by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD

March 27, 2024

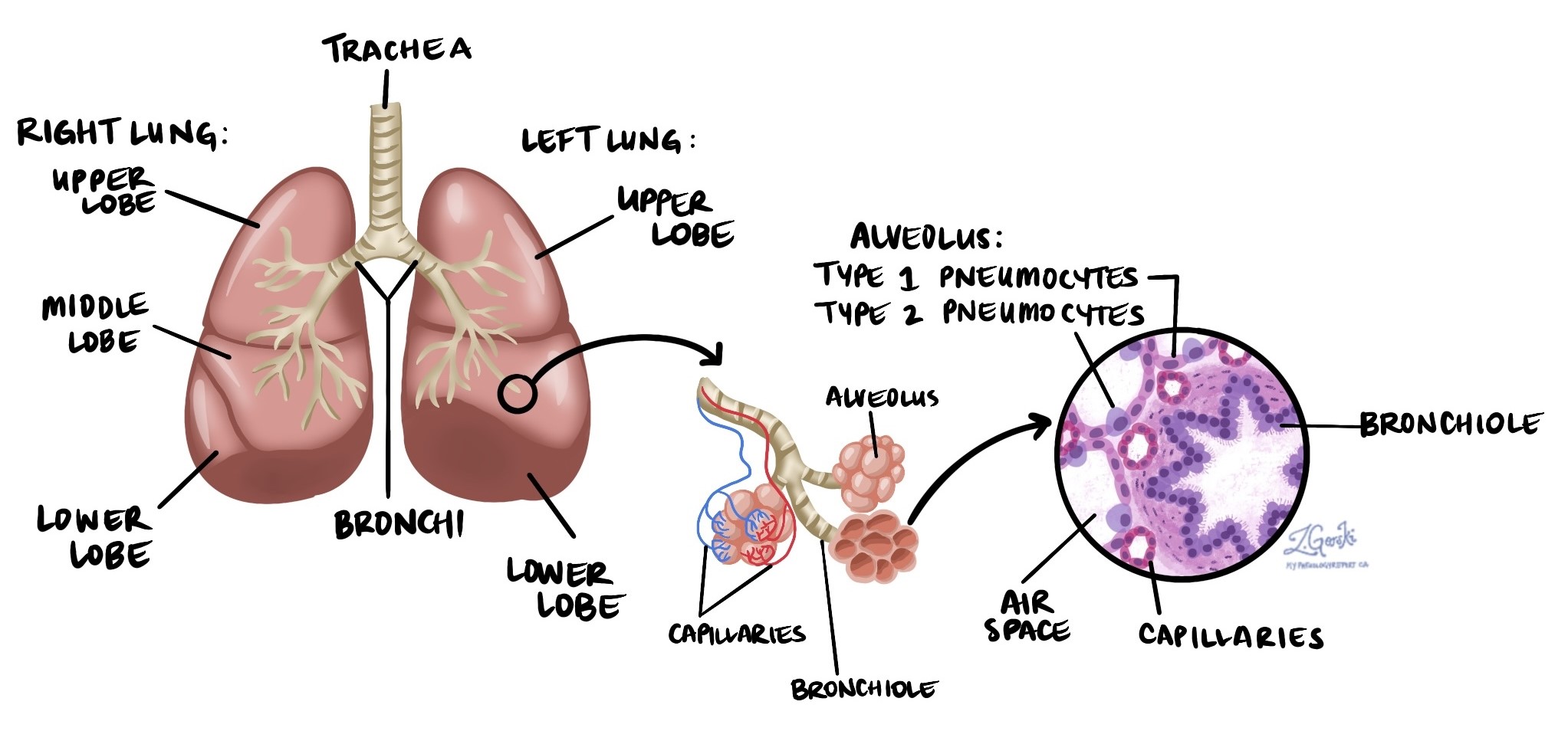

Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of lung cancer. It accounts for about 40% of all lung cancer cases in North America. Adenocarcinoma is a type of non-small cell lung cancer, or NSCLC, which is the most frequently diagnosed category of lung cancers. Adenocarcinoma starts from specialized cells called pneumocytes. These cells are found on the inner lining of tiny air sacs called alveoli. Alveoli are small air spaces in the lungs where oxygen enters the blood and carbon dioxide is removed. Because adenocarcinoma often starts near the edges of the lungs, it may be discovered at an early stage on imaging tests like X-rays or CT scans.

What causes adenocarcinoma in the lung?

The leading cause of adenocarcinoma is tobacco smoking. Other less common causes include radon exposure, occupational agents, and outdoor air pollution.

What are the symptoms of adenocarcinoma in the lung?

Symptoms of lung adenocarcinoma include a persistent or worsening cough, coughing up blood, chest pain, and shortness of breath. Tumours that have spread to other parts of the body may cause additional symptoms depending on the location in the body. For example, tumours that spread to bones may cause bone pain and can cause the bone to break. Doctors describe this as a pathologic fracture.

What conditions are associated with adenocarcinoma of the lung?

In many cases, adenocarcinoma starts from a pre-cancerous disease called atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH). The cells in atypical adenomatous hyperplasia look abnormal, but they are not yet cancer cells. Over time, AAH can turn into a more serious condition called adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS). This condition is considered a non-invasive type of lung cancer because the abnormal cells are only seen on the inner surface of the air space,s and the growth is less than 3 centimetres in size. Adenocarcinoma in situ becomes invasive adenocarcinoma if the cancer cells spread into the stroma below the surface of the air space or if the tumour grows to be larger than 3 centimetres in size.

How is this diagnosis made?

The initial diagnosis of adenocarcinoma in the lung is typically made after a small sample of tissue is removed during a procedure called a biopsy or fine needle aspiration (FNA). Surgery may then be performed to remove the entire tumour. The type of surgery performed to remove the tumour will depend on the size of the tumour and its location in your lung. A wedge resection is usually performed to remove small tumours and those near the outside of the lungs. Lobectomies and pneumonectomies are performed for large tumours or those that are near the centre of the lungs.

Histologic types of adenocarcinoma of the lung

Adenocarcinoma of the lung is classified into histologic types based on its pattern of growth, the way the cancer cells stick together, and the structures it forms. The most common histologic types of adenocarcinoma are lepidic, solid, acinar, papillary, and micropapillary.

A tumour may show just one pattern of growth or multiple patterns of growth in the same tumour. If multiple growth patterns are observed, most pathologists will describe the percentage of the tumour composed of each pattern. The predominant pattern is the histologic type that makes up most of the tumour.

Lepidic pattern

Lepidic-type adenocarcinoma of the lung refers to cancer cells that grow along the inner lining of the air spaces, known as alveoli. The cancer cells replace the normal pneumocytes as they grow. This is the most common histologic type of adenocarcinoma. If the tumour is less than 3 cm in size and shows an entirely lepidic pattern of growth, it is called adenocarcinoma in situ.

Acinar pattern

Acinar-type adenocarcinoma of the lung refers to a type of cancer where the cancer cells form small, round groups of cells with an open space in the middle, known as a lumen. This is the second most common histologic type of adenocarcinoma.

Solid pattern

Solid-type adenocarcinoma of the lung refers to a type of cancer where the cancer cells form large groups with minimal space between them. This type of adenocarcinoma is more aggressive than the lepidic and acinar types and more likely to metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes.

Papillary pattern

Papillary-type adenocarcinoma of the lung refers to a type of cancer where the cancer cells form long, finger-like projections of tissue called papillae, which stick together. The papillary type of adenocarcinoma tends to be more aggressive than lepidic predominant tumours, but is less aggressive than the solid or micropapillary types.

Micropapillary pattern

Micropapillary-type adenocarcinoma of the lung refers to a type of cancer where the cancer cells form small groups that sit within a space. This aggressive type of cancer frequently metastasizes (spreads) to lymph nodes and other parts of the lungs.

Tumour grade

Adenocarcinoma of the lung is divided into three grades (well differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated) based on a combination of the predominant (most common) histologic type (pattern of growth) and the worst (or most aggressive) histologic type. The tumour grade is important because it is a good predictor of how the tumour will respond to treatment. This grading scheme is only applied to non-mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung (tumours not producing large amounts of mucin).

Grading scheme for adenocarcinoma of the lung:

- Well differentiated: A mostly or entirely lepidic-type tumour with less than 20% solid or micropapillary growth.

- Moderately differentiated: A mostly or entirely acinar-type or papillary-type tumour with less than 20% solid or micropapillary growth.

- Poorly differentiated: A tumour with greater than 20% solid or micropapillary growth or with areas made up of complex glands or single cells.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a test that allows pathologists to identify specific types of cells based on the chemicals, typically proteins, that these cells are making. Because different types of cells express different IHC markers, pathologists can use this test to distinguish between different types of cancers.

When IHC is performed, adenocarcinoma of the lung usually shows the following results:

- TTF-1 – Positive in 80% of tumours.

- p40 – Negative.

- CK5 – Negative.

- Chromogranin – Negative.

- Synaptophysin – Negative.

Spread through air spaces

Spread through air spaces (STAS) describes a pattern of invasion observed in lung cancer, where cancer cells are seen spreading into the air spaces in the lung tissue outside the tumour. The presence of STAS has been associated with a higher risk of recurrence and worse overall survival in patients with adenocarcinoma of the lungs, especially in those with early-stage disease. Recognizing STAS can therefore provide valuable prognostic information and help in risk stratification.

Pathologists identify STAS by carefully examining the lung tissue surrounding the tumour under a microscope. They look for tumour cells or clusters of cells within the air spaces that are separate from the primary tumour and not attached to the tumour edge, often located at a distance from the tumour mass itself. These cells can be free-floating or attached to the alveolar walls, but are distinguishable from the primary tumour and not explained by other processes such as artefact or lymphovascular invasion.

Multiple tumours

It is not uncommon for more than one tumour to be found in the same lung. When this happens, each tumour will be described separately in your report.

There are two possible explanations for finding more than one tumour:

- The tumour cells from one tumour have spread to another part of the lung. This explanation is more likely when all of the tumours are of the same histologic type. For example, if all of the tumours are acinar-type adenocarcinoma. If the tumours are on the same side of the body, the smaller tumours are called nodules. If the tumours are on different sides of the body (right and left lung), the smaller tumour is called metastasis.

- The tumours have developed separately. This is the more likely explanation when the tumours are of different histologic types. For example, one tumour is an adenocarcinoma while the other is a squamous cell carcinoma. In this situation, the tumours are considered separate primaries and not metastatic disease.

Pleural invasion

The pleura is a thin layer of tissue that covers the lungs and lines the inner surface of the chest cavity.

It has two layers:

-

Visceral pleura: The layer attached directly to your lungs.

-

Parietal pleura: The layer lining the chest wall and diaphragm.

When tumour cells grow beyond the lung and invade the pleura, it is called pleural invasion. Pleural invasion is important because it affects both staging and prognosis:

-

Tumour stage: Tumours invading the pleura are considered more advanced. Pleural invasion increases the tumour’s T-stage in the TNM staging system.

-

Prognosis: Patients with pleural invasion generally have a worse prognosis because the cancer is more aggressive and likely to spread.

Lymphovascular invasion

Cancer cells can spread into tiny blood vessels or lymphatic channels, a process called lymphovascular invasion. Blood vessels carry blood throughout the body, while lymphatic channels carry lymph fluid, which plays a crucial role in immune function. When tumour cells enter these channels, they can spread to other parts of the body, such as lymph nodes, the liver, or bones. Finding lymphovascular invasion means a higher risk of cancer spreading.

Margins

In pathology, a margin refers to the edge of tissue removed during surgery to remove a tumour. After lung surgery, pathologists carefully examine all of these tissue edges under a microscope to determine if the tumour has been completely removed.

Margins assessed in lung cancer surgeries typically include:

-

Bronchial margin – This is where the surgeon cuts through the airway.

-

Vascular margin – These are the areas where large blood vessels near the tumour are cut.

-

Parenchymal margin – This margin includes the edge of lung tissue around the tumour.

-

Pleural margin – The pleura is a thin lining surrounding the lung, and this margin is examined to determine if the tumour grows close to or through this lining.

Margins can be described in two ways:

-

Negative margin – No cancer cells are seen at any cut edge. This indicates that the tumour has likely been entirely removed, which is the goal of surgery.

-

Positive margin – Cancer cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue. A positive margin means there could still be tumour cells remaining in your body. Patients with a positive margin may require additional treatments, such as a second surgery or radiation therapy, to remove any remaining tumour cells and reduce the risk of recurrence.

The status of the margins helps your doctor determine the need for additional treatment and plays an important role in predicting the likelihood of the tumour growing back.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped organs that play an essential role in the immune system. They are connected throughout the body by small channels called lymphatic vessels. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour through these lymphatic vessels and into nearby lymph nodes—a process called lymph node metastasis.

Lymph nodes in the lungs and chest are grouped into specific areas, known as lymph node stations. There are 14 different lymph node stations, each with a specific location:

-

Station 1: Lower cervical, supraclavicular, and sternal notch lymph nodes.

-

Station 2: Upper paratracheal lymph nodes.

-

Station 3: Prevascular and retrotracheal lymph nodes.

-

Station 4: Lower paratracheal lymph nodes.

-

Station 5: Subaortic (aortopulmonary window) lymph nodes.

-

Station 6: Para-aortic lymph nodes (near the ascending aorta or phrenic nerve).

-

Station 7: Subcarinal lymph nodes (below the carina, where the trachea splits into bronchi).

-

Station 8: Paraesophageal lymph nodes (alongside the esophagus below the carina).

-

Station 9: Pulmonary ligament lymph nodes.

-

Station 10: Hilar lymph nodes (at the lung hilum, where airways enter the lung).

-

Station 11: Interlobar lymph nodes (between lung lobes).

-

Station 12: Lobar lymph nodes (within lung lobes).

-

Station 13: Segmental lymph nodes (within lung segments).

-

Station 14: Subsegmental lymph nodes (within smaller lung subsegments).

If lymph nodes are removed during surgery, a pathologist carefully examines them under a microscope to see if they contain cancer cells. The pathology report typically includes:

-

The total number of lymph nodes examined.

-

The locations (stations) of the lymph nodes examined.

-

The number of lymph nodes containing cancer cells.

-

The size of the largest group of cancer cells (often called a “focus” or “deposit”).

Lymph node examination provides important information that helps your doctor determine the cancer’s pathologic nodal stage (pN). It also helps predict the likelihood that cancer cells may have spread to other parts of the body, guiding decisions about additional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

Pathologists use the TNM staging system to determine how advanced the cancer is and to help guide treatment decisions.

-

Tumour (T) stage: Based on the size of the tumour and any invasion of surrounding tissues.

-

Node (N) stage: Based on the number of lymph nodes examined and the number that contain cancer cells.

-

Metastasis (M) stage: Based on the spread of cancer cells to distant parts of the body, such as bones or the brain.

Each of these categories is given a number; higher numbers mean more advanced disease.

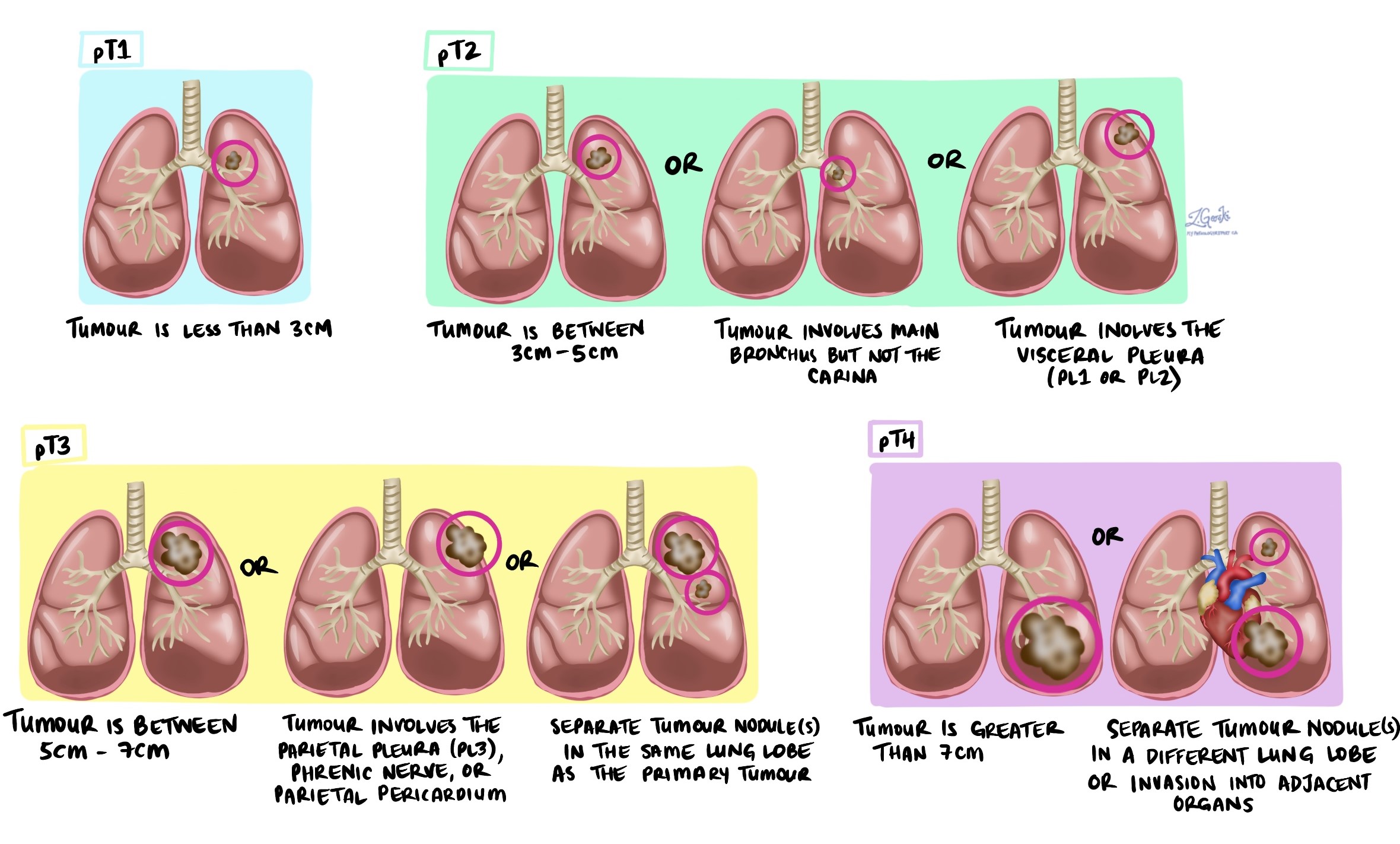

Tumour stage (pT)

-

T1: Tumour is 3 cm or smaller.

-

T2: Tumour is larger than 3 cm but not larger than 5 cm, or it has invaded the visceral pleura or main airways.

-

T3: Tumour is larger than 5 cm but not larger than 7 cm or has grown into nearby tissues.

-

T4: Tumour is larger than 7 cm or has invaded nearby organs such as the heart or esophagus.

Nodal stage (pN)

-

NX: Lymph nodes were not examined.

-

N0: No cancer cells in lymph nodes.

-

N1: Cancer cells in lymph nodes inside the lung or near airways (stations 10–14).

-

N2: Cancer cells in lymph nodes in the central chest near the airways (stations 7–9).

-

N3: Cancer cells in lymph nodes on the opposite side of the chest or in the lower neck (stations 1–6).

Metastatic stage (pM)

-

M0: No distant spread.

-

M1: Cancer has spread to distant parts of the body.

-

MX: Unable to determine if distant spread has occurred.

Biomarkers for adenocarcinoma of the lung

Biomarkers are specific molecules found inside tumour cells. These molecules help doctors understand how the tumour behaves and how it might respond to different treatments. Testing for biomarkers is important in lung cancer because some tumours contain genetic changes or alterations that make them respond well to targeted therapies. Targeted therapies are drugs designed specifically to attack cancer cells with these genetic changes. Identifying these biomarkers helps doctors choose the most effective treatment options.

Pathologists look for biomarkers using specialized laboratory tests. Two common tests include:

-

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) – This test examines many genes at the same time to find mutations (changes in the genetic material of tumour cells). NGS can quickly identify multiple biomarkers from a single tissue sample.

-

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) – This test uses special stains that attach to specific proteins produced by cancer cells. When these proteins are present, the tumour cells change colour under the microscope. IHC helps confirm whether certain biomarkers are present in the tumour.

Common biomarkers tested in adenocarcinoma of the lung

Your pathology report may include information about the following biomarkers. Each biomarker can help guide your treatment and provide important information about your tumour.

-

EGFR: Mutations (changes) in the EGFR gene are common in lung adenocarcinoma, particularly in individuals who have never smoked, women, and those of East Asian ancestry. Tumours with EGFR mutations often respond very well to targeted therapies called EGFR inhibitors. Your report will describe the tumour as EGFR-positive if a mutation is found. If no mutation is found, it will be called EGFR-negative.

-

ALK: Changes in the ALK gene, known as ALK rearrangements or fusions, lead to tumour growth and are often found in younger patients or non-smokers. Tumours with ALK gene rearrangements usually respond well to medications called ALK inhibitors. Your report will say your tumour is ALK-positive if this change is present. If it is not present, your tumour will be ALK-negative.

-

ROS1: ROS1 rearrangements (fusions) cause cancer cells to grow quickly. ROS1-positive tumours typically respond well to targeted ROS1 inhibitor therapies. If your tumour has a ROS1 rearrangement, it will be described as ROS1-positive. If no rearrangement is found, it will be described as ROS1-negative.

-

BRAF: Certain mutations in the BRAF gene can cause tumour cells to grow rapidly. Tumours with specific BRAF mutations, particularly the V600E mutation, can be treated with BRAF inhibitors. If a BRAF mutation is found, your tumour will be described as BRAF-positive. If no mutation is found, it will be called BRAF-negative.

-

MET: Mutations in the MET gene, especially mutations leading to “MET exon 14 skipping,” cause increased tumour growth. MET-positive tumours often respond to targeted therapies known as MET inhibitors. Your pathology report will describe your tumour as MET-positive if this mutation is present. If no mutation is found, your tumour will be MET-negative.

-

RET: RET rearrangements or fusions result in uncontrolled tumour growth. Tumours with RET fusions usually respond very well to RET inhibitors. Your report will state that your tumour is RET-positive if a fusion is found. If a fusion is not found, it will be described as RET-negative.

-

NTRK1-3: NTRK gene fusions are rare but can strongly promote tumour growth. Tumours with NTRK fusions usually respond to targeted medications known as TRK inhibitors. If an NTRK fusion is detected, your tumour will be described as NTRK-positive. If not, it will be described as NTRK-negative.

-

KRAS: KRAS mutations are common in lung adenocarcinomas, especially among smokers. Historically, KRAS-positive tumours were difficult to treat, but recent drugs targeting a specific KRAS mutation (KRAS G12C) have shown promising results. If a KRAS mutation is present, your tumour will be described as KRAS-positive. If no mutation is detected, your tumour is KRAS-negative.

-

ERBB2 (HER2): ERBB2 mutations (also known as HER2 mutations) can drive tumour growth, particularly in non-smokers. Tumours with HER2 mutations may respond to targeted therapies currently under investigation or available in specialized centres. If your tumour has an ERBB2 mutation, it will be described as ERBB2-positive. If no mutation is found, it will be ERBB2-negative.

-

NRAS: Mutations in the NRAS gene occur most commonly in tumours of people who have smoked. Currently, targeted therapies specific to NRAS mutations are limited; however, identifying this mutation can still aid in understanding tumour behaviour. Your tumour will be described as NRAS-positive if a mutation is found or NRAS-negative if no mutation is present.

-

MAP2K1 (MEK1): MAP2K1 mutations are more common among smokers and are associated with increased tumour growth. Currently, treatments specifically targeting MAP2K1 mutations are still being studied. Your pathology report will indicate if a MAP2K1 mutation is present (MAP2K1-positive) or not (MAP2K1-negative).

-

NRG1: NRG1 gene rearrangements are rare but significant because they can promote rapid tumour growth. Researchers are actively investigating targeted treatments for tumours with NRG1 rearrangements. Your tumour will be described as NRG1-positive if this rearrangement is found. If it is not found, it will be NRG1-negative.

Why are biomarker tests important for treatment?

Identifying these biomarkers in your tumour is essential because they help doctors choose the most effective treatments. Some biomarkers match specific drugs that directly target tumour cells. These treatments often work better and have fewer side effects than traditional chemotherapy.

If your tumour does not have biomarkers that match available targeted treatments, your doctor may recommend other options, such as chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Your medical team will help you understand your test results and the best treatment options available for you.

Treatment effect

Treatment effect is described in your report only if you received either chemotherapy or radiation therapy before surgery to remove the tumour. To determine the treatment effect, your pathologist will measure the amount of living (viable) tumour and express that number as a percentage of the original tumour. For example, if your pathologist finds 1 cm of viable tumour and the original tumour was 10 cm, the percentage of viable tumour is 10%.