by Ashley Flaman MD and Bibianna Purgina MD FRCPC

February 12, 2024

A pheochromocytoma is a type of neuroendocrine tumour that originates from the chromaffin cells of the adrenal gland, which is located on top of the kidneys. These cells are responsible for producing and releasing hormones like adrenaline and noradrenaline, which are crucial for your body’s stress response.

Most (about 75-90%) of pheochromocytomas are non-cancerous tumours. However, some may behave more like cancer by spreading to other parts of the body. Unfortunately, there are no findings that pathologists can see under the microscope that can separate non-cancerous from cancerous tumours with 100% certainty. Therefore, if you are diagnosed with a pheochromocytoma, you will be asked to follow up regularly with your doctor to ensure the tumour has not spread.

What causes a pheochromocytoma?

The development of these tumours is often linked to genetic mutations, which can be either inherited or acquired spontaneously. Several genes have been identified that, when mutated (altered), increase the risk of developing pheochromocytomas. These include genes involved in the cellular oxygen sensing pathway (such as VHL), genes that are part of the succinate dehydrogenase complex (such as SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD), and others related to neuroendocrine tumour development (like RET and NF1). While a portion of pheochromocytomas occur as part of hereditary syndromes, many cases appear sporadically without a clear familial link, suggesting that environmental factors or random genetic mutations may also play a role.

What are the symptoms of pheochromocytoma?

Hormones produced by the tumour cells can cause symptoms such as a racing heart, headaches, sweating, and high blood pressure. However, some pheochromocytomas do not cause any symptoms and are only found when imaging such as a CT scan or MRI is performed for an unrelated reason.

What is the difference between a pheochromocytoma and a paraganglioma?

Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma are both neuroendocrine tumours that look similar when examined under the microscope. However, unlike pheochromocytomas which only start in the adrenal gland, paragangliomas can start in any location where autonomic ganglion cells are normally found. Paragangliomas are commonly found in the head, neck, or in the back along the spine. Pheochromocytoma is considered an “intra-adrenal paraganglioma”.

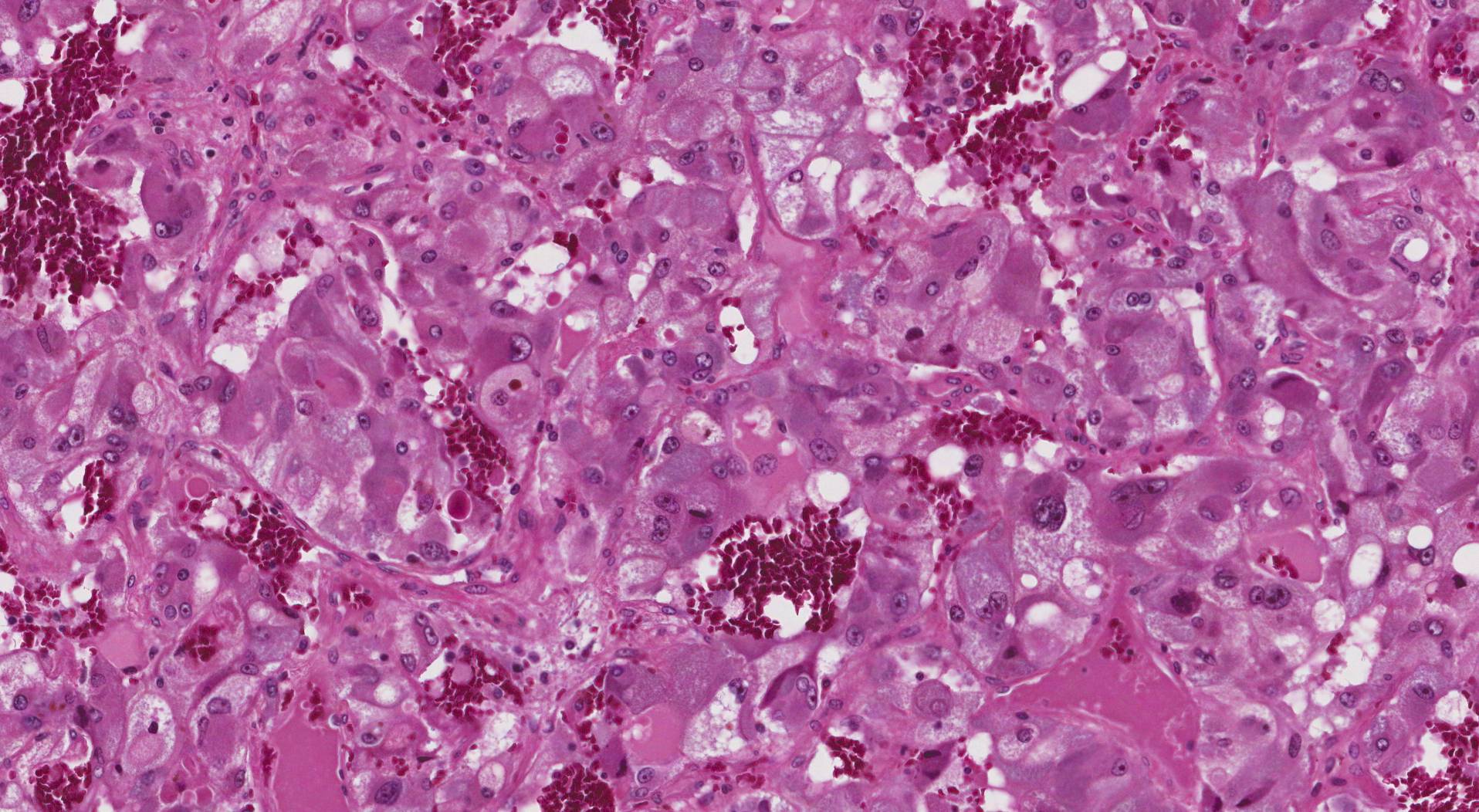

Microscopic features of this tumour

When examined under the microscope, most pheochromocytomas are made up of large pink or purple cells. The tumour cells are usually arranged in round groups that pathologists describe as “zellballen”, which translates from German to mean “cell balls”. The groups of cells are surrounded by long thin sustentacular cells. The tumour is typically surrounded by a thin layer of tissue called a tumour capsule. When a test called immunohistochemistry (IHC) is performed, the tumour cells are positive for synaptophysin and chromogranin while the sustentacular cells are positive for S100.

SDHB

SDHB (Succinate Dehydrogenase Complex, subunit B) is a protein involved in cellular energy production. The production of SDHB is lost in patients who have inherited a gene that puts them at greater risk for developing pheochromocytomas and other neuroendocrine tumours. Pathologists performed a test called immunohistochemistry (IHC) for SDHB to identify patients who may have inherited a genetic syndrome.

Possible SDHB IHC results:

- Retained expression (normal): The tumour is unlikely to be caused by an inherited genetic syndrome.

- Loss of expression (abnormal): The tumour may be associated with an inherited genetic syndrome. Genetic counselling and further genetic tests are advised.

Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal Gland Scaled Score (PASS)

Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal Gland Scaled Score (PASS) is a tool that doctors use to predict the behaviour of a pheochromocytoma. A score of 3 or less means that the tumour is likely to behave in a non-cancerous manner and is cured by surgery alone. In contrast, a score of 4 or more means the tumour is more likely to behave like cancer and spread to other parts of the body.

To determine the PASS score, your pathologist will look for specific microscopic features. Each feature is given a set number of points which are added up to give the total PASS score.

- Invasion of periadrenal adipose tissue – The tumour cells have spread outside the adrenal gland and into the fat that surrounds it = 2 points.

- > 3 mitoses for every 10 high power fields – There are more than 3 dividing cells in a pathologist’s 10 fields of view at 400X magnification (high power fields) = 2 points.

- Atypical mitoses – The dividing cells look abnormal when examined under the microscope. This leads to new cells which are unable to function normally = 2 points.

- Necrosis – The tumour cells are dying = 2 points.

- Cellular spindling – The tumour cells are longer than they are round = 2 points.

- Cellular monotony – All of the cells look the same as each other = 2 points.

- Large nests or diffuse growth – The cells are growing in large groups instead of forming small cell balls (zellballen) = 2 points.

- High cellularity – There are more tumour cells and they are more closely packed together than normally expected for a pheochromocytoma = 2 points.

- Marked nuclear pleomorphism – All of the cells look very different from each other = 1 point.

- Capsular invasion – The tumour cells have spread past the tumour capsule into the tissue outside of the adrenal gland = 1 point.

- Vascular invasion – The tumour cells are found inside blood vessels = 1 point.

- Hyperchromatic tumour cells – The part of the cell that holds the genetic material, the nucleus, is much darker than normal = 1 point.