by Ipshita Kak MD FRCPC

December 20, 2023

Well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour (NET) of the colon and rectum is a type of cancer made up of neuroendocrine cells. The tumour can develop anywhere along the length of the colon and rectum although it is most commonly found in the rectum. Pathologists divide these tumours into three grades (G1 through G3) with higher-grade tumours being associated with more aggressive behaviour and worse overall prognosis.

What is the difference between a functional and non-functional neuroendocrine tumour?

Well differentiated neuroendocrine tumours can be divided into functional and non-functional tumours based on the types of symptoms they produce. Functional tumours produce proteins that can result in specific symptoms. These symptoms or detecting specific proteins in the blood or urine can help doctors make the correct diagnosis. Non-functional tumours do not produce proteins, and as a result, may go undetected for many years.

Some patients with functional well differentiated neuroendocrine tumours present with a very specific set of symptoms that doctors call “carcinoid syndrome”. The presence of this syndrome suggests that the tumour has spread to the liver. The tumours can also be detected by imaging and endoscopy.

What does a well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour look like under the microscope?

When examined under the microscope, a well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour is made up of specialized neuroendocrine cells that can show a variety of growth patterns including nested, trabecular, pseudo-glandular, pseudo-acinar, and solid. The cells throughout the tumour tend to be very similar looking which pathologists describe as monomorphic or monotonous. The genetic material or chromatin inside the nucleus of the cell often appears as small dots which pathologists describe as “salt and pepper”.

What other tests are performed to confirm the diagnosis?

A special test called immunohistochemistry may be performed to confirm the diagnosis. This test allows pathologists to better understand cells based on the specific proteins they produce. This test allows pathologists better to understand both the function and origin of the cell.

The cells in a well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour commonly produce three proteins: CD56, synaptophysin and chromogranin. By performing immunohistochemistry, your pathologist can ‘see’ these proteins inside the cell. Most cancers produce all three proteins, but some may produce two or even just one of the three. Cells that produce a protein will be called positive or reactive. Those that do not produce the protein are called negative or non-reactive.

What does grade mean and why is it important?

Well differentiated neuroendocrine tumours in the colon and rectum are divided into three grades. The grade is important because higher-grade tumours (grades 2 and 3) are more likely to spread to other parts of the body. The grade can only be determined after the tumour is examined under the microscope by your pathologist.

Pathologists determine the grade by measuring the number of tumour cells that are in the process of dividing to create new tumour cells. These cells are called mitotic figures and they are undergoing a process called mitosis. The mitotic rate is the number of dividing cells seen when the tumour is examined at high magnification through the microscope (pathologists call this a ‘high powered field’ or ‘HPF’).

Your pathologist may also do a test called immunohistochemistry for Ki-67 to highlight cells that can divide. The Ki-67 index (or proliferative index) is the percentage of tumour cells that produce Ki-67. The proliferative index for well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours can range from 1% to over 20%.

Your pathologist will use the mitotic rate and/or the Ki-67 index to determine the grade as follows:

- Grade 1 (G1) – A grade 1 well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour has a mitotic rate of less than 2 or a Ki-67 index of less than 3%.

- Grade 2 (G2) – A grade 2 well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour has a mitotic rate between 2 and 20 or a Ki-67 index of between 3% and 20%.

- Grade 3 (G3) – A grade 3 well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour has a mitotic rate of greater than 20 or a Ki-67 index of greater than 20%.

What does invasion mean and why is it important?

Pathologists use the word invasion to describe the spread of tumour cells from the inside of the colon into the surrounding tissues. Well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour starts from neuroendocrine cells normally found within the glands on the inside surface of the colon and rectum. The glands are part of a thin layer of tissue called the mucosa. The layers of tissue below the mucosa include the submucosa, muscularis propria, subserosal adipose tissue, and serosa. As the tumour grows the cells can spread into these layers. Eventually, the tumour cells can break through the outside surface of the colon and spread directly into nearby organs and tissues.

The level of invasion is the deepest point of invasion and it can only be measured after the tumour is examined under the microscope by a pathologist. The level of invasion is important because tumours that invade deeper into the wall of the colon are more likely to spread to other parts of the body. The level of invasion is also used to determine the pathologic tumour stage (pT).

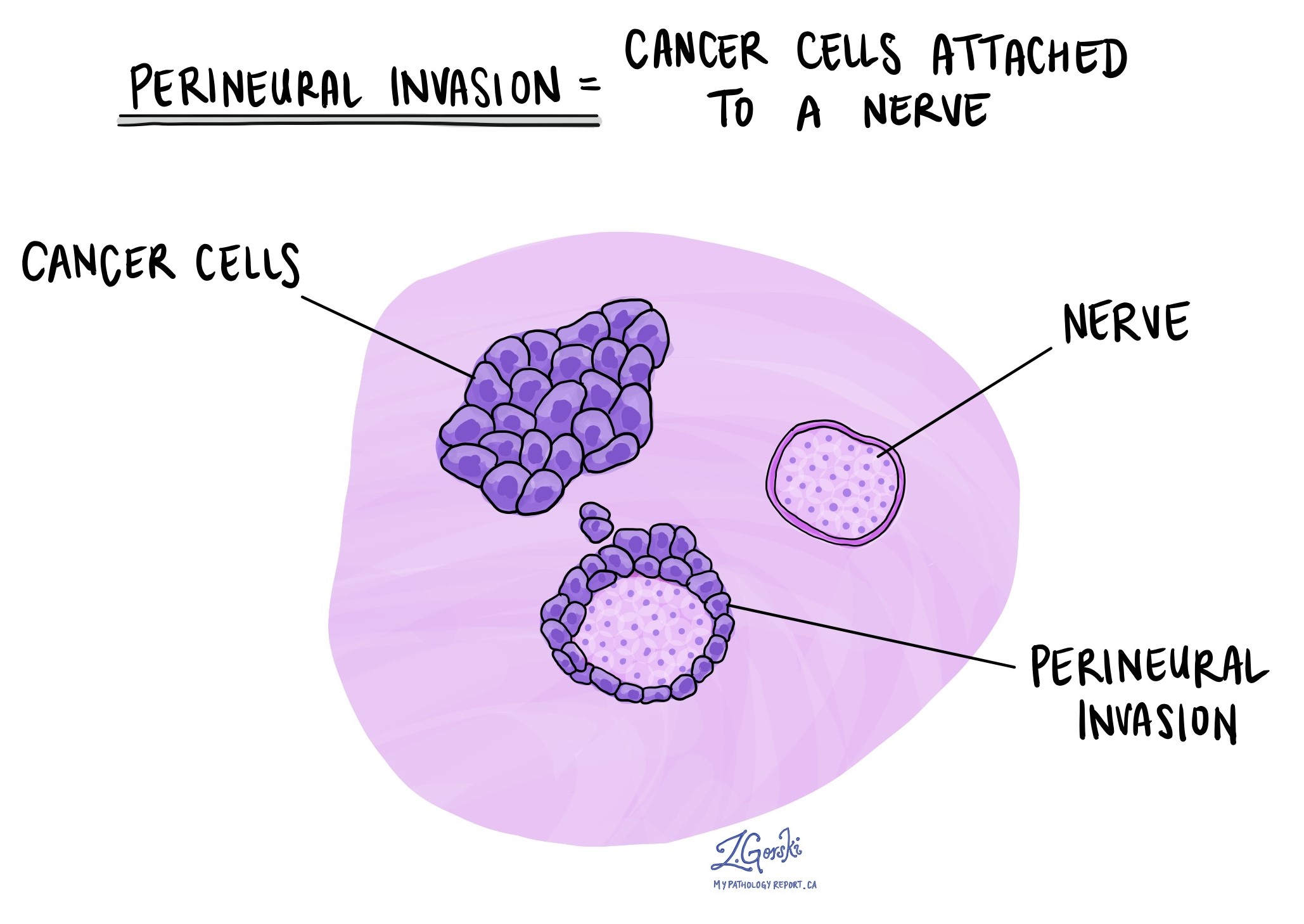

What does perineural invasion mean and why is it important?

Perineural invasion is a term pathologists use to describe cancer cells attached to or inside a nerve. A similar term, intraneural invasion, is used to describe cancer cells inside a nerve. Nerves are like long wires made up of groups of cells called neurons. Nerves are found all over the body and they are responsible for sending information (such as temperature, pressure, and pain) between your body and your brain. Perineural invasion is important because the cancer cells can use the nerve to spread into surrounding organs and tissues. This increases the risk that the tumour will regrow after surgery. If perineural invasion is seen, it will be included in your report.

What is lymphovascular invasion and why is it important?

Lymphovascular invasion means that cancer cells were seen inside a blood vessel or lymphatic vessel. Blood vessels are long thin tubes that carry blood around the body. Lymphatic vessels are similar to small blood vessels except that they carry a fluid called lymph instead of blood. The lymphatic vessels connect with small immune organs called lymph nodes that are found throughout the body. Lymphovascular invasion is important because cancer cells can use blood vessels or lymphatic vessels to spread to other parts of the body such as lymph nodes or the lungs. If lymphovascular invasion is seen, it will be included in your report.

What is a margin and why are margins important?

A margin is any tissue cut by the surgeon to remove the tumour from your body. The types of margins described in your report will depend on the organ involved and the type of surgery performed. Margins will only be described in your report after the entire tumour has been removed.

A negative margin means that no tumour cells were seen at any of the cut edges of the tissue. A margin is called positive when there are tumour cells at the very edge of the cut tissue. A positive margin is associated with a higher risk that the tumour will recur in the same site after treatment.

What are lymph nodes and why are they important?

Lymph nodes are small immune organs located throughout the body. Cancer cells can travel from the tumour to a lymph node through lymphatic channels located in and around the tumour (see Lymphovascular invasion above). The movement of cancer cells from the tumour to a lymph node is called metastasis.

Your pathologist will carefully examine each lymph node for cancer cells. Lymph nodes that contain cancer cells are often called positive while those that do not contain any cancer cells are called negative. Most reports include the total number of lymph nodes examined and the number, if any, that contain cancer cells. The examination of lymph nodes is used to determine the nodal stage (pN). Finding cancer cells in a lymph node increases the nodal stage and is associated with a worse prognosis.

What information is used to determine the pathologic stage?

The pathologic stage for well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour is based on the TNM staging system, an internationally recognized system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). This system uses information about the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastatic disease (M) to determine the complete pathologic stage (pTNM). Your pathologist will examine the tissue submitted and give each part a number. In general, a higher number means a more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.

Tumour stage (pT)

The tumour stage (pT) for well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour in the colon and rectum is based on the size of the tumour and how far the tumour cells have travelled into the wall of the colon or rectum or the surrounding tissues.

- T1 – The tumour is located entirely within the mucosa and is 2 cm or less in size.

- T2 – The tumour is greater than 2 cm in size or it has invaded the muscularis propria.

- T3 – The tumour has gone through the entire muscular wall of the colon or rectum and is into the subserosal tissue (just under the outer surface of the colon).

- T4 – The tumour is on the outer surface of the colon or has gone into surrounding organs.

Nodal stage (pN)

The nodal stage (pN) for well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour in the colon and rectum is based on the presence or absence of tumour cells in a lymph node.

- N0 – No tumour cells are seen in any of the lymph nodes examined.

- N1 – Tumour cells are seen in at least one lymph node.

- NX – No lymph nodes were sent for pathologic examination.

Metastatic stage (pM)

The metastatic stage (ispM) for well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour in the colon and rectum is based on the presence of tumour cells at a distant site in the body (for example the liver). The metastatic stage can only be assigned if tissue from a distant site is submitted for pathological examination. Because this tissue is rarely present, the metastatic stage cannot be determined and is listed as MX.