by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

January 19, 2024

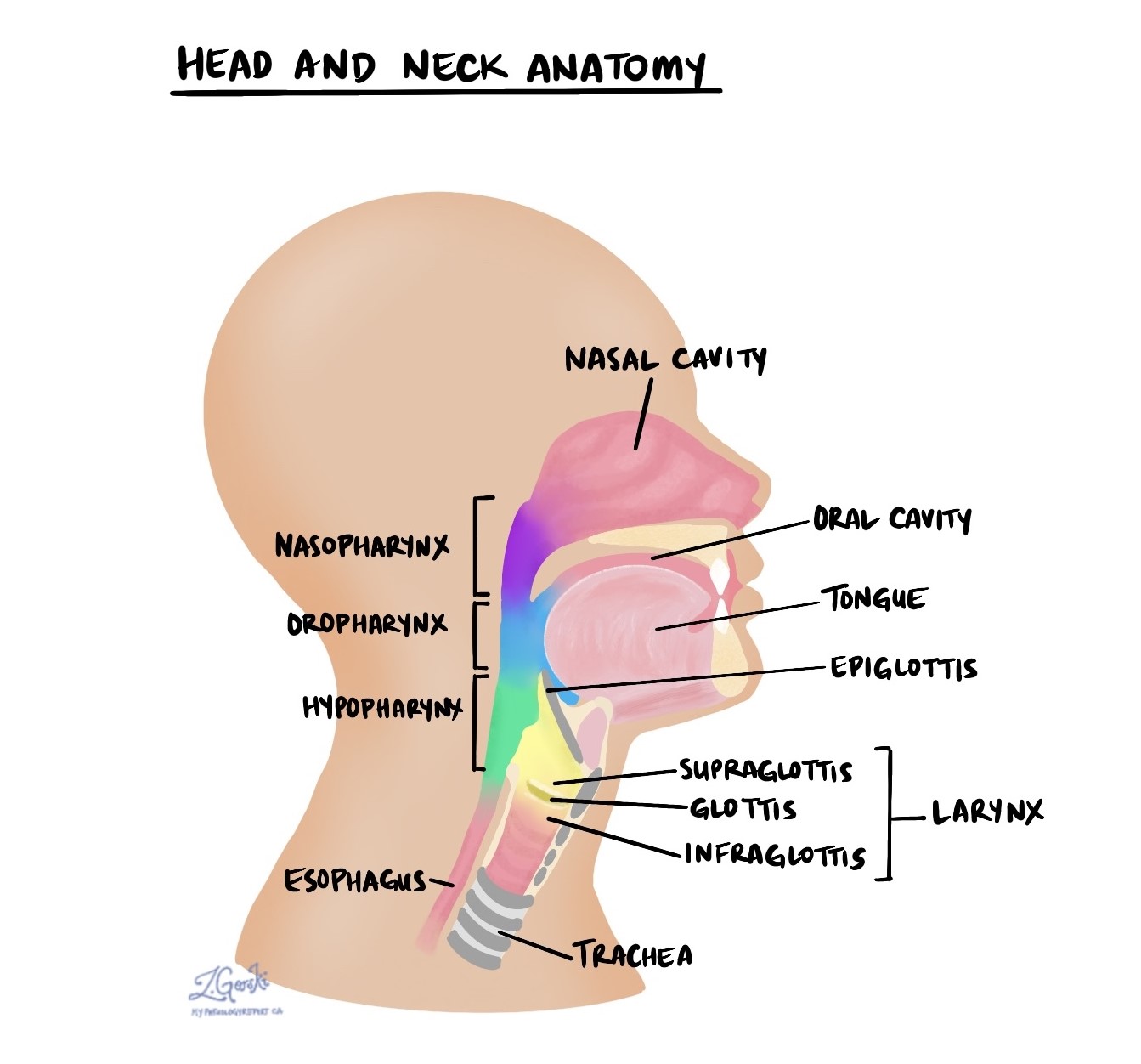

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is a type of cancer that starts from an area at the back of the nose and throat called the nasopharynx. Subtypes of nasopharyngeal carcinoma include non-keratinizing, keratinizing, and basaloid. Most cases of non-keratinizing type and basaloid type nasopharyngeal carcinoma are caused by a virus known as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) which infects the cells on the inside of the nasopharynx and causes them to change into cancer cells. In contrast, keratinizing-type nasopharyngeal carcinoma is typically caused by cigarette smoking and excess alcohol consumption.

Types of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

There are three types of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: non-keratinizing, keratinizing, and basaloid. The type can only be determined after the tumour is examined under the microscope by a pathologist.

Non-keratinizing type

The non-keratinizing type is the most common type of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The tumour is made up of large abnormal-looking tumour cells that are frequently surrounded by specialized immune cells called lymphocytes. This type of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is almost always associated with EBV. Another name for this type of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx.

Keratinizing type

The keratinizing type of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is much less common than the non-keratinizing type. The tumour is made up of large abnormal-looking tumour cells that look pink because they are full of a protein called keratin. This type of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is usually associated with cigarette smoking or excessive alcohol consumption. Another name for this type of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx.

Basaloid type

The basaloid type of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is the least common. The tumour is made up of large blue cells. Most basaloid-type tumours are associated with EBV, however, some are associated with other factors such as cigarette smoking. Another name for this type of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is usually made after a small sample of tissue is removed from your body in a procedure called a biopsy. The tissue is then sent to a pathologist who examines it under a microscope.

Your pathologist may perform a test called immunohistochemistry to confirm the diagnosis. This test allows your pathologist to ‘see’ specific types of proteins inside the tumour cells. When immunohistochemistry is performed, the tumour cells in nasopharyngeal carcinoma are usually positive for pan-cytokeratin and high-molecular-weight keratins such as CK5. The tumour cells are usually negative for other keratins such as CK7 and CK20.

EBER

Cells infected by EBV produce a chemical called Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA or EBER for short. Pathologists use a special test called in situ hybridization (ISH) to look for cells that are producing EBER. Your report will describe the tumour as positive if EBER is seen inside the cancer cells and negative if no EBER is seen. Most nasopharyngeal carcinomas are positive for EBER.

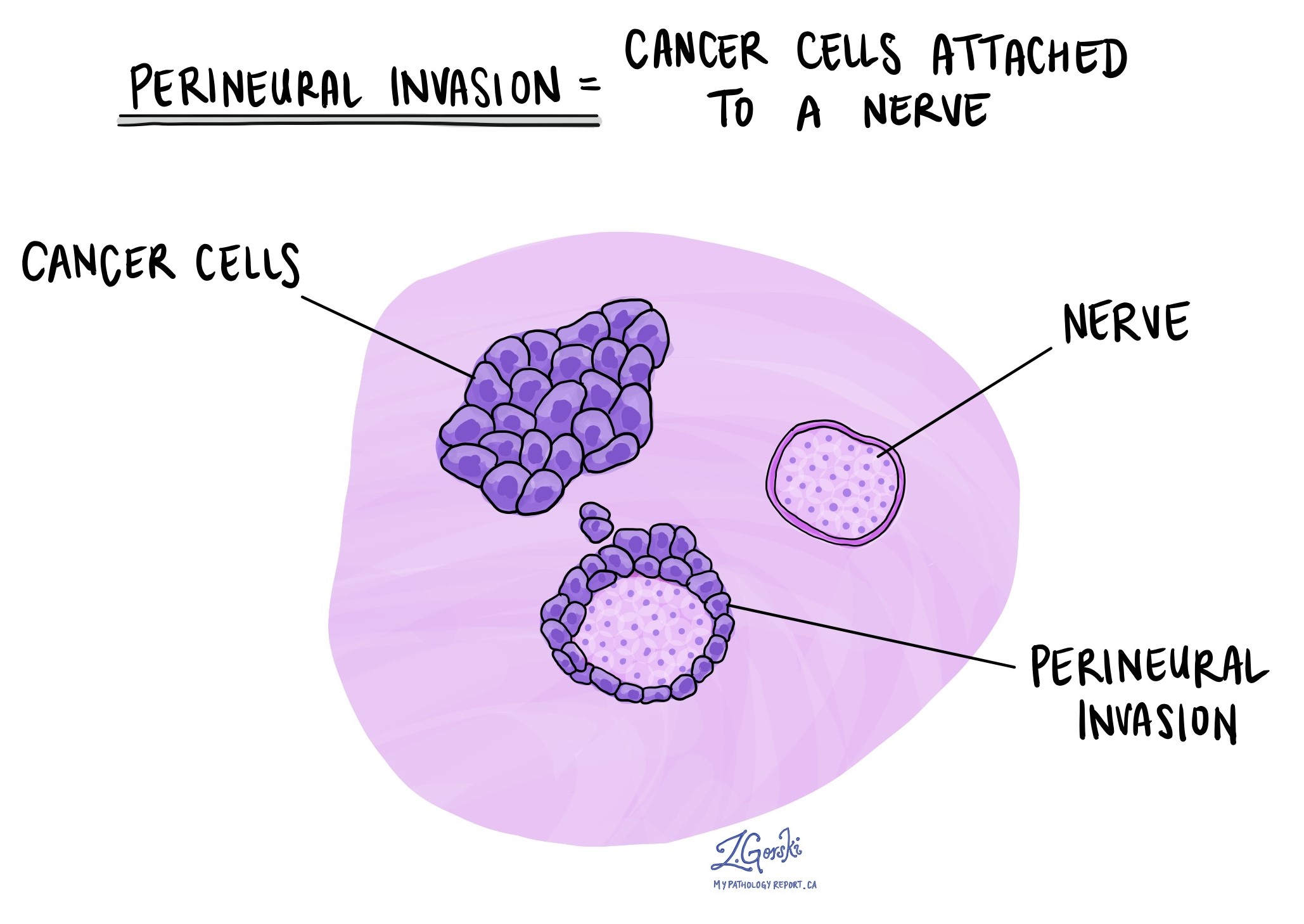

Perineural invasion

Pathologists use the term “perineural invasion” to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that specifically refers to cancer cells found inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. The presence of perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic channel. Blood vessels, thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, contrast with lymphatic channels, which carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic channels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes, scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it enables cancer cells to spread to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the lungs, via the blood or lymphatic vessels.

Margins

In pathology, a margin refers to the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure like an excision or resection, aimed at removing the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are present at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was fully removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour to lymph nodes through small lymphatic vessels. For this reason, lymph nodes are commonly removed and examined under a microscope to look for cancer cells. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to another part of the body such as a lymph node is called a metastasis.

Cancer cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour although lymph nodes far away from the tumour can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are only typically removed if they are enlarged and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancer cells in the lymph node.

A neck dissection is a surgical procedure performed to remove lymph nodes from the neck. The lymph nodes removed usually come from different areas of the neck and each area is called a level. The levels in the neck include 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Your pathology report will often describe how many lymph nodes were seen in each level sent for examination. Lymph nodes on the same side as the tumour are called ipsilateral while those on the opposite side of the tumour are called contralateral.

If any lymph nodes were removed from your body, they will be examined under the microscope by a pathologist and the results of this examination will be described in your report. “Positive” means that cancer cells were found in the lymph node. “Negative” means that no cancer cells were found. If cancer cells are found in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) may also be included in your report. Extranodal extension means that the tumour cells have broken through the capsule on the outside of the lymph node and have spread into the surrounding tissue.

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy is required.

Pathologic stage

Tumour stage (pT)

This tumour is given a tumour stage between 1 and 4. The tumour stage is based on how far the tumour has spread outside of the nasopharynx.

- T1 – The tumour is only seen in the nasopharynx OR it has only spread to the oropharynx or nasal cavity.

- T2 – The tumour has spread outside of the nasopharynx into the soft tissues or muscles that surround the nasopharynx.

- T3 – The tumour has spread into the bones of the skull, the sinuses, or the bones of the spine.

- T4 – The tumour has spread to the eyes, the large nerves of the head known as the cranial nerves, the parotid gland, or beyond the skull into the cranial cavity (the cavity that holds the brain).

Nodal stage (pN)

This tumour is given a nodal stage between 0 and 3 based on the number of lymph nodes that contain tumour cells, the size of the largest tumour deposit, and the location of the lymph nodes with tumour cells.

- N0 – No tumour cells were found in any of the lymph nodes examined.

- N1 – Tumour cells were found in one or more lymph nodes but the size of the tumour deposit was not larger than 6 centimetres.

- N2 – Tumour cells were found in lymph nodes on both sides of the neck (bilateral lymph nodes) but the size of the tumour deposit was not larger than 6 centimetres.

- N3 – Tumour cells were found in a lymph node and the size of the tumour deposit was larger than 6 centimetres.