by Emily Goebel, MD FRCPC

June 7, 2023

What is mucinous carcinoma of the ovary?

Mucinous carcinoma is a type of ovarian cancer. It develops from the tissue on the inside of the ovary. The tumour is usually made up of many small spaces. Pathologists call these spaces cysts. The walls of the cysts can be thin or thick and more solid areas may be found inside some of the cysts. The cysts are often filled with a thick fluid called mucin.

How do pathologists make this diagnosis?

For most women, the diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma is only made when the entire tumour has been surgically removed and sent to a pathologist for examination. The fallopian tube and uterus may be removed at the same time.

Your surgeon may request an intraoperative or frozen section consultation from your pathologist. The diagnosis made by your pathologist during the intraoperative consultation can change the type of surgery performed or the treatment offered after the surgery is completed.

What does mucinous carcinoma of the ovary look like under the microscope?

When the tumour is examined under the microscope, the tissue on the inside of the cysts and the solid areas are made up of an abnormal type of epithelium that forms glands and produces a thick, gelatinous fluid called mucin. The mucin fills the inside of the tumour.

Your pathologist will carefully examine the tumour under the microscope for features that will help determine your prognosis. All mucinous carcinomas start in the epithelium and the movement of cancer cells into the stroma is called invasion. In some cases, this cancer develops from a pre-existing mucinous borderline tumour. If your pathologist also sees a mucinous borderline tumour, it will be described in your report.

Some cancers, such as those from the appendix, may look very similar to mucinous carcinoma from the ovary. For that reason, your pathologist may perform a test called immunohistochemistry to help confirm the diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma and rule out the possibility that cancer from another organ, such as the appendix, may have spread to the ovary.

Mucinous carcinomas of the ovary may be positive or reactive for immunohistochemical markers such as PAX8, CK7, CK20 and CDX2 and negative or non-reactive for SATB2, which you may see included in your pathology report.

Pattern of growth

The pattern of growth describes the way the cancer cells spread into the normal surrounding stroma. The pattern of growth can only be determined after the tissue sample has been examined under the microscope by a pathologist. The pattern of growth is important because infiltrative growth is associated with a worse prognosis when compared to expansile growth.

- Infiltrative growth – In this pattern, single cancer cells or irregularly shaped glands are seen spreading into the stroma.

- Expansile growth – In this pattern, the cancer cells are pushing into the stroma as a large group.

Histologic grade

Pathologists use the word grade to describe the difference between the cancer cells and normal mucinous epithelium. Because in other parts of the body, normal mucinous epithelium forms glands, mucinous carcinoma is divided into 3 grades based on how much of the tumour is made up of glands:

- Well differentiated – The cancer cells mostly form glands, with only a small percentage of the cancer cells growing in a non-glandular or solid pattern.

- Moderately differentiated – Some glands are still seen but a significant amount of non-glandular or solid pattern is seen.

- Poorly differentiated – The cancer cells are growing mostly in a non-glandular or solid pattern with very few glands.

Intact or ruptured tumour

All ovarian tumours are examined to see if there are any holes or tears in the outer (capsular) surface of the ovary. The capsular surface is described as intact if no holes or tears are identified. The capsular surface is described as ruptured if it contains any large holes or tears. If the ovary or tumour is received in multiple pieces, it may not be possible for your pathologist to tell if the capsular surface has ruptured or not.

This information is important because a capsular surface that ruptures inside the body may spill cancer cells into the abdominal cavity. A ruptured capsule is associated with a worse prognosis and is used to determine the tumour (T) stage.

Ovarian surface involvement

Your pathologist will carefully examine the tissue under the microscope to see if there are any cancer cells on the surface of the ovary. Cancer cells on the surface of the ovary increase the risk that the tumour will spread to other organs in the pelvis or abdomen. It is also used to determine the tumour stage.

Other organs or tissues involved

Small samples of tissue are commonly removed in a procedure called a biopsy to see if cancer cells have spread to the pelvis or abdomen. These biopsies which are often called omentum or peritoneum are sent for pathological examination along with the tumour.

Other organs (such as the bladder, small intestine, or large intestine) are not typically removed and sent for pathological examination unless they are directly attached to the tumour. In these cases, your pathologist will examine each organ under the microscope to see if there are any cancer cells attached to those organs. Cancer cells in other organs are used to determine the tumour stage.

The appendix

If you have been diagnosed with mucinous carcinoma or if your doctor suspects you may have mucinous carcinoma, your appendix might also be removed and sent for pathological examination. In these cases, your pathologist will examine the appendix for any cancer cells. Cancers of the appendix can look very similar to mucinous carcinoma of the ovary. Cancers that start in the appendix can spread from the appendix to the ovary.

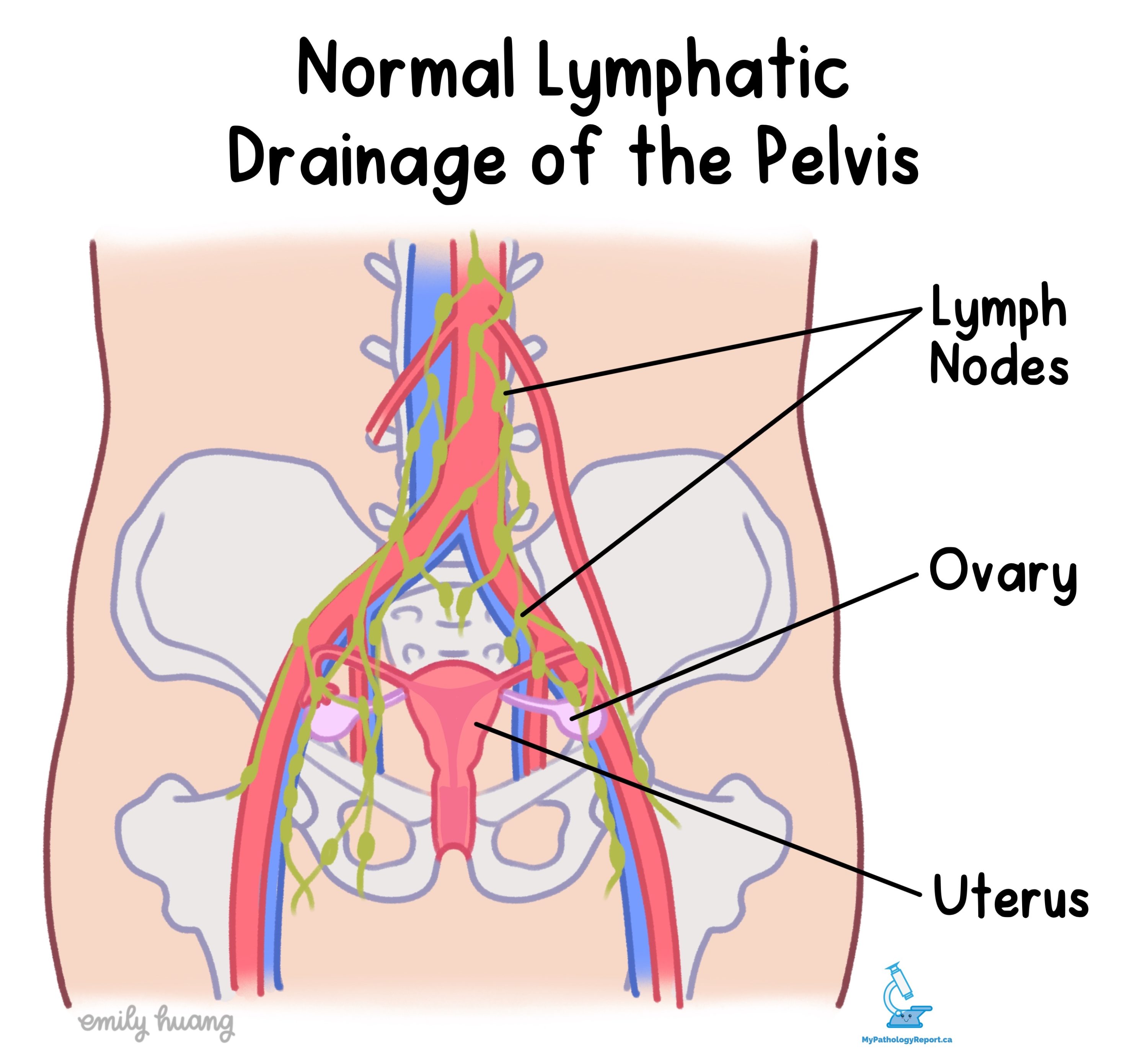

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs located throughout the body. Cancer cells can travel from the tumour to a lymph node through lymphatic channels located in and around the tumour. The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to a lymph node is called metastasis.

Your pathologist will carefully examine all lymph nodes for cancer cells. Lymph nodes that contain cancer cells are often called positive while those that do not contain any cancer cells are called negative. Most reports include the total number of lymph nodes examined and the number, if any, that contain cancer cells.

If cancer cells are found in a lymph node, the size of the area involved by cancer will be measured and described in your report.

- Isolated tumour cells – The area inside the lymph node with cancer cells is less than 0.2 millimetres in size.

- Micrometastases – The area inside the lymph node with cancer cells is more than 0.2 millimetres but less than 2 millimetres in size.

- Macrometastases – The area inside the lymph node with cancer cells is more than 2 millimetres in size.

Cancer cells found in a lymph node are associated with a higher risk that the cancer cells will be found in other lymph nodes or in a distant organ such as the lungs. The number of lymph nodes with cancer cells is also used to determine the nodal stage (see Pathologic stage below).