by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

August 10, 2025

A malignant phyllodes tumour is a rare type of breast cancer that starts in the stroma (connective tissue) of the breast rather than the milk ducts or lobules. It is part of a group of tumours called fibroepithelial tumours, which have both stromal and epithelial (lining cell) components. The word phyllodes means “leaf-like” and refers to the way the stromal tissue grows into the epithelial-lined spaces inside the tumour.

Malignant phyllodes tumours are the most aggressive form in the phyllodes tumour spectrum, which also includes benign and borderline types. In malignant phyllodes tumours, the stromal cells look very abnormal under the microscope, grow quickly, and can spread to other parts of the body. Complete surgical removal is essential for treatment.

What are the symptoms of a malignant phyllodes tumour?

Most malignant phyllodes tumours present as a firm, painless lump in one breast. The lump often grows quickly over weeks or months and can become large enough to stretch or distort the skin. In some cases, the skin over the lump may become red, thin, or ulcerated. Rarely, there may be bloody nipple discharge.

Although most phyllodes tumours are not found in both breasts at the same time, they can occasionally occur in either breast. Large tumours can cause discomfort simply due to their size and weight.

What causes a malignant phyllodes tumour?

The exact cause is unknown. These tumours develop from the stromal cells that surround the ducts and lobules of the breast. Research has shown that some malignant phyllodes tumours have genetic changes in certain “cancer-related” genes such as TP53, EGFR, PIK3CA, and others.

Some tumours develop from pre-existing fibroadenomas or from previously benign or borderline phyllodes tumours that have undergone additional genetic changes. A small number of cases occur in people with rare inherited conditions such as Li–Fraumeni syndrome, which increases the risk for certain tumours.

How is the diagnosis of malignant phyllodes tumour made?

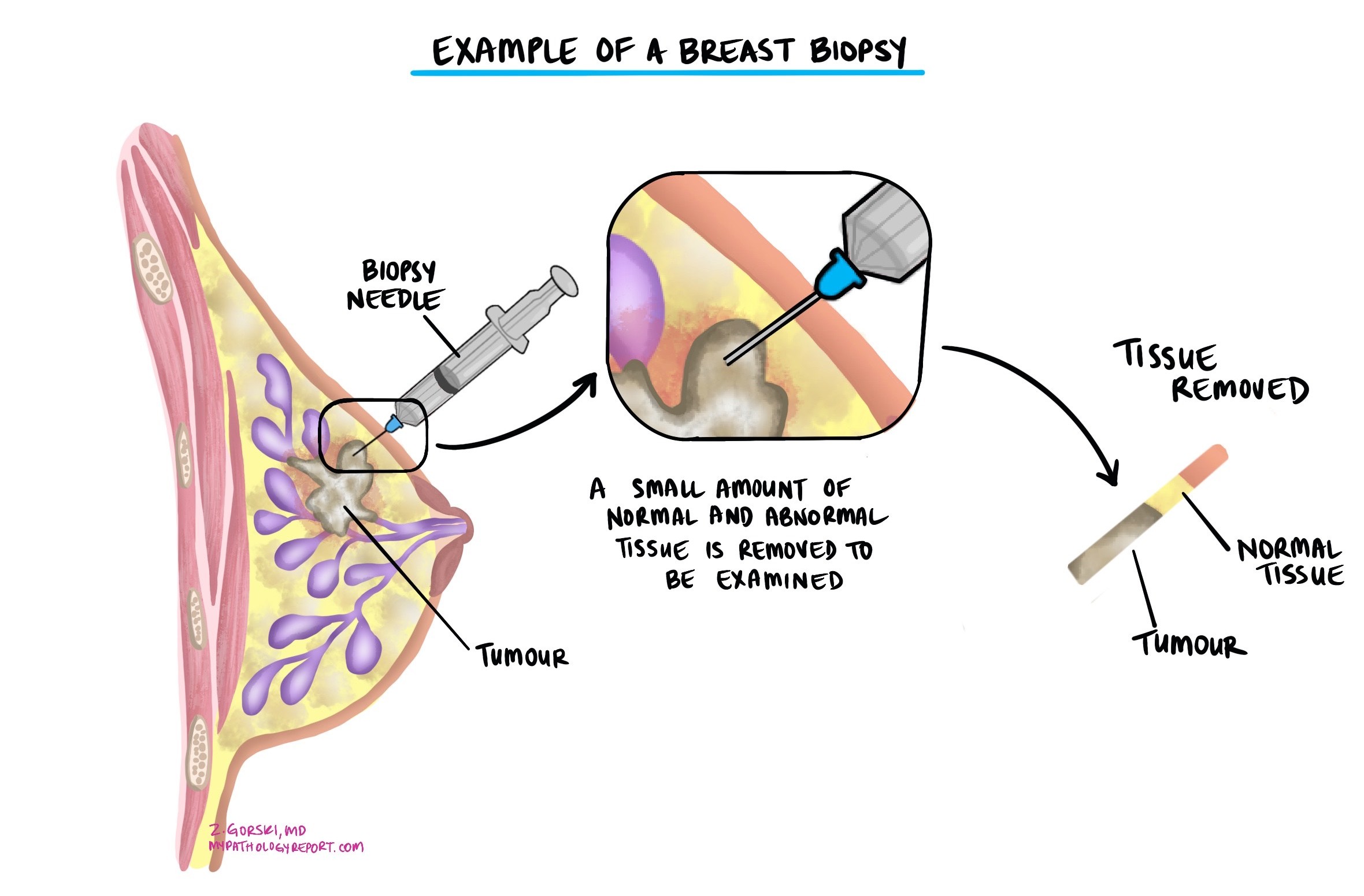

Diagnosis usually begins when a lump is found during a physical exam or on breast imaging such as mammography, ultrasound, or MRI. The only way to make a definite diagnosis is to examine tissue from the lump under the microscope. This can be done with a core needle biopsy, but because the features can overlap with benign or borderline phyllodes tumours and with fibroadenomas, the final diagnosis is often made after the whole lump is removed.

The pathologist examines the tumour for specific features such as how abnormal the stromal cells look, how many cells are actively dividing, whether there is stromal overgrowth (areas of stroma without any epithelial lining), and whether the tumour has infiltrative borders that grow into surrounding breast tissue. The presence of these features, especially in combination, supports a diagnosis of malignant phyllodes tumour.

How are phyllodes tumours classified?

Phyllodes tumours are classified into benign, borderline, and malignant types. This classification is based on:

-

Stromal cellularity – how many stromal cells are present.

-

Stromal atypia – how abnormal the stromal cells look.

-

Mitotic activity – how many cells are dividing.

-

Stromal overgrowth – whether there are areas with only stroma and no epithelial component.

-

Tumour border – whether the tumour pushes against surrounding tissue or infiltrates into it.

Malignant tumours show high stromal cellularity, marked atypia, high mitotic activity, stromal overgrowth, and infiltrative borders.

Margins

A margin is the edge of tissue removed with the tumour. Pathologists look at the margins under the microscope to see if any tumour cells are present at the cut edge.

-

Negative margins mean no tumour cells are at the edge, suggesting the tumour was completely removed.

-

Positive margins mean tumour cells are at the edge, increasing the risk that the tumour will come back in the same location.

For malignant phyllodes tumours, surgeons usually aim for a wide negative margin because this significantly reduces the risk of recurrence.

Can malignant phyllodes tumours spread?

Yes. While most phyllodes tumours behave locally, malignant phyllodes tumours can spread to distant sites. Spread usually occurs through the bloodstream rather than through the lymphatic system, and the lungs and bones are the most common locations for metastases. The risk of spread is still relatively low compared to many other breast cancers, but it is much higher than for benign or borderline phyllodes tumours.

Prognosis

The outlook for malignant phyllodes tumours depends on tumour size, whether it was completely removed, and whether it has spread. The most important factor for preventing recurrence is complete surgical excision with a wide margin. Recurrences often occur within the first few years after treatment and may be of the same or higher grade.

Although axillary lymph node involvement is rare, malignant phyllodes tumours can metastasize to other organs. Larger tumours and those containing unusual tissue types (called heterologous elements) are more likely to spread.

AJCC stage

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system categorizes malignant phyllodes tumors based on tumor size (T category), lymph node involvement (N category), and distant spread (M category):

T category (Tumor size)

- pT1: The tumor measures 5 cm or less in greatest dimension.

- pT2: The tumor is larger than 5 cm but no more than 10 cm.

- pT3: The tumor is larger than 10 cm but no more than 15 cm.

- pT4: The tumor is larger than 15 cm.

N category (Lymph node involvement)

- pN0: No regional lymph node involvement.

- pN1: Cancer cells have spread to regional lymph nodes.

M category (Distant metastasis)

- pM0: No distant spread.

- pM1: Cancer cells have spread to distant organs, such as the lungs or bones.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

Was my tumour completely removed and were the margins negative?

-

What features under the microscope indicated that my tumour was malignant?

-

Do I need any additional treatment beyond surgery?

-

What is my risk of the tumour coming back or spreading?

-

How often should I have follow-up visits and imaging?

-

Should my family history be reviewed for genetic conditions such as Li–Fraumeni syndrome?

-

What symptoms should I watch for that might indicate recurrence or spread?