by Allison Osmond, MD FRCPC

June 7, 2023

What is Merkel cell carcinoma?

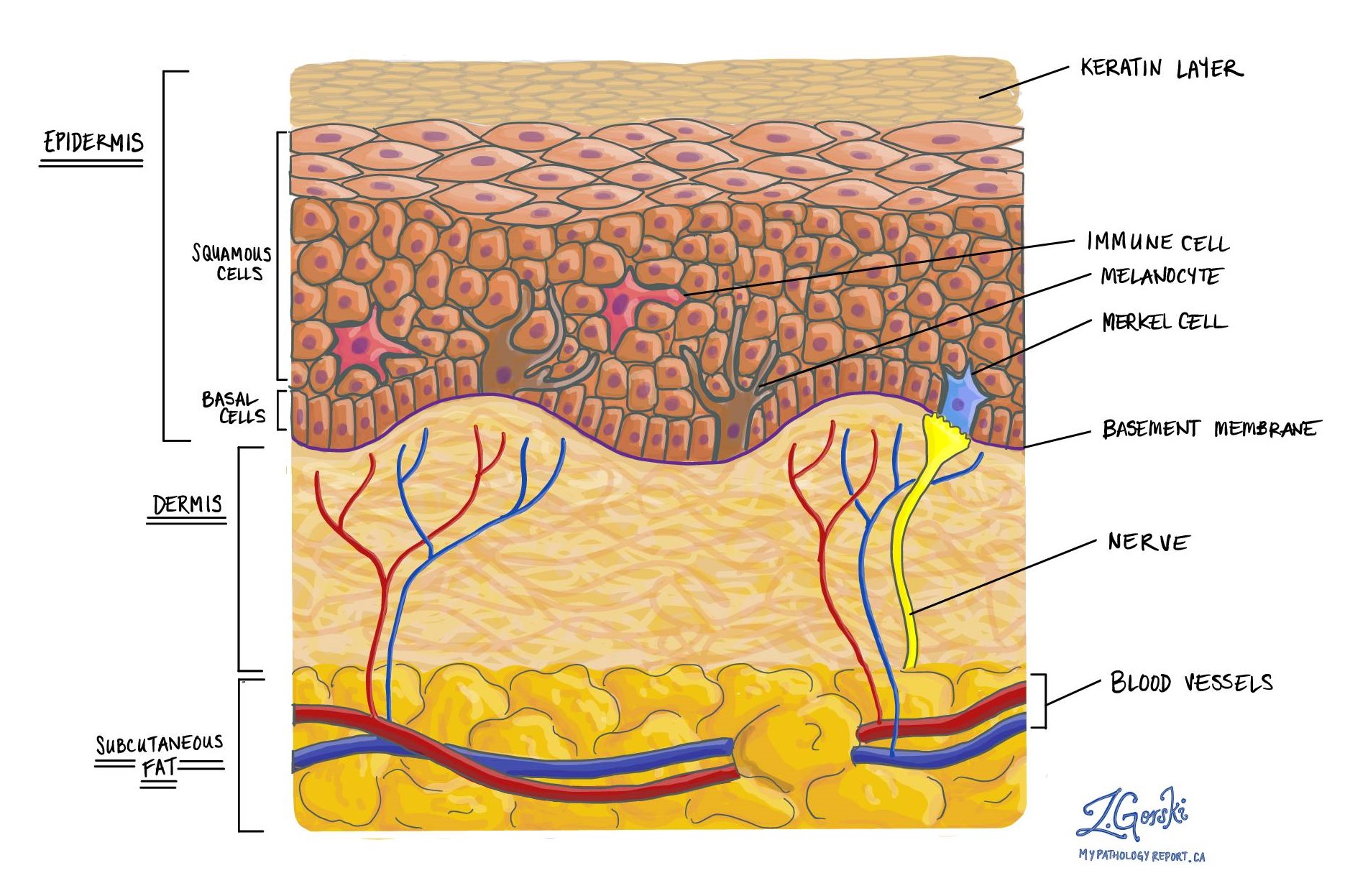

Merkel cell carcinoma is a type of skin cancer. It develops from the Merkel cells normally found in the skin. Merkel cells are neuroendocrine cells and Merkel cell carcinoma is a type of neuroendocrine tumour. For this reason, another name for Merkel cell carcinoma is primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin.

What causes Merkel cell carcinoma?

Merkel cell carcinoma usually occurs in older individuals who have a history of prolonged exposure to sun and sunburns. However, Merkel cell carcinoma can also occur in younger patients and this is commonly seen in people who have weakened immune systems for a variety of reasons. In younger patients, a virus called Polyomavirus is believed to play a role in the development of Merkel cell carcinoma.

How do pathologists make this diagnosis?

The diagnosis is usually made after a small tissue sample is removed in a procedure called a biopsy. The diagnosis can also be made after the entire tumour is removed in a procedure called an excision. If the diagnosis is made after a biopsy, your doctor will probably recommend a second surgical procedure to remove the rest of the tumour.

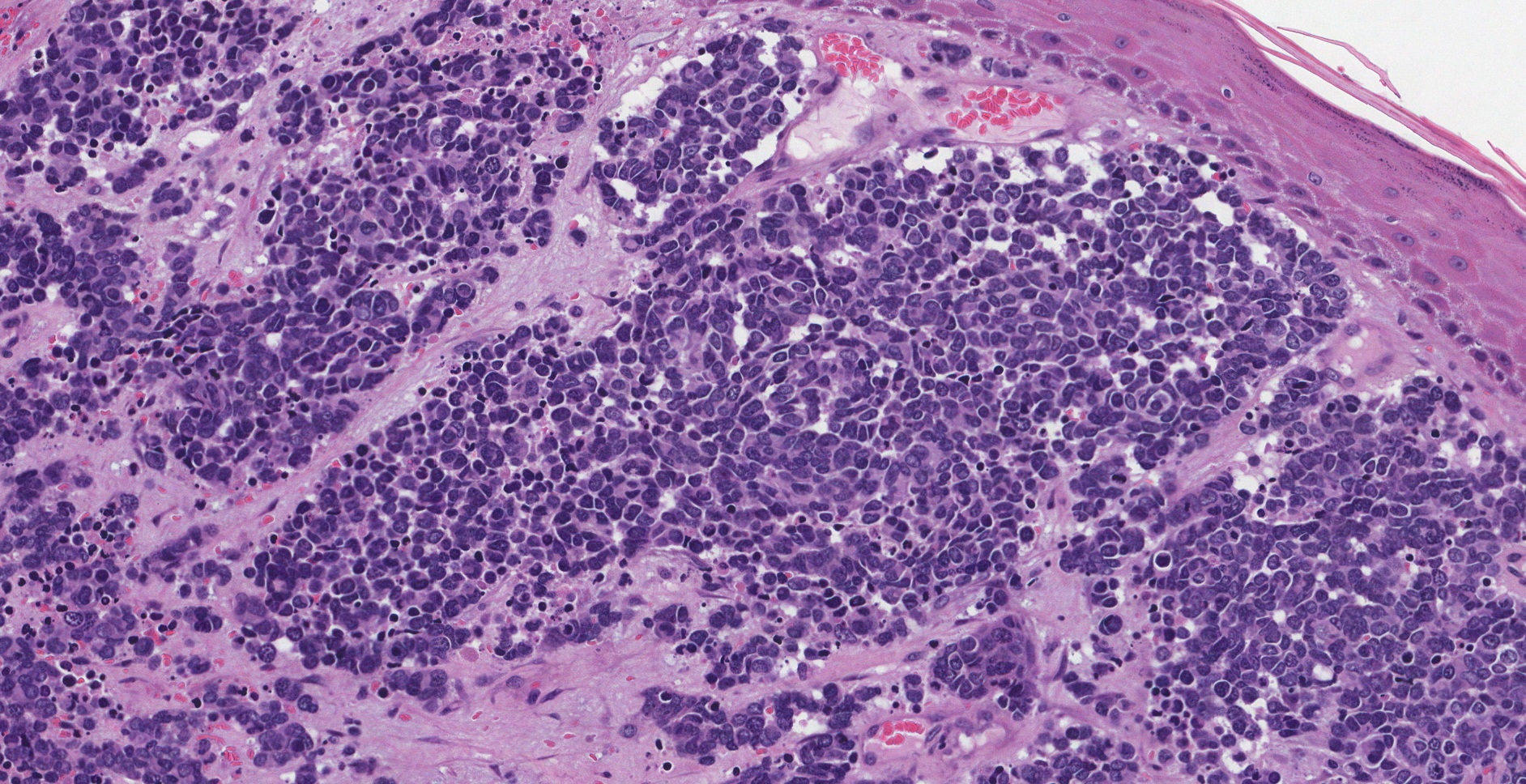

Normal Merkel cells are long and skinny and they are not easily seen through the microscope. However, in Merkel cell carcinoma, the abnormal Merkel cells increase both in size and in number which allows your pathologist to easily see them through the microscope.

Tumour size

This is the size of the tumour measured in centimetres. Your report may only describe the greatest dimension. For example, if the tumour measures 5.0 cm by 3.2 cm by 1.1 cm, the report may describe the tumour size as 5.0 cm in the greatest dimension.

The tumour size is used to determine the tumour stage (see Pathologic stage below). Tumours that are larger than 2 centimetres are more likely to re-grow after treatment or to spread to other areas of the body.

Depth of invasion (tumour thickness)

All Merkel cell carcinomas start in the epidermis on the outer surface of the skin. Depth of invasion describes how far the cancer cells have travelled from the epidermis into the tissue below. The movement of cancer cells from the epidermis into the tissue below is called invasion.

The depth of invasion is measured from the surface of the skin to the deepest point of invasion. The depth of invasion is measured in millimetres (mm). Tumours with a greater depth of invasion are more likely to spread to other parts of the body. The depth of invasion is also used to determine the tumour stage (see Pathologic stage below). Some reports use the term tumour thickness to describe the depth of invasion.

Tumour extension

Large tumours can grow beyond the skin into bone, muscle, or cartilage. Pathologists will use tumour extension to describe tumours that have grown into any of these types of tissue. Tumour extension into bone, muscle, or cartilage is associated with an increased risk that the tumour will spread to other parts of the body or will re-grow in the same location after treatment. Tumour extension is also used to determine the tumour stage (see Pathologic stage below).

Tumour pattern of growth

Pathologists use the term pattern of growth is used to describe how the cancer cells look when examined under the microscope.

For Merkel cell carcinoma, there are two main patterns of growth:

- Nodular – The cancer cells are growing in one large group.

- Infiltrative – The cancer cells are growing as long lines of cancer cells. This pattern can look like a spider’s web when examined under a microscope.

Tumours that grow in a nodular pattern tend to be associated with a better prognosis compared to tumours that grow in an infiltrative pattern.

Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes

Lymphocytes are specialized cells that are part of the body’s immune system. Lymphocytes respond to infections, injury, or cancer. Lymphocytes are frequently found in the tissue around Merkel cell carcinoma and their presence is considered a sign that the body is attempting to prevent the spread of the disease.

There are two ways to describe the lymphocytes around the tumour:

- Brisk – This means that lots of lymphocytes were seen in and around the tumour.

- Non-brisk – This means that very few lymphocytes were seen around the tumour.

Non-brisk tumour infiltrating lymphocytes is associated with a worse prognosis.

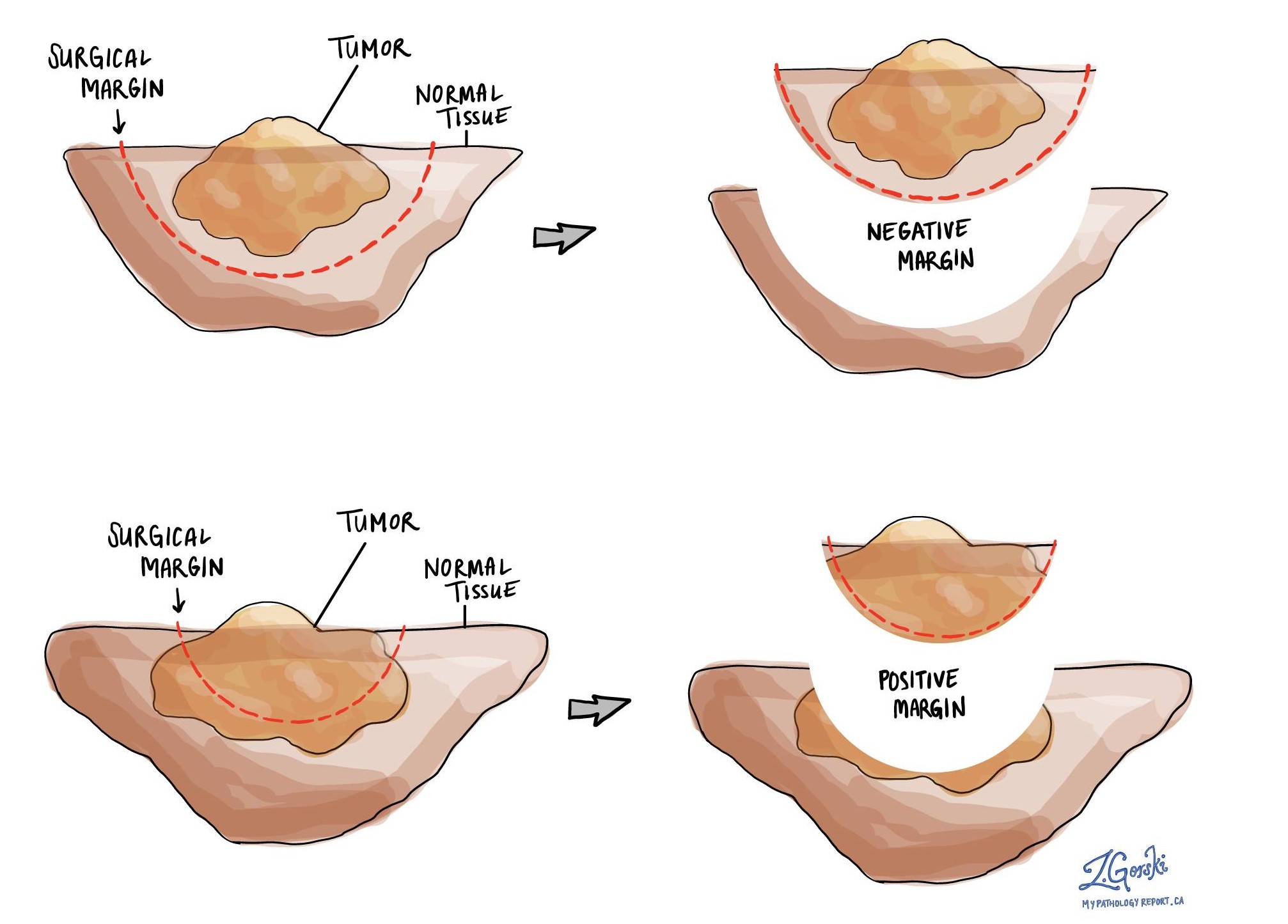

Margins

A margin is the normal tissue that surrounds a tumour and is removed with the tumour at the time of surgery. In most cases, surgeons will try to remove 1 cm of normal tissue around the entire tumour.

The normal skin surrounding the tumour is called the peripheral margin while the tissue below the tumour is called the deep margin. Both margins are closely examined under the microscope to see if there are any cancer cells in the normal-looking tissue.

If no cancer cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue the margin is called negative. If cancer cells are seen at the very edge of the cut tissue, the margin is called positive. A positive margin is important because it is associated with a greater risk that the tumour will come back in the same location (local recurrence) after treatment.

Mitotic rate

Cells divide in order to create new cells. This process is called mitosis. Pathologists frequently count the number of mitoses in a tumour and this count is called the mitotic rate. Most pathology reports describe the mitotic rate as the number of mitotic cells per millimetre square. The mitotic rate is important because tumours with more mitotic figures are more likely to spread to other parts of the body.

Lymphovascular invasion

Blood moves around the body through long thin tubes called blood vessels. Another type of fluid called lymph which contains waste and immune cells moves around the body through lymphatic channels.

Cancer cells can use blood vessels and lymphatics to travel away from the tumour to other parts of the body. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to another part of the body is called metastasis. Before cancer cells can metastasize, they need to enter a blood vessel or lymphatic. This is called lymphovascular invasion. Lymphovascular invasion increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in a lymph node or a distant part of the body such as the lungs.

In-transit metastasis

Cancer cells that leave the main tumour and travel to another part of the body are called metastasis. Cancer cells often travel to a lymph node which is called a lymph node metastasis (see Lymph nodes below). Merkel cell carcinoma cancer cells that are found in between the main tumour and a lymph node are called in-transit metastasis. The finding of an in-transit metastasis is important because it increases the nodal stage (see Pathologic stage below) and is associated with a worse prognosis.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs located throughout the body. Cancer cells can travel from the tumour to a lymph node through lymphatic channels located in and around the tumour (see Lymphovascular invasion above). The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to a lymph node is called metastasis.

If your tumour was located on your face or head, lymph nodes from the neck are sometimes removed at the same time as the main tumour in a procedure called a neck dissection. The lymph nodes removed usually come from different areas of the neck and each area is called a level. The levels in the neck include 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Lymph nodes on the same side as the tumour are called ipsilateral while those on the opposite side of the tumour are called contralateral.

A sentinel lymph node is the closest lymph node to the tumour. When Merkel cell carcinoma travels to a lymph node, it usually goes to the sentinel node first. All other lymph nodes in the area of the tumour are simply referred to as regional lymph nodes. Your pathology report will specify which lymph nodes are involved.

Most reports include the total number of lymph nodes examined and the number that contain cancer cells. Lymph nodes that contain cancer cells are often called positive while those that do not contain any cancer cells are called negative.

Your pathologist may use special tests such as immunohistochemistry in order to see if there are any cancer cells in the examined lymph nodes. For example, Merkel cells make proteins called cytokeratins and immunohistochemistry is can help pathologists see cells that make cytokeratins.

Lymph nodes are used to determine the nodal stage (see Pathologic stage below). Your doctors will use the nodal stage together with the tumour stage to determine the best treatment options for you.

Pathologic stage

The pathologic stage for Merkel cell carcinoma is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system originally created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT) for Merkel cell carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma is given a tumour stage between 1 and 4 based on the size of the tumour and whether or not the tumour grows into other tissues like bone, muscle, fascia or cartilage.

- T1 – The tumour is no larger than 2 cm.

- T2 – The tumour is greater than 2 cm but no larger than 5 cm.

- T3 – The tumour is greater than 5 cm but does not extend into any other types of tissue below the skin.

- T4 – The tumour extends into bone, muscle, fascia, or cartilage.

Nodal stage (pN) for Merkel cell carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma is given a nodal stage of 0 to 3 based on the presence of cancer cells in a lymph node and in-transit metastases.

- No – No cancer cells were seen in any of the lymph nodes examined.

- N1 – Cancer cells are seen in a lymph node.

- N2 – Cancer cells are seen outside of the main tumour but not in a lymph node (in-transmit metastases).

- N3 – Cancer cells are seen in a lymph node AND outside of the main tumour (in-transit metastases).

If no lymph nodes are sent for pathological examination, the nodal stage cannot be determined and the nodal stage is listed as pNX.

Metastatic stage (pM) for Merkel cell carcinoma:

Merkel cell carcinoma is given a metastatic stage of M0 or M1 based on the presence of cancer cells outside of the main tumour. Cancer cells that have travelled to a distant body site are also considered metastatic disease but are given a lower metastatic stage than cancer cells that have travelled to the lungs.

The metastatic stage can only be determined if tissue from a distant site is sent for pathological examination. Because this tissue is rarely present, the metastatic stage cannot be determined and is listed as pMX.