By Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

August 27, 2025

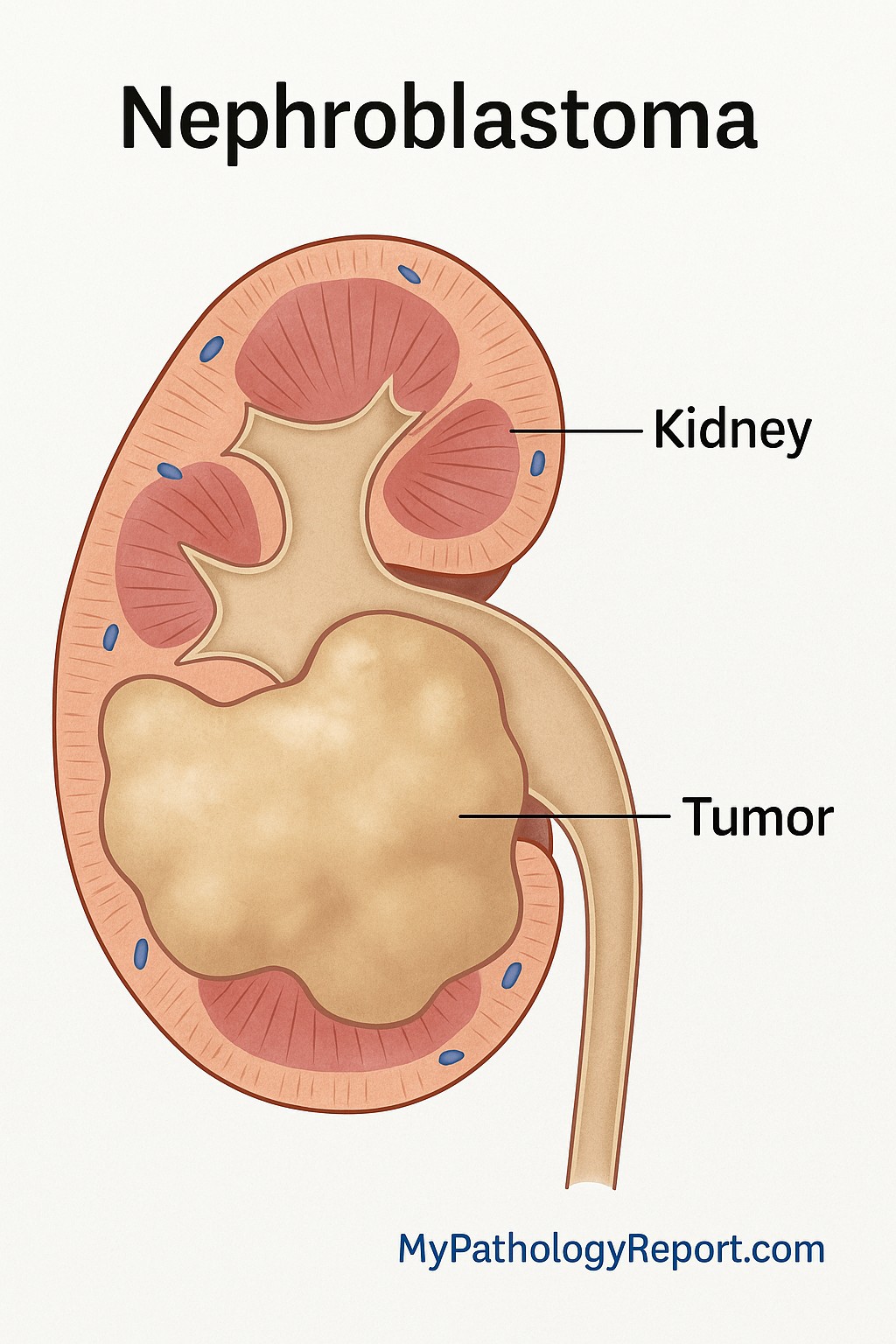

Nephroblastoma, also called Wilms tumor, is a type of cancer that starts in the kidney. It is the most common kidney cancer in children. The tumor develops from early kidney cells called nephrogenic blastema, which normally form during development in the womb. Under the microscope, nephroblastoma looks similar to a developing kidney.

How common is nephroblastoma?

Nephroblastoma is most often diagnosed in children between the ages of 3 and 4. It is slightly more common in girls than in boys. It affects about 1 in 10,000 children in Europe and North America. The tumor is more common in African and African-American children and less common in children from eastern Asian populations. Nephroblastoma rarely occurs in adults.

Where does nephroblastoma occur?

Nephroblastoma develops in the kidney. In most children, only one kidney is affected. In about 5 to 10 percent of cases, both kidneys are involved. Very rarely, nephroblastoma may develop outside of the kidney.

What are the symptoms of nephroblastoma?

The most common sign of nephroblastoma is a mass or swelling in the abdomen that is often first noticed by a parent or caregiver. About 20 to 30 percent of children also develop other symptoms, which may include:

-

Abdominal pain.

-

Blood in the urine (called hematuria).

-

High blood pressure due to increased hormone production.

-

Low red blood cell count (anemia), which can cause tiredness and weakness.

Are some children more likely to develop nephroblastoma?

Yes. In 10 to 15 percent of cases, nephroblastoma is associated with certain genetic conditions or syndromes. These syndromes can increase the risk of developing the tumor.

High risk syndromes (greater than 20 percent):

-

WAGR syndrome (Wilms tumor, absence of the iris in the eye, genitourinary abnormalities, and developmental delays).

-

Denys–Drash syndrome.

Moderate risk syndromes (5 to 20 percent):

-

Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome.

-

Simpson–Golabi–Behmel syndrome.

-

Frasier syndrome.

Low risk syndrome (less than 5 percent):

-

Bloom syndrome.

-

DICER1 syndrome.

-

Li–Fraumeni syndrome.

-

Isolated hemihypertrophy (where one side of the body grows larger than the other).

In addition, about 1 to 2 percent of cases occur in families with a history of nephroblastoma.

What causes nephroblastoma?

Nephroblastoma is thought to develop from small clusters of abnormal kidney cells called nephrogenic rests. These are seen in about 40 percent of children with tumors in one kidney and in more than 90 percent of children with tumors in both kidneys.

There are different types of nephrogenic rests. Some remain dormant, while others grow abnormally. When many nephrogenic rests are present, the condition is called nephroblastomatosis. Most children with nephroblastomatosis do not develop cancer, but in certain cases, such as infants with a specific type called perilobar nephrogenic rests, there is a much higher risk of developing a tumor in the other kidney.

Several genes play a role in the development of nephroblastoma, including the WT1 gene on chromosome 11. Changes in other genes, such as CTNNB1, IGF2, TP53, and MYCN, can also be involved.

How is nephroblastoma treated?

There are two main treatment approaches to nephroblastoma used worldwide:

-

International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) – This approach, followed in most countries, starts with chemotherapy to shrink the tumor before surgery. Surgery is then performed, followed by more chemotherapy and sometimes radiation therapy.

-

Children’s Oncology Group (COG) – This approach, followed mainly in the United States and Canada, usually begins with surgery to remove the tumor, followed by chemotherapy and sometimes radiation therapy.

A biopsy (a small tissue sample) before treatment is generally not recommended unless the child has an unusual presentation, such as being older than 10 years at diagnosis.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of nephroblastoma is usually made after a combination of imaging tests, surgery, and microscopic examination by a pathologist.

-

Imaging tests such as ultrasound, CT, or MRI are often the first step. These scans can show a mass in the kidney and help doctors decide whether the findings are most consistent with nephroblastoma or another tumor.

-

Surgery is usually performed to remove the tumor, either before or after chemotherapy depending on the treatment approach. The tumor is then sent to the pathology laboratory.

-

Microscopic examination is the most important step in making the diagnosis. A pathologist examines thin slices of the tumor under the microscope to look for the three typical components: blastemal, epithelial, and stromal cells. The presence of at least two of these components confirms the diagnosis in most cases.

-

Special tests, such as immunohistochemistry or molecular testing, may also be performed to detect proteins and gene changes that are characteristic of nephroblastoma.

Together, these steps allow doctors to make a precise diagnosis and plan the best treatment.

What does nephroblastoma look like under the microscope?

Nephroblastoma is often made up of three main components:

-

Blastemal cells – These are small, immature cells that resemble early kidney tissue.

-

Epithelial cells – Cells forming tubules, papillae, or glomerulus-like structures (kidney filtering units).

-

Stromal tissue – Connective tissue that may show muscle, fat, or cartilage-like changes.

Not all tumors contain all three components. Some contain only one or two.

A special feature called anaplasia is seen in about 7 to 10 percent of nephroblastomas. Anaplasia means the tumor cells are much larger and more abnormal than usual, with distorted dividing figures. Anaplasia is divided into focal (limited areas) and diffuse (spread throughout the tumor). Diffuse anaplasia is linked with worse outcomes.

What other tests may be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

Pathologists may use a test called immunohistochemistry (IHC) to confirm the diagnosis of nephroblastoma. IHC uses special stains to look for proteins inside the tumor cells.

-

Blastemal cells are usually positive for WT1, PAX8, and vimentin.

-

Epithelial cells are positive for cytokeratin, EMA, and CD56. They may also show WT1.

-

Stromal cells are positive for vimentin and sometimes for BCL2 or CD34.

The protein WT1 is especially important because it is present in about 90 percent of nephroblastomas. This pattern of results helps pathologists confirm that the tumor is nephroblastoma and not another type of childhood kidney cancer.

How do doctors classify nephroblastoma?

Classification means grouping tumors based on their appearance under the microscope. Classification is important for nephroblastoma because it helps predict how the tumor will behave and how much treatment is needed. There are two main classification systems although their use varies by location.

SIOP histologic classification

This system classifies the tumor after chemotherapy has been given before surgery. It is used in Europe and in many other countries outside North America.

Low risk

- Tumors that are completely destroyed by chemotherapy (completely necrotic).

- Cystic tumors with partly differentiated cells.

Intermediate risk

- Tumors with a mix of epithelial, stromal, or regressive (partially destroyed) cells.

- Tumors with focal anaplasia (small, limited areas of abnormal cells).

High risk

- Tumors with mostly blastemal cells (very immature cells) after chemotherapy.

- Tumors with diffuse anaplasia (widespread abnormal, aggressive cells).

COG histologic classification

This system classifies the tumor before chemotherapy, because surgery is done first. This system is used primarily in the United States and Canada.

Favorable histology

- Tumors without anaplasia.

- These tumors respond very well to treatment.

Unfavorable histology

- Tumors with diffuse anaplasia.

- These tumors are more difficult to treat and require stronger therapy.

How do doctors stage nephroblastoma?

Staging describes how far the tumor has spread at the time of diagnosis. Staging is important because it guides treatment and helps predict prognosis. Both SIOP and COG use similar stages, but there are small differences.

Stage I

-

Tumor is limited to the kidney.

-

Completely removed with surgery.

-

No spread outside the kidney.

Stage II

-

Tumor has grown into tissues just outside the kidney, such as fat or the renal sinus.

-

Still completely removable with surgery.

Stage III

-

Tumor cannot be completely removed, or tumor cells are found at the edges of the removed tissue.

-

Tumor cells may be found in nearby lymph nodes or blood vessels.

-

Tumor rupture or spillage into the abdomen places the tumor in this stage.

Stage IV

-

Tumor has spread (metastasized) to distant organs such as the lungs, liver, bone, or brain.

-

Tumor cells may also be found in lymph nodes far from the kidney.

Stage V

-

Tumors are present in both kidneys at the time of diagnosis.

-

Each kidney is staged separately.

What is the prognosis for nephroblastoma?

The outlook for children with nephroblastoma is generally very good. With modern treatment, about 90 percent of children survive. Most relapses, when they occur, happen within the first two years after diagnosis.

Features linked with a good prognosis

-

Stage I or II tumors that are limited to the kidney or nearby tissues and completely removed with surgery.

-

No anaplasia (called favorable histology).

- Age younger than 2 years with a small, low-stage tumor.

-

Tumor weight less than 550 grams.

-

Lung nodules that shrink quickly after the first rounds of chemotherapy.

-

No high-risk genetic changes in the tumor.

Features linked with a worse prognosis

-

Stage III tumors that involve nearby lymph nodes, rupture, or cannot be fully removed.

-

Stage IV tumors that have spread to distant organs such as the lungs, liver, bone, or brain.

-

Stage V tumors affecting both kidneys, which makes surgery more complicated.

-

Diffuse anaplasia (widespread abnormal, aggressive cells).

-

Age older than 4 years, especially older than 10 years.

-

Large, heavy tumors weighing more than 550 grams.

-

Lung nodules that do not shrink quickly with initial chemotherapy.

-

Genetic changes such as loss of heterozygosity at chromosomes 1p and 16q or 1q gain, which are linked to a higher risk of recurrence.

Questions to ask your doctor

- What stage is the tumor?

-

Did the tumor show anaplasia or other high-risk features?

-

Which treatment approach is being used (SIOP or COG)?

-

Will my child need chemotherapy, radiation, or both?

-

Is genetic testing recommended for my child or family?

-

What follow-up care will be needed after treatment?