare for perineural invasion to be found in osteosarcoma.

What does lymphovascular invasion mean and why is it important?

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells were seen inside a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. The lymphatic vessels connect with small immune organs called lymph nodes that are found throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because cancer cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other parts of the body such as lymph nodes or the lungs. If lymphovascular invasion is seen, it will be included in your report. However, it is rare for lymphovascular invasion to be found in osteosarcoma.

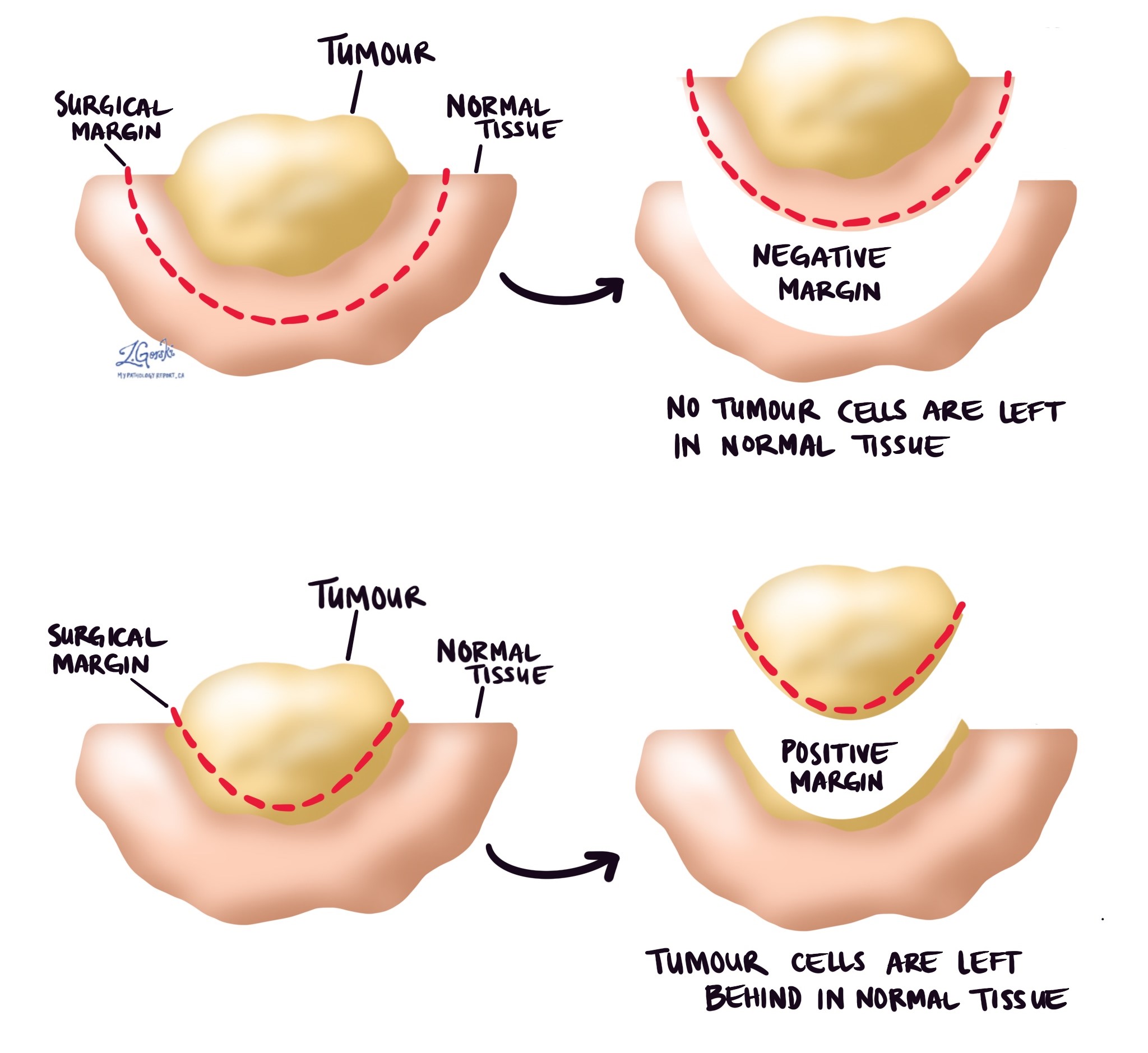

What is a margin and why are margins important?

In pathology, a margin is the edge of a tissue that is cut when removing a tumour from the body. The margins described in a pathology report are very important because they tell you if the entire tumour was removed or if some of the tumour was left behind. The margin status will determine what (if any) additional treatment you may require.

Most pathology reports only describe margins after a surgical procedure called an excision or resection has been performed to remove the entire tumour. For this reason, margins are not usually described after a procedure called a biopsy is performed to remove only part of the tumour. The number of margins described in a pathology report depends on the types of tissues removed and the location of the tumour. The size of the margin (the amount of normal tissue between the tumour and the cut edge) also depends on the type of tumour being removed and the location of the tumour.

Pathologists carefully examine the margins to look for tumour cells at the cut edge of the tissue. If tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, the margin will be described as positive. If no tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, a margin will be described as negative. Even if all of the margins are negative, some pathology reports will also provide a measurement of the closest tumour cells to the cut edge of the tissue.

A positive (or very close) margin is important because it means that tumour cells may have been left behind in your body when the tumour was surgically removed. For this reason, patients who have a positive margin may be offered another surgery to remove the rest of the tumour or radiation therapy to the area of the body with the positive margin. The decision to offer additional treatment and the type of treatment options offered will depend on a variety of factors including the type of tumour removed and the area of the body involved. For example, additional treatment may not be necessary for a benign (non-cancerous) type of tumour but may be strongly advised for a malignant (cancerous) type of tumour.

Common margins for osteosarcoma include:

- Proximal bone margin – This is the part of the bone closest to the middle of your body.

- Distal bone margin – This is the part of the bone farthest from the middle of your body.

- Soft tissue margins – This is the cut edge of any none bone tissue that was removed at the same time as the tumour in the bone.

- Blood vessel margins – This is the cut edge of any large blood vessels removed at the same time as the tumour.

- Nerve margins – This is the cut edge of any large nerve removed at the same time as the tumour.

What are lymph nodes and why are they important?

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour to lymph nodes through small vessels called lymphatics. The cancer cells in osteosarcoma typically do not spread to lymph nodes and for this reason, lymph nodes are not always removed at the same time as the tumour. However, when lymph nodes are removed, they will be examined under a microscope and the results will be described in your report.

Cancer cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour although lymph nodes far away from the tumour can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are only typically removed if they are enlarged and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancer cells in the lymph node. Most reports will include the total number of lymph nodes examined, where in the body the lymph nodes were found, and the number (if any) that contain cancer cells. If cancer cells were seen in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) will also be included.

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy is required.

What does it mean if a lymph node is described as positive?

Pathologists often use the term “positive” to describe a lymph node that contains cancer cells. For example, a lymph node that contains cancer cells may be called “positive for malignancy”.

What does it mean if a lymph node is described as negative?

Pathologists often use the term “negative” to describe a lymph node that does not contain any cancer cells. For example, a lymph node that does not contain cancer cells may be called “negative for malignancy”.

What information is used to determine the pathologic stage?

The pathologic stage for osteosarcoma is based on a system called the TNM staging system. This system is used around the world and was created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will give each category a number after examining your tissue sample under the microscope. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT)

For bone cancers such as osteosarcoma, the primary tumour (pT) stage depends on where the tumour is located in your body.

Tumours in the appendicular skeleton

If the tumour is located in your appendicular skeleton (the bones of your arms, legs, shoulder, trunk, skull, or face), it is given a tumour stage of 1, 2 or 3 based on the size of the tumour and whether the tumour was seen in multiple parts of the bone.

- pT1: Tumour is less than or equal to 8 cm.

- pT2: Tumour is greater than 8 cm.

- pT3: Tumour was seen in multiple parts of the bone (discontinuous tumour nodules).

Tumours in the spine

If the tumour is located in your spine, it is given a tumour stage of 1, 2, 3, or 4 based on how far the tumour has grown.

- pT1: Tumour is only seen in one or two adjacent vertebral bones (bones of the spine and the space between them).

- pT2: Tumour is seen in three adjacent vertebral bones.

- pT3: Tumour is seen in four or more adjacent vertebral bones or any nonadjacent vertebral bones.

- pT4: Tumour invades the spinal canal or great vessels.

Tumours in the pelvis

If the tumour is located in your pelvis, it is given a tumour stage of 1, 2, 3, or 4 based on the size of the tumour and how far it has grown.

- pT1: Tumour is in one pelvic bone with no extraosseous extension (tumour is not growing outside of the bone).

- pT1a: Tumour is less than or equal to 8 cm.

- pT1b: Tumour is greater than 8 cm.

- pT2: Tumour is in one pelvic bone with extraosseous extension (tumour is growing outside the bone) or in two bones with no extraosseous extension (tumour is not growing outside the bone).

- pT2a: Tumour is less than or equal to 8 cm.

- pT2b: Tumour is greater than 8 cm.

- pT3: Tumour is in two pelvic bones with extraosseous extension (tumour is growing outside the bone).

- pT3a: Tumour is less than or equal to 8 cm.

- pT3b: Tumour is greater than 8 cm.

- pT4: Tumour is in three pelvic bones or crossing the sacroiliac joint.

- pT4a: Tumour involves sacroiliac joint and extends into the sacral neuroforamen (space where the nerves pass through).

- pT4b: Tumour surrounds the external iliac vessels or extends into a major pelvic vessel.

Other tumour stages

- pT0: No tumour cells were seen after all of the tissue was examined under the microscope. This means that there is no evidence of a primary tumour.

- pTX (primary tumour cannot be assessed): The pathologist could not determine the tumour size or the distance that it had grown. This may happen if the pathologist receives the tumour as several small pieces.

Nodal stage (pN)

Primary bone cancers are given a nodal stage of 0 or 1 based on whether there are cancer cells in one or more lymph nodes.

- pNX: The pathologist is sent no lymph nodes to examine.

- pN0: No tumour cells are seen in any lymph nodes.

- pN1: Tumour cells are found in one or more lymph nodes.

Metastatic stage (pM)

Primary bone cancers are given a metastatic stage (pM) only if a pathologist has confirmed that tumour cells have travelled to another part of the body. They do so by examining tissue from that part of the body.

There are two metastatic stages in primary bone cancers:

- M1a: Tumour cells have travelled to the lungs.

- M1b: Tumour cells have travelled to other bones or another organ.

Because this tissue is not typically sent to the lab, the metastatic stage cannot be determined and is not included in your report.

About this article

This article was written by doctors to help you read and understand your pathology report for osteosarcoma. The sections above describe the results found in most pathology reports, however, all reports are different and results may vary. Importantly, some of this information will only be described in your report after the entire tumour has been surgically removed and examined by a pathologist. Contact us if you have any questions about this article or your pathology report. Read this article for a more general introduction to the parts of a typical pathology report.