by Bibianna Purgina, MD FRCPC

July 25, 2024

Background:

Fibromatosis is a benign (non-cancerous) tumour made up of a specialized type of connective tissue called fibrous tissue. Pathologists divide fibromatosis into two categories depending on where the tumour develops. Tumours that develop just under the skin are called superficial fibromatosis. Tumours that develop deeper within the body are called deep fibromatosis.

Types of fibromatosis

Superficial fibromatosis

These tumours are described as ‘superficial’ because they develop just under the skin, often in the hands or feet. There are other names for superficial fibromatosis, based on where in the body it develops. When this condition develops in the palm of the hand it is called palmar fibromatosis (Dupuytren’s contracture). In this location, it can form hard bumps on the palm of the hand and puckering of the skin. This can make it difficult to extend your fingers. Dupuytren’s contracture is more common in older patients and can affect both hands. When this condition develops on the bottom of the foot (the sole) is called plantar fibromatosis or Ledderhose’s disease. This condition can also involve the penis and is called penile fibromatosis or Peyronie’s disease. Penile fibromatosis typically affects men over the age of 40.

Deep fibromatosis

These tumours are described as ‘deep’ because most tumours start in the wall of the abdomen or the tissues that cover the internal organs. Other names for deep fibromatosis are desmoid tumour, aggressive fibromatosis, abdominal fibromatosis, extra-abdominal fibromatosis, and intra-abdominal fibromatosis. The name used depends on where in the body the tumour was located.

Deep fibromatosis typically develops in teenagers and young adults and the tumour can sometimes cause pain. Although deep fibromatosis is a non-cancerous tumour, it can grow back in the same area after surgery. This is called a local recurrence. The tumour cells in deep fibromatosis will not, however, spread to other parts of the body, as cancers are known to do. Deep fibromatosis can run in families and is seen in genetic syndromes, including familial Adenomatous Polyposis Syndrome (APC)/Gardner syndrome or familial desmoid syndrome.

Some types of deep fibromatosis are given a special name based on the location in the body where the tumour develops. Types of deep fibromatosis include:

- Abdominal fibromatosis: This type develops in or near the muscles in the wall of the abdomen of women, usually during or after pregnancy and can develop in a Cesarean section scar.

- Extra-abdominal fibromatosis: This type usually develops in or near the muscles of the shoulder, chest, back or thigh and can affect men and women equally.

- Intra-abdominal fibromatosis: This type develops in the fat around the bowel or in the pelvis or the back of the abdomen (an area referred to as retroperitoneum).

What are the symptoms of fibromatosis?

The symptoms of fibromatosis depend on the type and location of the tumour.

Deep fibromatosis

- A palpable mass or lump, often in the abdominal wall, shoulders, arms, or legs.

- Pain or discomfort in the affected area.

- Restricted movement or functional impairment, especially if the tumour is near joints or muscles.

- Swelling or inflammation in the area of the tumour.

Palmar Fibromatosis (Dupuytren’s Contracture)

- Nodules or lumps in the palm of the hand.

- Thickened cords of tissue that can cause the fingers to contract or bend towards the palm.

- Difficulty in straightening or fully extending the fingers.

Plantar fibromatosis (Ledderhose disease)

- Nodules or lumps in the arch of the foot.

- Pain when walking or standing.

- Difficulty in wearing shoes due to discomfort.

Penile fibromatosis (Peyronie’s disease)

- Development of fibrous plaques on the penis.

- Curvature of the penis during erection.

- Pain during erections.

- Erectile dysfunction or difficulty with sexual intercourse.

What causes fibromatosis?

The exact cause of fibromatosis is not well understood, but several factors may contribute to its development:

- Genetic factors: Some forms of fibromatosis, such as deep fibromatosis, are associated with a genetic syndrome called familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Individuals with FAP are at a higher risk of developing deep fibromatosis.

- Hormonal influences: Estrogen is believed to play a role in the growth of some types of fibromatosis, particularly deep fibromatosis. These tumours are more common in women and may grow during pregnancy.

- Trauma or injury: Some cases of fibromatosis develop at the site of previous trauma or injury. This is particularly noted in palmar and plantar fibromatosis.

- Inflammatory and immune responses: Chronic inflammation or abnormal immune responses may contribute to the formation of fibromatosis.

- Idiopathic factors: In many cases, the cause of fibromatosis is unknown (idiopathic).

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of fibromatosis is usually made after a small piece of the tumour is removed in a procedure called a biopsy or after the entire tumour is removed in a procedure called an excision. The tissue is then sent to a pathologist, who examines it under a microscope. Sometimes additional tests such as immunohistochemistry or molecular testing may be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Because deep fibromatosis can look like other tumours that develop from fibrous tissue, it can be difficult for your pathologist to make a definite diagnosis of deep fibromatosis with only the small amount of tissue provided with a biopsy. However, your pathologist may suggest this diagnosis as a possibility to your clinician in the pathology report.

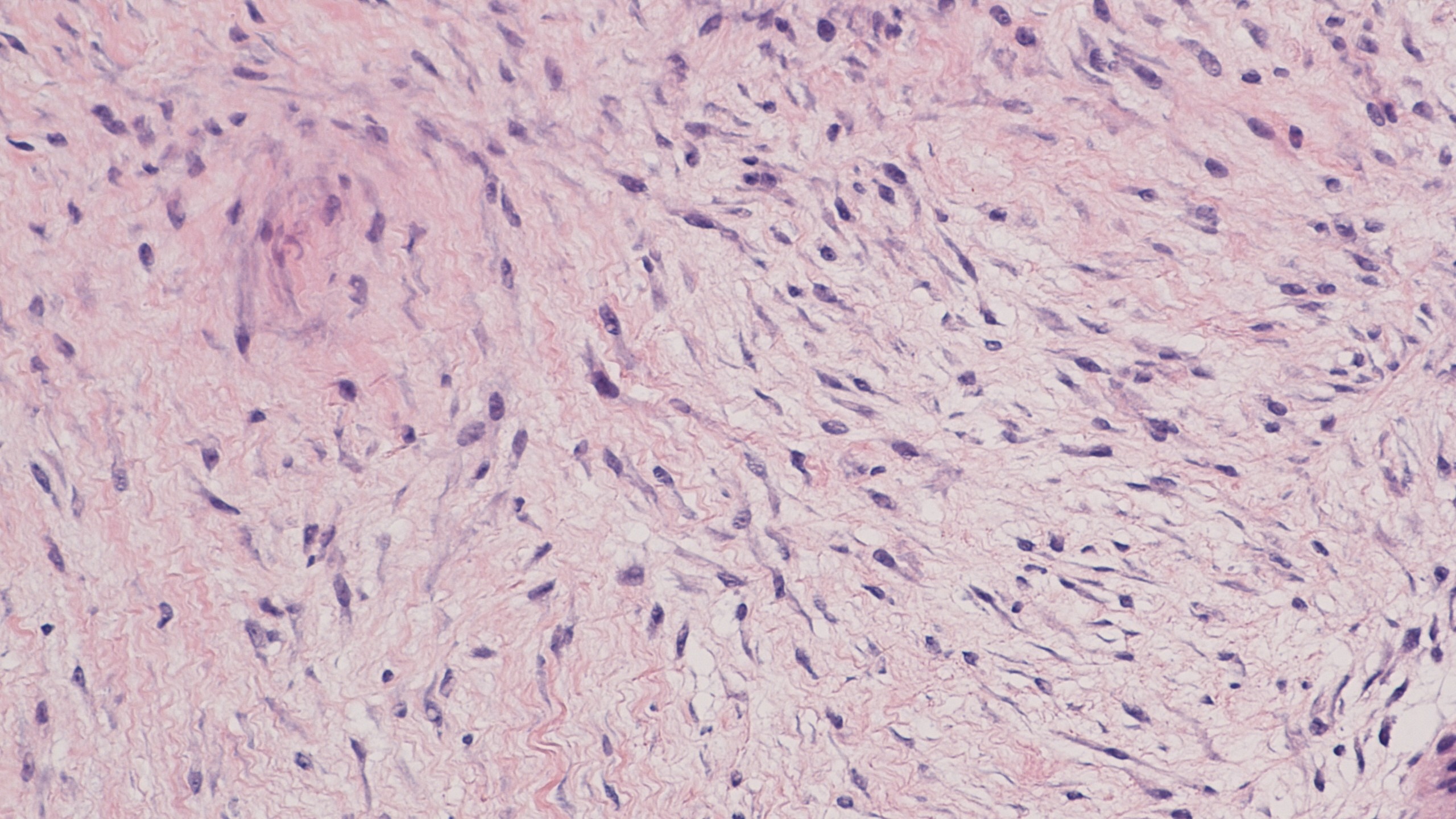

Microscopic features of fibromatosis

When viewed under the microscope, both superficial and deep fibromatosis comprise long thin spindle cells that look like the cells found in normal fibrous tissue. These cells are called fibroblasts and myofibroblasts and they form a mass that grows into the surrounding normal tissues. The number of these fibroblasts and myofibroblasts cells in the tumour changes depending on its age. Long-lived tumours usually have fewer cells.

Immunohistochemistry

Your pathologist may also perform a test called immunohistochemistry to look at the proteins being made by the tumour cells. When this test is performed, the tumour cells in fibromatosis are often described as positive or reactive for the proteins smooth muscle actin and desmin. In addition, the cells in deep fibromatosis often show abnormal expression of a protein called beta-catenin. This protein is normally found in a part of the cell called the membrane. In contrast, in deep fibromatosis, the beta-catenin protein does not move normally to the cell’s membrane. Instead, the beta-catenin protein builds up in a part of the cell called the nucleus. Pathologists often describe this as nuclear expression. If the beta-catenin protein is found mostly in the cell’s nucleus, this is considered abnormal and may be associated with a mutation in the genes for either APC or CTNNB1.

Molecular tests

Some people inherit particular genes that put them at a much higher risk of developing tumours such as fibromatosis. The two most common syndromes associated with fibromatosis are Familial Adenomatosis Polyposis Syndrome/Gardner Syndrome and familial desmoid syndrome.

Pathologists often perform a test called next-generation sequencing (NGS) on a piece of the tumour tissue to look for the changes associated with these syndromes. This type of testing can be done on the biopsy specimen or when the tumour has been surgically removed.

Tumour extension

Deep fibromatosis starts in connective tissue but the tumour cells often grow into surrounding organs such as muscles, bone and blood vessels. This is called tumour extension. Tumour extension is important because tumours that extend very widely into surrounding tissues may be more difficult to remove fully and may grow back after surgery.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure, like an excision or resection, that removes the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are present at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was fully removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

About this article

Doctors wrote this article to help you read and understand your pathology report. If you have additional questions, contact us.