by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Zuzanna Gorski MD FRCPC

August 9, 2025

Pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disease of the skin and mucous membranes. In this condition, the body’s immune system mistakenly produces antibodies that attack healthy tissue. These antibodies target specific proteins that normally help anchor the top layer of skin (the epidermis) to the deeper layer (the dermis). When these proteins are damaged, the connection between the two layers weakens, and fluid can collect in the space, forming blisters.

Unlike some other blistering diseases, pemphigoid causes tense blisters that do not break easily. The condition most often affects older adults, but it can occur in children and infants. It is not contagious.

What are the symptoms of pemphigoid?

Pemphigoid usually starts with a prodrome phase, where patients notice intense itching and areas of skin that look like hives or eczema. Over time, the condition enters the bullous stage, when large, tense blisters filled with clear or blood-tinged fluid appear. The skin around the blisters may be red or inflamed.

The blisters most often form on the inner thighs, groin, lower abdomen, or the flexor surfaces of the arms and legs. In most people, the mouth and other mucous membranes are not affected, although about 10–30% may develop sores inside the mouth.

What causes pemphigoid?

Pemphigoid is an autoimmune disease, meaning it is caused by the immune system attacking the body’s own cells. In pemphigoid, the immune system produces IgG antibodies that target two proteins—BP180 (also called BPAG2) and BP230 (also called BPAG1)—which are part of structures called hemidesmosomes. These structures help anchor the epidermis to the dermis.

When antibodies damage these proteins, the skin layers separate, creating a blister.

Certain medications—such as some blood pressure drugs, antibiotics, and immune checkpoint inhibitors used in cancer treatment—can trigger pemphigoid in some people. In children, rare cases have been reported after viral illness or vaccinations.

How is this diagnosis made?

Doctors suspect pemphigoid based on symptoms and the appearance of the skin. The diagnosis is confirmed by:

-

Skin biopsy for routine microscopic examination to see where the blister forms and which immune cells are present.

-

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) to detect antibodies bound in the skin.

-

Blood tests to measure antibodies against BP180 and BP230.

What does pemphigoid look like under the microscope?

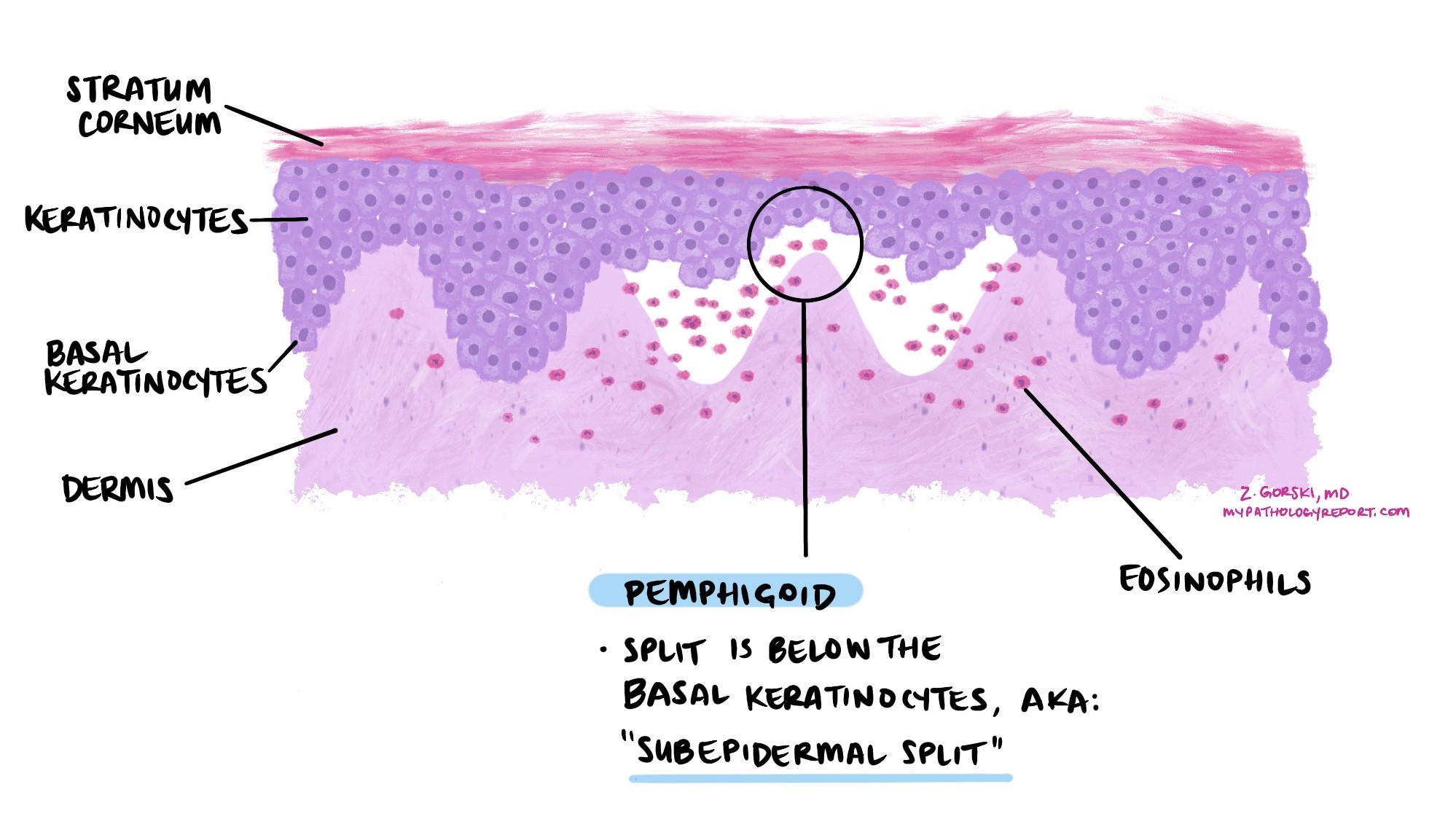

Under the microscope, pemphigoid shows a subepidermal blister, meaning the split occurs between the epidermis and the dermis. The blister cavity and surrounding skin often contain large numbers of eosinophils, a type of white blood cell involved in allergic and immune reactions. In early stages, eosinophils can be seen spreading into the epidermis, a change called eosinophilic spongiosis.

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF)

Direct immunofluorescence is a special test pathologists use to detect antibodies and complement proteins that are bound to the skin. For this test, a small piece of skin near, but not directly in, a blister is taken and treated with fluorescent dyes that bind to antibodies.

In pemphigoid, DIF usually shows a linear band of complement protein C3, often with IgG, along the basement membrane zone (the junction between epidermis and dermis). This pattern is sometimes described as n-serrated under high magnification.

A related test, salt-split skin analysis, can help distinguish pemphigoid from other blistering diseases. In pemphigoid, the antibodies bind to the “roof” of the blister created in this test.

What is the difference between pemphigoid and pemphigus?

Pemphigoid and pemphigus are both autoimmune diseases that cause blisters on the skin and mucous membranes, but they differ in where the blisters form, the type of immune attack, and the appearance of the blisters.

In pemphigoid, the immune system targets proteins that anchor the epidermis (top skin layer) to the dermis (deeper skin layer). This causes a split below the epidermis (subepidermal blister). Because the deeper layer of skin is intact, these blisters are tense and firm and do not break easily.

In pemphigus, the immune system attacks proteins that connect squamous cells to each other within the epidermis. This causes the cells to separate (a process called acantholysis) and creates a split inside the epidermis (intraepidermal blister). Without the support of deeper skin layers, these blisters are flaccid and fragile, breaking easily to form painful erosions.

The differences in blister location also mean the diseases can behave differently. Pemphigoid tends to cause more stable blisters that heal slowly, while pemphigus often causes widespread raw areas because the blisters break so easily. Both require treatment to control the immune response, but the exact approach can vary.

Prognosis

With proper treatment, most people with pemphigoid can control their symptoms and prevent new blisters from forming. However, the disease can relapse, especially during the first year of treatment. Relapse risk is higher in people with more severe disease, certain neurological conditions, or persistently high antibody levels.

Treatment

Treatment focuses on reducing inflammation, stopping blister formation, and suppressing the abnormal immune response. Common treatments include:

-

Topical or oral corticosteroids to quickly control inflammation.

-

Steroid-sparing medications such as mycophenolate mofetil or methotrexate to reduce long-term steroid use.

-

Tetracycline antibiotics (sometimes with nicotinamide) for their anti-inflammatory effects.

-

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or rituximab for severe or treatment-resistant disease.

Good skin care and infection prevention are important because blisters and erosions can allow bacteria to enter the skin.

Questions to ask your doctor

- Which treatments do you recommend for me, and why?

-

How will we monitor whether the treatment is working?

-

What side effects should I watch for with these medications?

-

How can I reduce my risk of relapse?