by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

April 28, 2023

What is squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity?

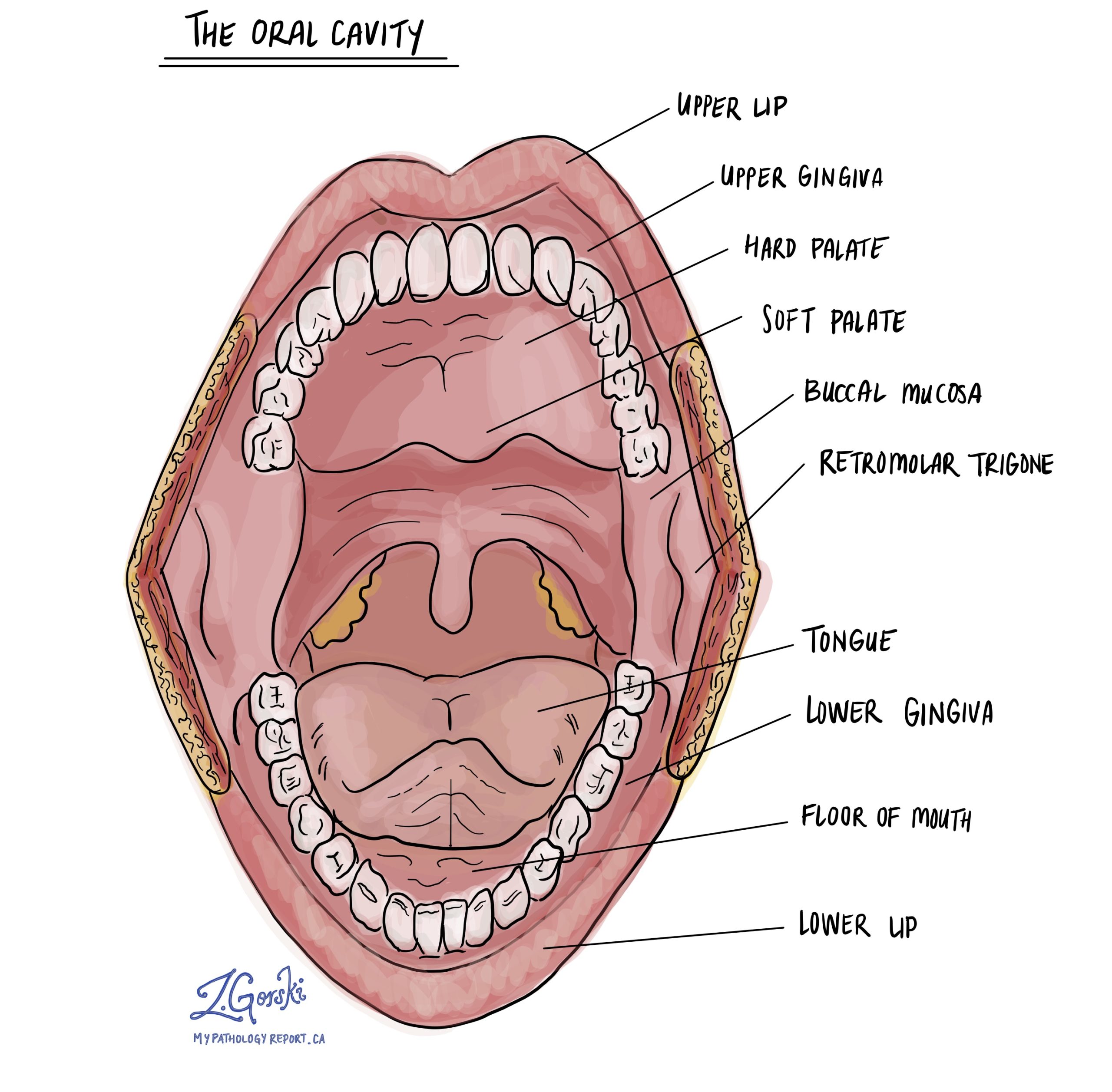

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common type of cancer in the oral cavity. The oral cavity includes the lips, tongue, floor of the mouth, gingiva (gums), buccal mucosa (inner cheeks), and palate (roof of the mouth). Squamous cell carcinoma often develops from a pre-cancerous disease called squamous dysplasia which may be present for many years before turning into squamous cell carcinoma.

What causes squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity?

Smoking, high levels of alcohol consumption, chronic inflammatory conditions such as lichen planus, and immunosuppression all increase the risk of developing both squamous cell carcinoma and squamous dysplasia. Rare cases are caused by infection with high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV).

How is the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity made?

The diagnosis is usually made after a small tissue sample is removed in a procedure called a biopsy. The tissue sample is then sent to a pathologist who examines it under the microscope. Most patients will then undergo a second procedure to remove the entire tumour. That tissue is also sent to a pathologist for examination under the microscope.

What does it mean if squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity is described as well, moderately, or poorly differentiated?

Pathologists divide squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity into three grades – well, moderately, and poorly differentiated – based on how much the tumour cells look like normal squamous cells when examined under the microscope. The grade is important because higher-grade tumours (moderately and poorly differentiated tumours) behave in a more aggressive manner and are more likely to spread to other parts of the body.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity is graded as follows:

- Well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity – A well differentiated tumour (also known as grade 1) is made up of tumour cells that look almost the same as normal squamous cells.

- Moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity – A moderately differentiated tumour (also known as grade 2) is made up of tumour cells that clearly look different from normal squamous cells, however, they can still be recognized as squamous cells.

- Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity – A poorly differentiated tumour (also known as grade 3) is made up of tumour cells that look very little like normal squamous cells. These cells can look so abnormal that your pathologist may need to order an additional test such as immunohistochemistry to confirm the diagnosis.

What does it mean if squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity is described as keratinizing?

Keratinizing is a term pathologists use to describe cells that look pink when examined under the microscope because the cytoplasm (body) of the cell contains large amounts of a specialized protein called keratin. Like normal squamous cells, the tumour cells in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity produce large amounts of keratin and will be described as keratinizing.

What does the depth of invasion mean?

All squamous cell carcinomas in the oral cavity start from a thin layer of tissue called the epithelium that covers the entire inside surface of the oral cavity. Below the epithelium are other types of tissue that are often described together as stroma or submucosa. Pathologists use the word invasion to describe the movement of tumour cells from the epithelium into the tissue below and the depth of invasion is a measurement of the farthest the tumour cells have travelled.

The depth of invasion is important because tumours with a depth of invasion greater than 0.5 centimetres are more likely to spread to lymph nodes in the neck. The depth of invasion is also used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (see Pathologic stage below).

What is lymphovascular invasion and why is it important?

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells were seen inside a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. The lymphatic vessels connect with small immune organs called lymph nodes that are found throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because cancer cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other parts of the body such as lymph nodes or the lungs. If lymphovascular invasion is seen, it will be included in your report.

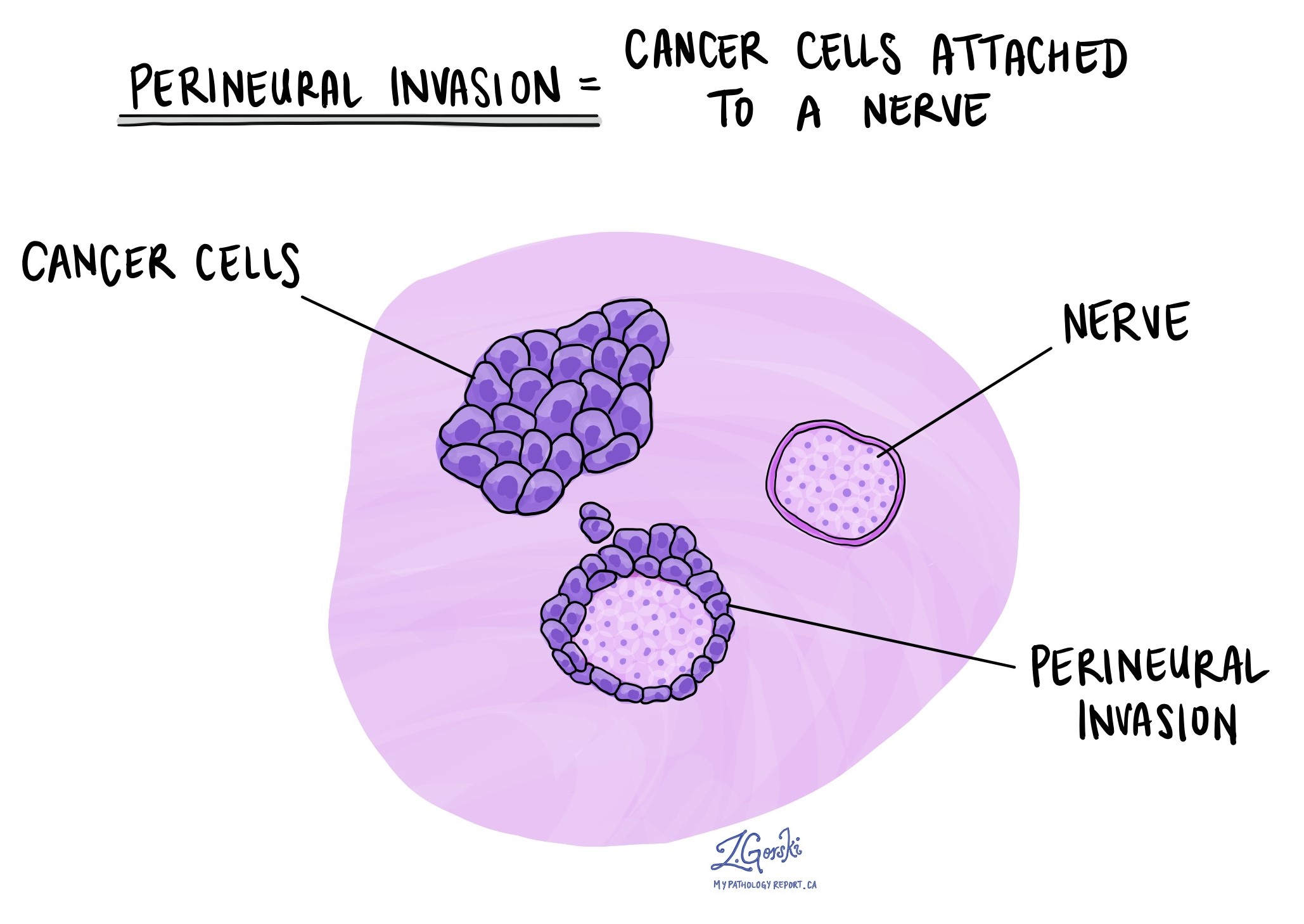

What is perineural invasion and why is it important?

Perineural invasion is a term pathologists use to describe cancer cells attached to or inside a nerve. A similar term, intraneural invasion, is used to describe cancer cells inside a nerve. Nerves are like long wires made up of groups of cells called neurons. Nerves are found all over the body and they are responsible for sending information (such as temperature, pressure, and pain) between your body and your brain. Perineural invasion is important because the cancer cells can use the nerve to spread into surrounding organs and tissues. This increases the risk that the tumour will regrow after surgery. If perineural invasion is seen, it will be included in your report.

Were lymph nodes examined and did any contain cancer cells?

Lymph nodes are small immune organs found throughout the body. Cancer cells can spread from a tumour to lymph nodes through small vessels called lymphatics. Lymph nodes are not always removed at the same time as the tumour. However, when lymph nodes are removed, they will be examined under a microscope and the results will be described in your report.

Cancer cells typically spread first to lymph nodes close to the tumour although lymph nodes far away from the tumour can also be involved. For this reason, the first lymph nodes removed are usually close to the tumour. Lymph nodes further away from the tumour are only typically removed if they are enlarged and there is a high clinical suspicion that there may be cancer cells in the lymph node. Most reports will include the total number of lymph nodes examined, where in the body the lymph nodes were found, and the number (if any) that contain cancer cells. If cancer cells were seen in a lymph node, the size of the largest group of cancer cells (often described as “focus” or “deposit”) will also be included.

Why is the examination of lymph nodes important?

The examination of lymph nodes is important for two reasons. First, this information is used to determine the pathologic nodal stage (pN). Second, finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the risk that cancer cells will be found in other parts of the body in the future. As a result, your doctor will use this information when deciding if additional treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy is required.

What does it mean if a lymph node is described as positive?

Pathologists often use the term “positive” to describe a lymph node that contains cancer cells. For example, a lymph node that contains cancer cells may be called “positive for malignancy” or “positive for metastatic carcinoma”.

What does it mean if a lymph node is described as negative?

Pathologists often use the term “negative” to describe a lymph node that does not contain any cancer cells. For example, a lymph node that does not contain cancer cells may be called “negative for malignancy” or “negative for metastatic carcinoma”.

What does extranodal extension mean?

All lymph nodes are surrounded by a thin layer of tissue called a capsule. Extranodal extension means that cancer cells within the lymph node have broken through the capsule and have spread into the tissue outside of the lymph node. Extranodal extension is important because it increases the risk that the tumour will regrow in the same location after surgery. For some types of cancer, extranodal extension is also a reason to consider additional treatment such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

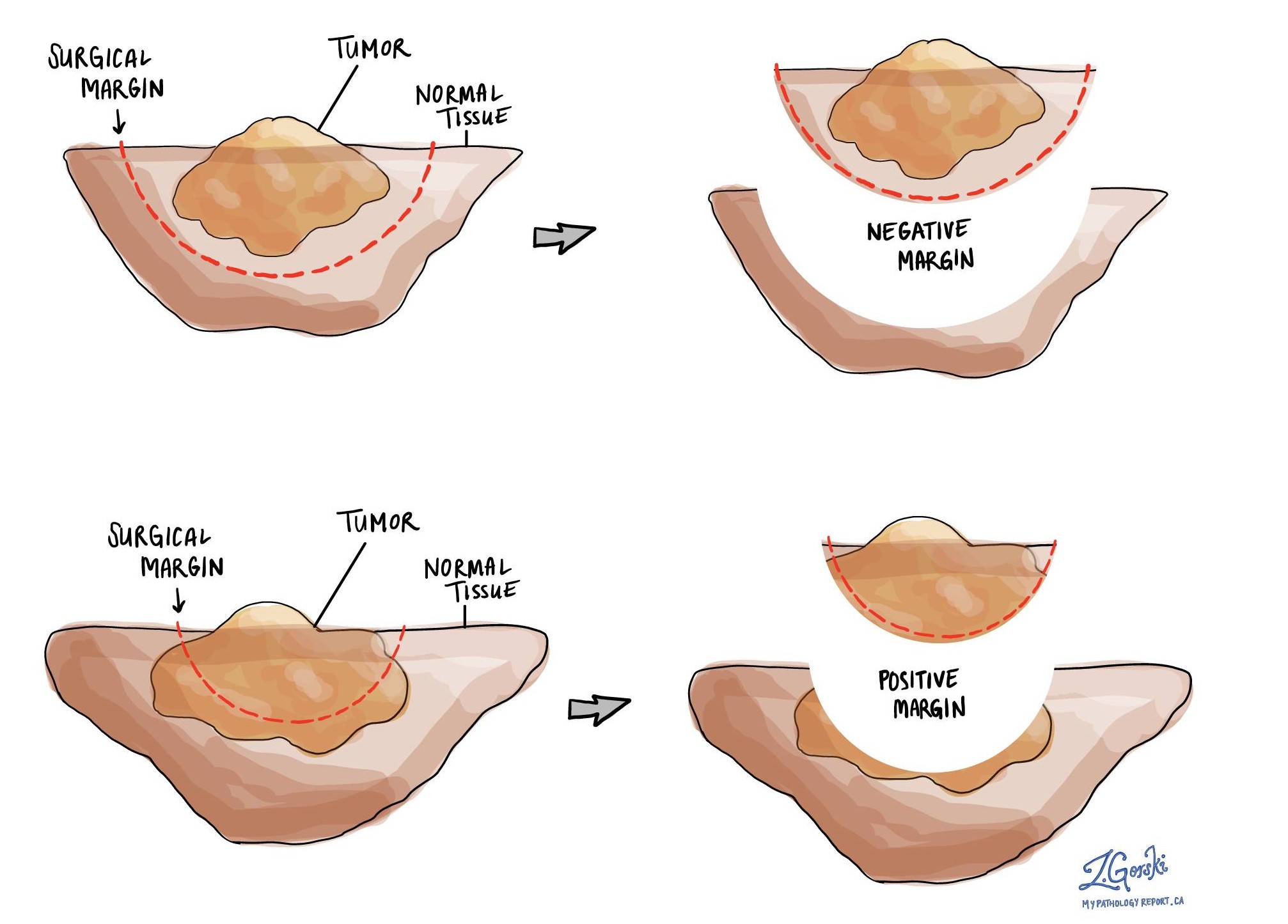

What is a margin?

In pathology, a margin is the edge of a tissue that is cut when removing a tumour from the body. The margins described in a pathology report are very important because they tell you if the entire tumour was removed or if some of the tumour was left behind. The margin status will determine what (if any) additional treatment you may require.

Most pathology reports only describe margins after a surgical procedure called an excision or resection has been performed for the purpose of removing the entire tumour. For this reason, margins are not usually described after a procedure called a biopsy is performed for the purpose of removing only part of the tumour.

Pathologists carefully examine the margins to look for tumour cells at the cut edge of the tissue. If tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, the margin will be described as positive. If no tumour cells are seen at the cut edge of the tissue, a margin will be described as negative. Even if all of the margins are negative, some pathology reports will also provide a measurement of the closest tumour cells to the cut edge of the tissue.

A positive (or very close) margin is important because it means that tumour cells may have been left behind in your body when the tumour was surgically removed. For this reason, patients who have a positive margin may be offered another surgery to remove the rest of the tumour or radiation therapy to the area of the body with the positive margin.

How do pathologists determine the pathologic stage (pTNM) for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity?

The pathologic stage for squamous cell carcinoma is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system originally created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT) for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity

Your pathologist will look for three features in order to determine the tumour stage:

- The size of the tumour.

- The depth of invasion.

- The presence of cancer cells in nearby tissues.

Based on these features, squamous cell carcinoma is given a tumour stage between 1 and 4:

- Tis – The cancer cells are only seen in the epithelium at the surface of the tissue. They do not invade the stroma.

- T1 – The tumour is less than or equal to 2 centimetres in size AND the depth of invasion is no greater than 0.5 centimetres.

- T2 – The tumour is greater than 2 centimetres but less than 4 centimetres OR the depth of invasion is greater than 0.5 centimetres but less than or equal to 1 centimetre.

- T3 – The tumour is greater than 4 centimetres OR the depth of invasion is greater than 1 centimetre.

- T4 – The tumour invades tissues outside of the oral cavity such as the bones of the jaw or the sinuses.

Nodal stage (pN) for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity

Your pathologist will look for four features in order to determine the nodal stage:

- The size of the tumour deposit.

- The number of lymph nodes that contain cancer cells.

- The presence of extranodal extension.

- Whether the lymph nodes with cancer cells are on the same or opposite side of the neck as the main tumour (laterality).

Based on these features, squamous cell carcinoma is given a nodal stage between 0 and 3. The N2 and N3 stages are divided into smaller groups with letters (a, b, or c) after the number. If no lymph nodes are submitted for pathological examination, the N-stage cannot be determined and the N stage is listed as X.

Metastatic stage (pM) for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity

Squamous cell carcinoma is given a metastatic stage of 0 or 1 based on the presence of cancer cells at a distant site in the body (for example the lungs). The metastatic stage can only be assigned if tissue from a distant site is sent for pathological examination. Because this tissue is rarely present, the metastatic stage cannot be determined and is listed as MX.