By Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

January 28, 2026

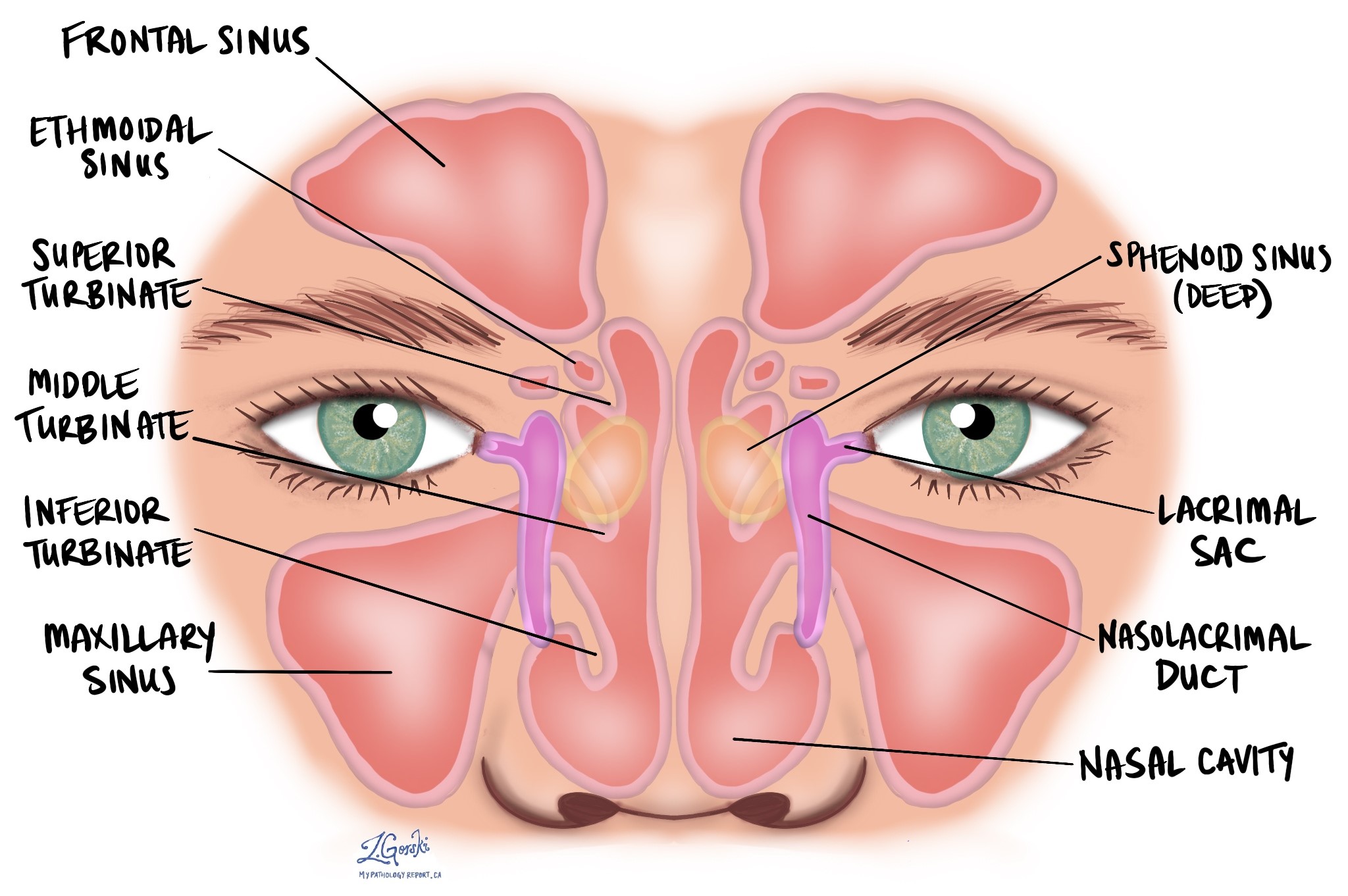

HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma is a type of cancer that starts from squamous cells, which are flat cells lining the inside of the nasal cavity and the paranasal sinuses. The nasal cavity is the hollow space inside the nose that helps warm and filter air, while the paranasal sinuses are air-filled spaces in the bones around the nose that help produce mucus and reduce the weight of the skull.

This cancer is linked to infection with high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV can change how squamous cells grow and divide, allowing them to form a tumour over time. HPV-associated tumours in this area are considered a distinct type of squamous cell carcinoma because they behave differently from tumours not related to HPV.

This article explains how HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma is diagnosed, what pathologists look for in the tissue, and how these findings help guide treatment and prognosis.

What are the symptoms of HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma?

The symptoms of HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma depend on the tumour’s size and exact location. Early tumours may cause mild or vague symptoms, while larger tumours can produce more noticeable problems.

Common symptoms include nasal blockage or congestion, nosebleeds, facial pain or pressure, swelling in or around the nose, difficulty breathing through one nostril, and a reduced sense of smell. Some tumours cause few symptoms at first and are only discovered once they grow larger or extend into nearby structures.

What causes HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma?

HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma is caused by infection with high-risk HPV. The virus interferes with normal cell cycle control, allowing squamous cells to grow uncontrollably.

Other factors, such as smoking or exposure to certain workplace chemicals, may increase overall cancer risk, but HPV plays the central role in this specific tumour type.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses is made by combining imaging studies, tissue sampling (biopsy or surgical resection), and specialized pathologic testing. Each step provides different information, and together they allow doctors to confirm the diagnosis and understand how advanced the tumour is.

Imaging

Imaging studies are an important part of the evaluation. Still, they cannot reliably distinguish HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma from other tumours of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. For this reason, imaging is used mainly to show where the tumour is located and how far it has spread, rather than to make the final diagnosis.

On CT and MRI scans, these tumours usually appear as aggressive soft-tissue masses that can destroy the thin bones of the surrounding sinuses. They most often arise in the maxillary sinus, followed by the ethmoid sinuses and the nasal cavity. Because many tumours are diagnosed at a later stage, imaging may show spread into nearby areas such as the eye socket (orbit), cheek, and deep facial spaces, or the base of the skull.

Doctors often use both CT and MRI together. CT scans are best for showing bone damage, while MRI provides better detail of soft tissues, including spread into muscles, nerves, or the eye. Imaging helps guide biopsy, surgical planning, and tumour staging, but the final diagnosis depends on microscopic examination of tissue.

Biopsy or surgical removal

To make a definitive diagnosis, a biopsy is required. This involves removing a small sample of tissue from the tumour, usually through the nose using an endoscope. In some cases, the diagnosis is made after surgical removal of the tumour, especially if a biopsy was not previously performed or did not provide enough information.

The tissue sample is sent to a pathologist, a doctor who specializes in diagnosing disease by examining tissue.

Microscopic features

Under the microscope, HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma shows a characteristic appearance.

The tumour is usually made up of nests, lobules, or ribbon-like groups of tumour cells. These groups often grow in a smooth, pushing pattern into surrounding tissue rather than breaking through irregularly. Even when the tumour grows deeply or destroys bone, the surrounding tissue often shows little reaction.

In some cases, the tumour grows in a papillary pattern, forming finger-like projections along the surface lining. These projections may spread across nearby normal epithelium.

The tumour cells typically have large nuclei and relatively little cytoplasm, so the nucleus occupies most of the cell. Cells near the edges of tumour nests often line up in an organized way (called peripheral palisading), while cells toward the centre appear flatter.

The degree of abnormality can vary from case to case. Some tumours look only mildly abnormal, while others show more obvious changes. Areas of tumour cell death (necrosis) may be present. Unlike many other cancers, HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma is not graded based on how abnormal the cells look.

Although most cases show the classic non-keratinizing appearance, some tumours may show keratinizing, basaloid, or mixed (adenosquamous) features.

Immunohistochemistry and HPV testing

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a laboratory test that uses antibodies to detect specific proteins in tumour cells. Most HPV-associated tumours show strong, diffuse positivity for p16, a protein that becomes overexpressed when high-risk HPV disrupts normal cell control. A p16-positive result strongly supports HPV involvement.

To confirm HPV infection, in situ hybridization (ISH) may be performed. This test detects high-risk HPV DNA directly within the tumour cells and is highly specific.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) indicates that tumour cells are present within lymphatic channels or blood vessels. These vessels serve as pathways for cancer cells to travel to other parts of the body, including lymph nodes and distant organs.

The presence of lymphovascular invasion increases the risk that the cancer has spread beyond the original tumour site.

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion (PNI) occurs when tumour cells grow along or around a nerve. Nerves act like communication cables, carrying signals such as pain and sensation.

When cancer cells spread along nerves, there is a higher risk of tumour recurrence after surgery because tumour cells may extend beyond the visible mass.

Margins

A margin is the edge of tissue that is cut during surgery to remove a tumour. Margins are assessed only after the entire tumour has been surgically removed, not after a biopsy.

Pathologists examine margins to see whether tumour cells reach the cut edge of the tissue:

-

A negative margin means no tumour cells are seen at the edge, suggesting the tumour was removed entirely.

-

A positive margin means tumour cells are present at the edge, indicating that some cancer may remain in the body.

-

Some reports also describe how close tumour cells are to the margin, even if the margin is negative.

For cancers of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, margin assessment can be challenging. These tumours are often removed in multiple pieces rather than as a single intact specimen, which can make it difficult or impossible to determine whether all margins are clear reliably. In such cases, the pathology report may state that margins cannot be fully assessed or are indeterminate.

Even when margins are difficult to evaluate, the margin information—along with tumour stage and lymph node findings—helps guide decisions about additional treatment such as radiation therapy.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs that filter lymph fluid. Cancer cells can spread from the tumour to nearby lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels.

Lymph nodes removed during surgery are examined under the microscope. If cancer cells are found, the node is described as positive. The report may also describe the size of the tumour deposit and whether tumour cells extend beyond the lymph node (extranodal extension).

Lymph node involvement helps determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN) and guides decisions about additional treatment such as radiation, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy.

Pathologic stage

The pathologic stage describes how much cancer is present in the body and where it is located. For HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, staging is based on the TNM system, which looks at:

-

T (tumour) – the size of the tumour and how far it has grown into nearby structures.

-

N (nodes) – whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes.

-

M (metastasis) – whether the cancer has spread to distant parts of the body.

This information helps doctors choose the best treatment and estimate prognosis. In general, higher stage numbers indicate more advanced disease.

Tumour stage (pT)

The tumour stage depends on where the cancer started, because the anatomy and patterns of spread differ between the maxillary sinus, nasal cavity, and ethmoid sinus.

Maxillary sinus

-

Tis (carcinoma in situ) – Cancer cells are limited to the surface lining and have not invaded deeper tissue.

-

T1 – Tumour is confined to the lining of the maxillary sinus without bone destruction.

-

T2 – Tumour causes bone destruction or extends into nearby areas such as the hard palate or middle nasal passage, but not the back wall of the sinus or deeper spaces.

-

T3 – Tumour invades deeper areas such as the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, tissues behind the sinus, the floor or inner wall of the eye socket (orbit), the ethmoid sinuses, or nearby soft tissues.

-

T4a (moderately advanced) – Tumour extends into structures such as the front of the orbit, cheek skin, cribriform plate, or frontal or sphenoid sinuses.

-

T4b (very advanced) – Tumour invades critical areas such as the brain, cranial nerves, skull base, or major blood vessels.

Nasal cavity and ethmoid sinus

-

Tis (carcinoma in situ) – Cancer cells are confined to the surface lining.

-

T1 – Tumour is limited to one area of the nasal cavity or ethmoid sinus, with or without bone involvement.

-

T2 – Tumour involves two areas in the nasal cavity or ethmoid sinus or extends to nearby areas, with or without bone involvement.

-

T3 – Tumour invades structures such as the floor or inner wall of the orbit, maxillary sinus, palate, or cribriform plate.

-

T4a (moderately advanced) – Tumour invades the front of the orbit, cheek skin, nearby bones, or minimal skull base.

-

T4b (very advanced) – Tumour invades the brain, cranial nerves, or deep skull base structures.

Nodal stage (pN)

The nodal stage describes whether cancer has spread to lymph nodes in the neck.

-

N0 – No cancer is found in nearby lymph nodes.

-

N1 – Cancer is found in a single lymph node on the same side of the neck, 3 cm or smaller, without spread outside the node.

-

N2 – Cancer is found in one or more lymph nodes, none larger than 6 cm. This includes:

-

A single node with spread outside the node, or

-

Multiple nodes on one or both sides of the neck without spreading outside the nodes.

-

-

N3 – More advanced lymph node involvement, including:

-

A lymph node larger than 6 cm, or

-

Any lymph node with tumour spreading beyond the lymph node capsule (extranodal extension).

-

If no lymph nodes are removed for examination, the nodal stage is reported as pNX.

Prognosis

The prognosis for a patient diagnosed with HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma depends on tumour size, location, stage, and lymph node involvement. Overall, the five-year survival rate for sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma is approximately 60%.

Some studies suggest that HPV-associated tumours may have a better prognosis than tumours not linked to HPV, but outcomes still vary from person to person.

Questions to ask your doctor

- Were the surgical margins negative?

-

Did the cancer spread to any lymph nodes?

-

Do I need additional treatment such as radiation, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy?

-

How will this diagnosis affect my long-term follow-up?