by Allison Osmond, MD FRCPC

December 9, 2024

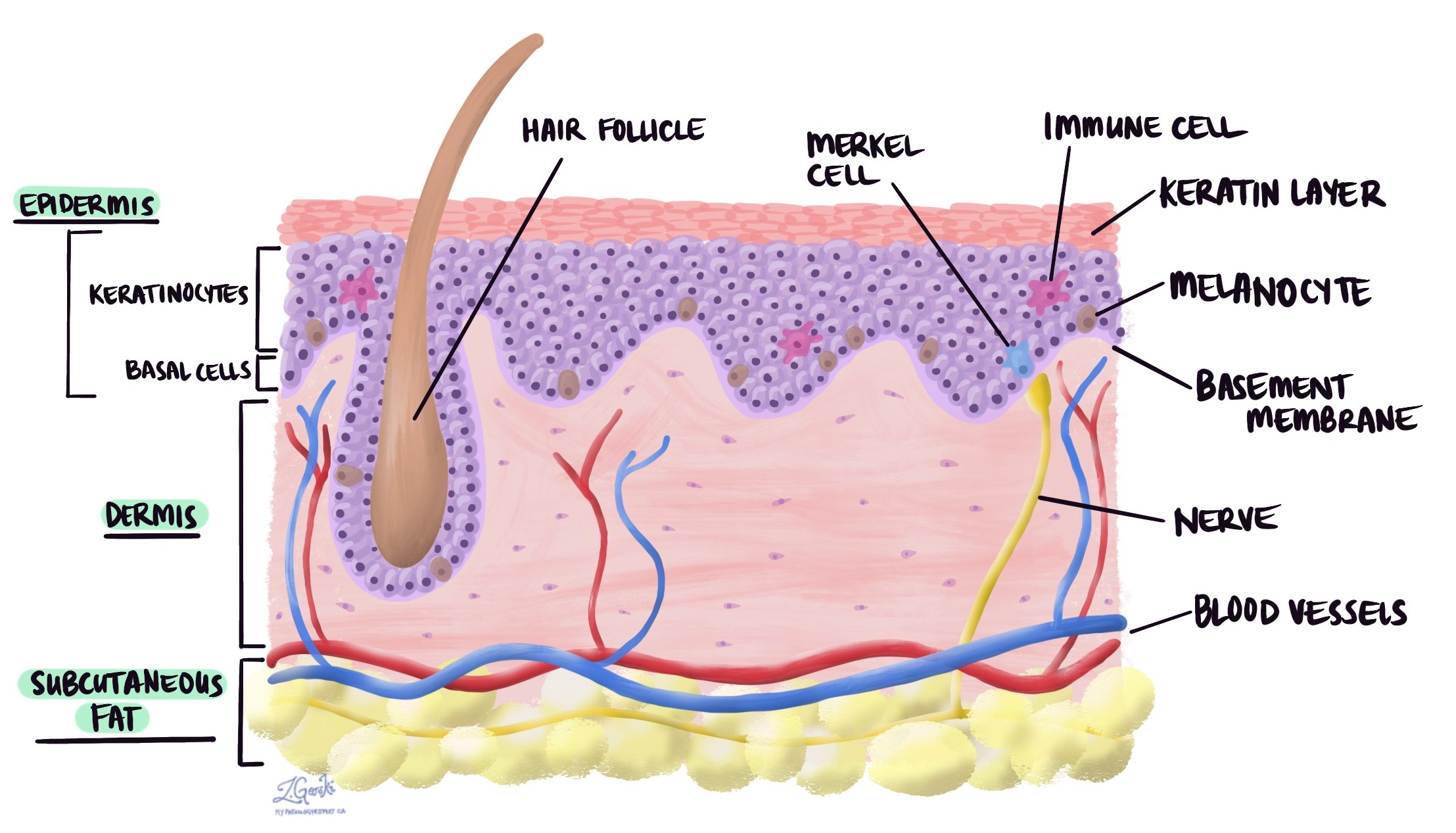

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common type of skin cancer. It develops from basal cells, which are found in the outer layer of the skin (the epidermis) and in hair follicles. While different types of basal cell carcinoma have unique appearances under the microscope and on the skin, they share similar causes and risk factors. These tumours grow slowly and rarely spread to other body parts, but they can invade and damage nearby tissues if left untreated.

Under the microscope, all basal cell carcinomas show clusters of small, darkly stained cells (called basaloid cells) with very little surrounding cytoplasm.

What are the symptoms of basal cell carcinoma?

Basal cell carcinoma often appears as a small, painless bump or patch on the skin that slowly grows over time. The appearance of basal cell carcinoma can vary depending on the type but may include:

- A shiny or pearly bump, often with visible blood vessels

- A flat, scaly, or reddish patch on the skin

- A sore that heals and then reopens

- A white, waxy, or scar-like lesion

These tumours are most commonly found on areas of the skin that receive frequent sun exposure, such as the face, neck, ears, scalp, and arms. If you notice any persistent changes in your skin, it is important to have them checked by a healthcare professional.

What causes basal cell carcinoma in the skin?

Basal cell carcinoma is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors that damage the DNA in skin cells. Key risk factors include:

- Ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure: People with fair skin that burns quickly and those exposed to intense, intermittent UV radiation (like sunburns) are at higher risk of developing basal cell carcinoma.

- Age and gender: Older adults and men are more likely to develop basal cell carcinoma.

- Radiation therapy: Radiation treatments, especially during childhood, are strongly associated with basal cell carcinoma.

- Chronic arsenic exposure: Long-term exposure to arsenic, often through contaminated water, can increase the risk of basal cell carcinoma.

- Genetic conditions: Certain genetic syndromes, such as Gorlin syndrome (also called naevoid BCC syndrome), xeroderma pigmentosum, Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome, and Rombo syndrome, significantly increase the risk of developing basal cell carcinoma.

- Melanin-related genes: Variations in genes like MC1R, ASIP, and TYR, which regulate melanin production, can also increase basal cell carcinoma risk.

These factors contribute to DNA damage in basal cells, leading to cancer development over time.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma begins with a careful skin examination by a doctor. If a suspicious lesion is identified, the next step is usually a biopsy. During a biopsy, a small piece of tissue is removed from the lesion so a pathologist can examine it under a microscope.

Types of basal cell carcinoma

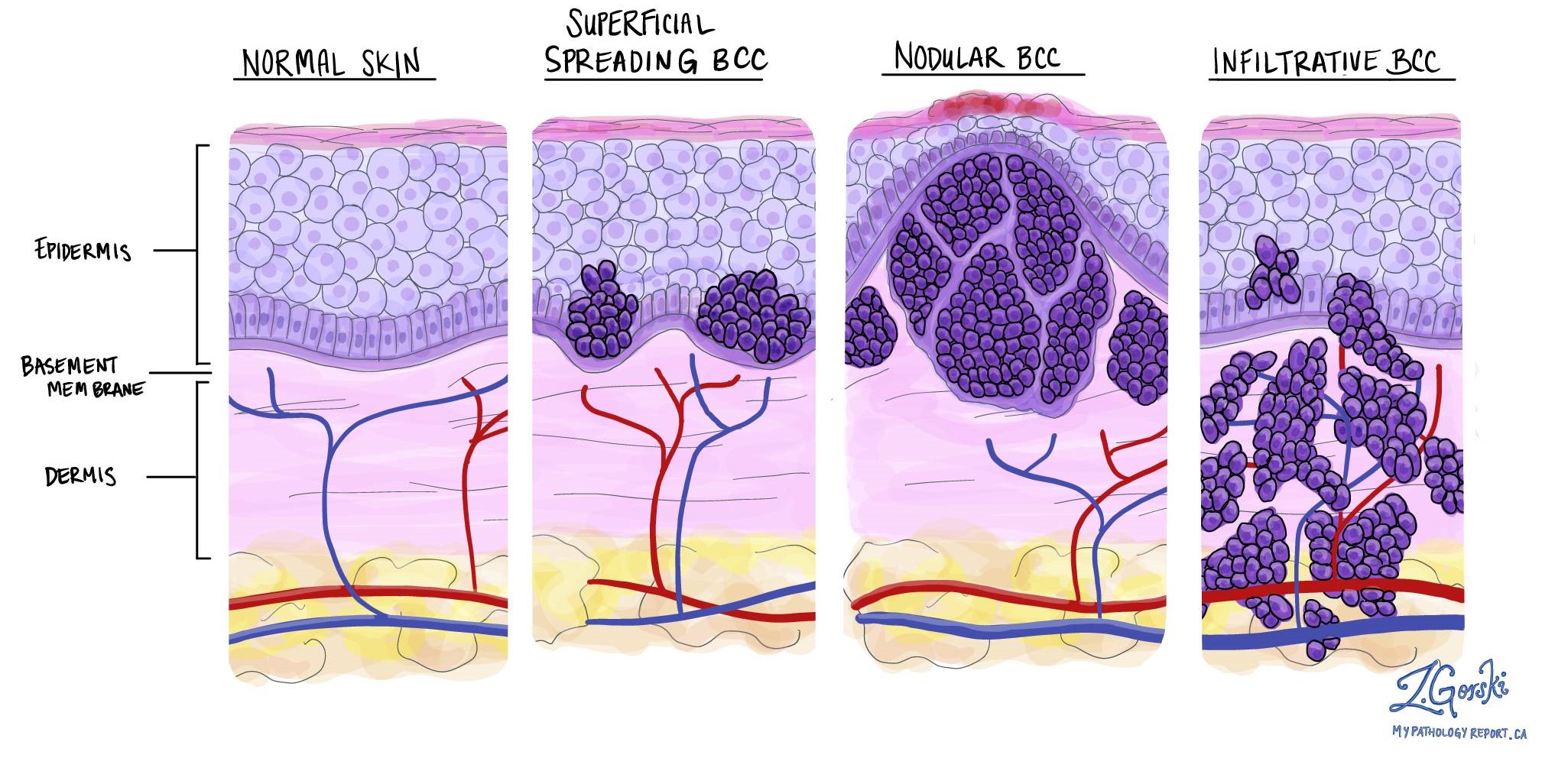

Pathologists divide basal cell carcinoma into histologic types based on how the cancer cells stick together and the shapes they form as the tumour grows. The type can only be determined after a pathologist examines the tumour under a microscope. A tumour may be made up of one or multiple histologic types.

Infiltrating type

Infiltrating is a high-risk type of basal cell carcinoma. It is called “infiltrating” because the tumour comprises small groups of cancer cells that grow deeply into a part of the skin called the dermis. This deep pattern of invasion makes it difficult for surgeons to remove the tumour fully. As a result, this type is more likely to regrow after surgery than low-risk basal cell carcinoma types.

Micronodular type

Micronodular is a high-risk type of basal cell carcinoma. It is called “micronodular” because the tumour is made up of very small (“micro”) groups of cancer cells called nodules. The nodules of cancer cells typically spread deeply into a part of the skin called the dermis. This deep pattern of invasion makes it difficult for surgeons to remove the tumour fully. As a result, the micronodular type is more likely to regrow after surgery compared to low-risk types of basal cell carcinoma.

Nodular type

Nodular is the most common type of basal cell carcinoma. It is called “nodular” because the tumour cells connect to form large groups called “nodules” in a layer of the skin called the dermis. It is considered a low-risk type of basal cell carcinoma.

Pigmented type

Pigmented is a low-risk type of basal cell carcinoma. This type of cancer is called “pigmented” because a pigment called melanin is found throughout the tumour. The melanin pigment gives the tumour its dark colour.

Sclerosing type

Sclerosing (morphoeic) is a high-risk type of basal cell carcinoma. This type of cancer is called “sclerosing” because the tumour comprises very small groups of cancer cells surrounded by dense connective tissue called collagen, which pathologists describe as “sclerotic”. The groups of cancer cells typically spread deeply into a part of the skin called the dermis. This deep pattern of invasion makes it difficult for surgeons to remove the tumour entirely. As a result, the sclerosing type is more likely to regrow after surgery compared to low-risk types of basal cell carcinoma.

Superficial type

Superficial is a relatively common type of basal cell carcinoma. It is called “superficial” because most of the tumour is found at the junction of the epidermis and the dermis, near the surface of the skin. It is considered a low-risk type of basal cell carcinoma.

Tumour thickness

Basal cell carcinoma of the skin starts in a thin layer of tissue on the skin’s surface called the epidermis. Tumour thickness measures how far the tumour cells have spread from the top of the epidermis into the layers of tissue below (the dermis and subcutaneous tissue). Tumour thickness is similar but different from the depth of invasion, which measures how far the tumour cells have spread from the bottom of the epidermis to the deepest level of invasion.

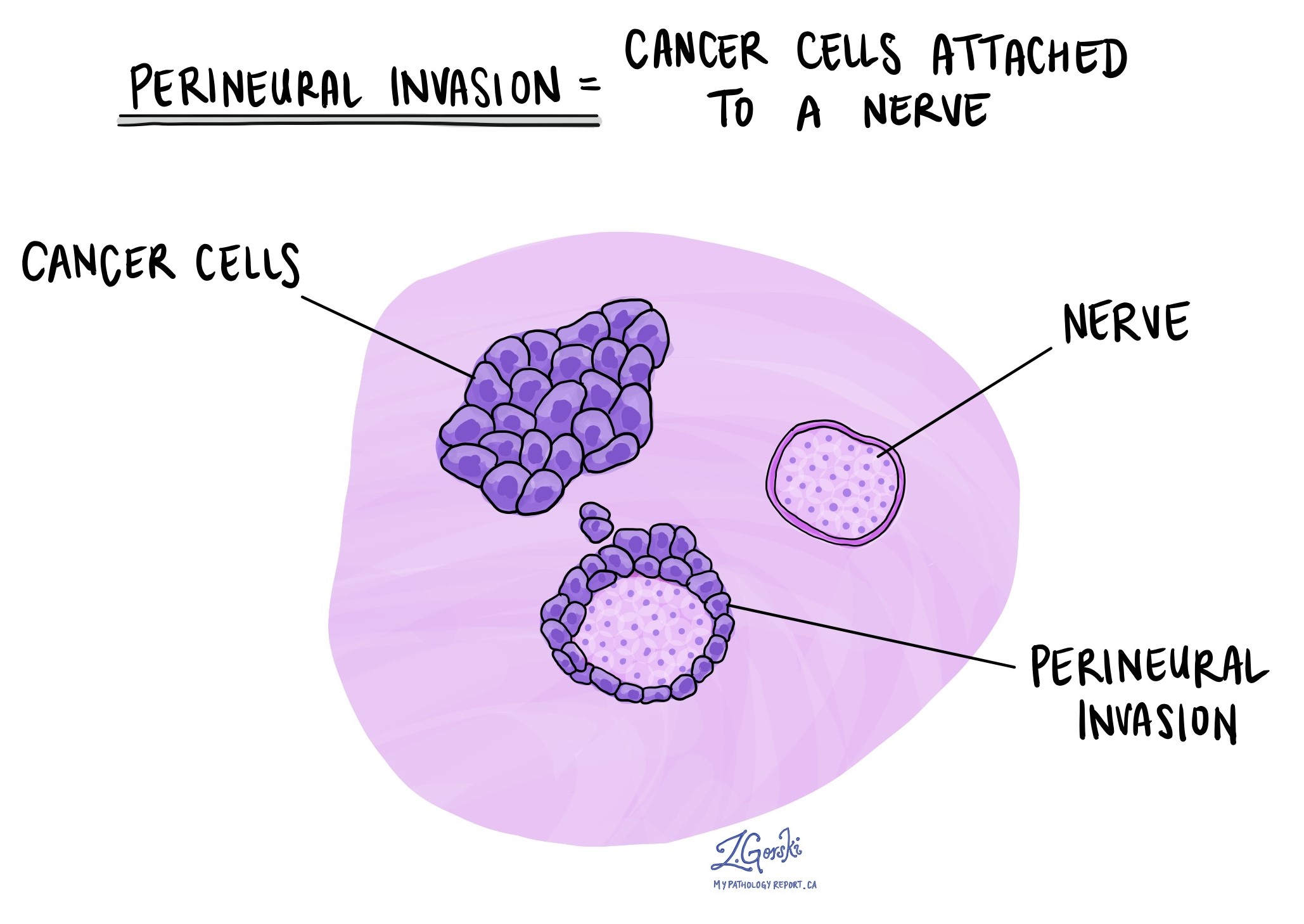

Perineural invasion

Pathologists use the term “perineural invasion” to describe a situation where cancer cells attach to or invade a nerve. “Intraneural invasion” is a related term that specifically refers to cancer cells inside a nerve. Nerves, resembling long wires, consist of groups of cells known as neurons. These nerves, present throughout the body, transmit information such as temperature, pressure, and pain between the body and the brain. Perineural invasion is important because it allows cancer cells to travel along the nerve into nearby organs and tissues, raising the risk of the tumour recurring after surgery.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion occurs when cancer cells invade a blood vessel or lymphatic channel. Blood vessels, thin tubes that carry blood throughout the body, contrast with lymphatic channels, which carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. These lymphatic channels connect to small immune organs known as lymph nodes, scattered throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because it spreads cancer cells to other body parts, including lymph nodes or the lungs, via the blood or lymphatic vessels.

Margins

In pathology, a margin is the edge of tissue removed during tumour surgery. The margin status in a pathology report is important as it indicates whether the entire tumour was removed or if some was left behind. This information helps determine the need for further treatment.

Pathologists typically assess margins following a surgical procedure like an excision or resection, which removes the entire tumour. Margins aren’t usually evaluated after a biopsy, which removes only part of the tumour. The number of margins reported and their size—how much normal tissue is between the tumour and the cut edge—vary based on the tissue type and tumour location.

Pathologists examine margins to check if tumour cells are at the tissue’s cut edge. A positive margin, where tumour cells are found, suggests that some cancer may remain in the body. In contrast, a negative margin, with no tumour cells at the edge, suggests the tumour was fully removed. Some reports also measure the distance between the nearest tumour cells and the margin, even if all margins are negative. The micronodular and infiltrating types of basal cell carcinoma are associated with a higher risk of a positive margin because there is no clear boundary between the edge of the tumour and the adjacent normal tissue.

What does completely excised mean?

Completely excised means that the surgical procedure successfully removed the entire tumour. Pathologists determine if a tumour is entirely excised by examining the margins of the tissue (see above for more information about margins).

What does incompletely excised mean?

Incompletely excised means that the surgical procedure removed only part of the tumour. Pathologists describe a tumour as incompletely excised when tumour cells are seen at the margin or cut edge of the tissue (see above for more information about margins).

It is normal for a tumour to be incompletely excised after a minor procedure such as a biopsy because these procedures are usually not performed to remove the entire tumour. However, larger operations such as excisions and resections are usually performed to remove the entire tumour. If a tumour is incompletely excised, your doctor may recommend another procedure to remove the rest of the tumour.

What is the prognosis for a person diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma?

The prognosis for basal cell carcinoma is generally very good, especially when diagnosed and treated early. These cancers grow slowly and rarely spread to other body parts (metastasize). However, if left untreated, they can grow larger and invade nearby tissues, potentially causing significant damage, especially if located near sensitive structures like the eyes, ears, or nose.

Most basal cell carcinomas are successfully treated with minor surgery or other localized treatments, such as freezing (cryotherapy) or topical medications. Once treated, the risk of recurrence at the same site is low, but having one basal cell carcinoma increases the risk of developing another in the future. Regular skin checks and sun protection prevent new tumours from growing and ensure early detection. If you have been diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma, your doctor can help you develop a plan for treatment and long-term skin care.