By Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC and Matt Cecchini MD PhD FRCPC

November 27, 2025

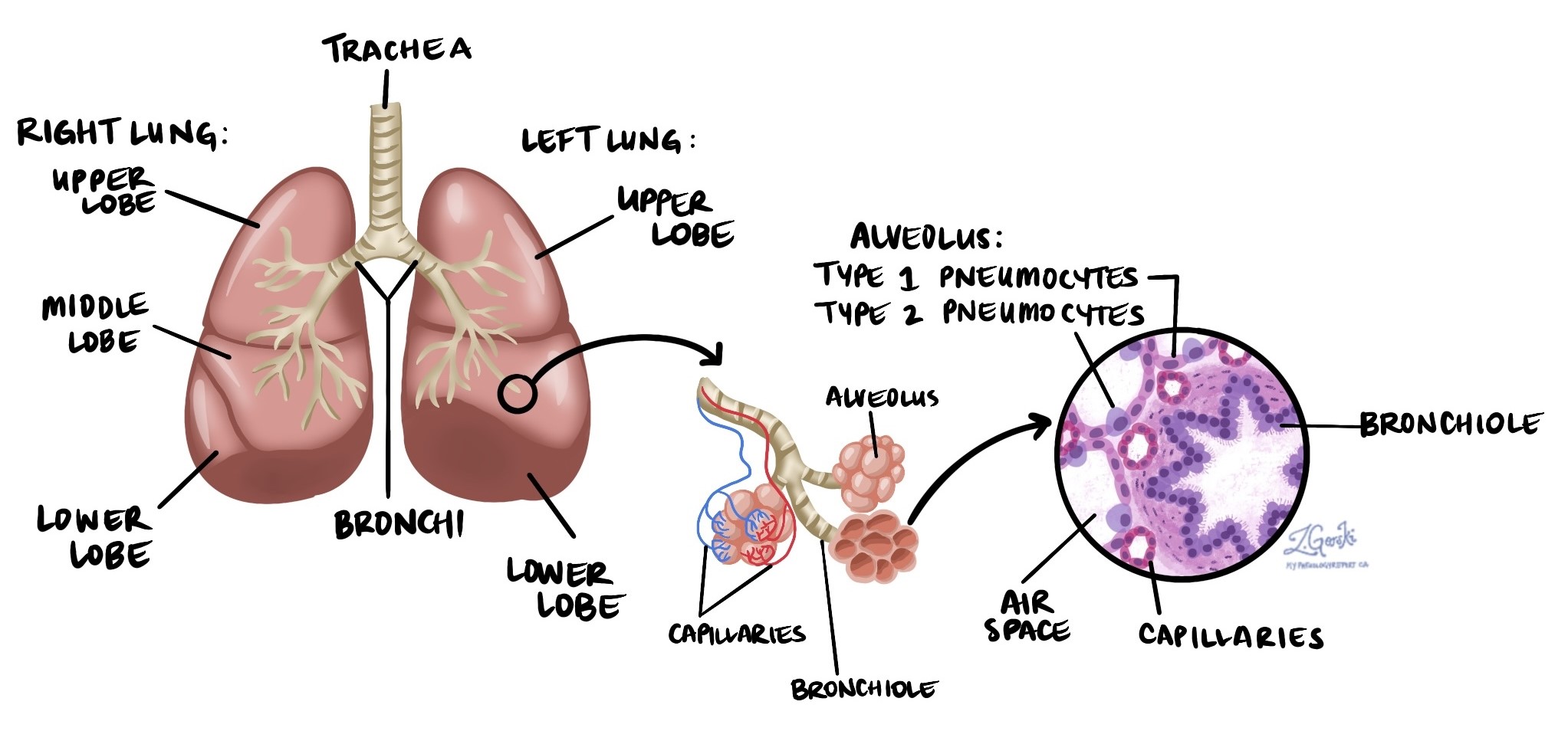

Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of lung cancer, accounting for about 40% of all lung cancer cases in North America. It belongs to the group of cancers known as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Adenocarcinoma begins in pneumocytes, the specialized cells that line the tiny air sacs of the lungs called alveoli. Alveoli are where oxygen enters the bloodstream, and carbon dioxide is removed.

Because adenocarcinoma often starts near the outer edges of the lung, it may be detected early when imaging tests—such as X-rays or CT scans—show a small nodule or mass.

What causes adenocarcinoma in the lung?

The leading cause of adenocarcinoma in the lung is tobacco smoking. This includes cigarettes, cigars, and pipes. However, adenocarcinoma can also occur in people who have never smoked.

Other causes and risk factors include:

-

Radon exposure.

-

Occupational exposures, such as asbestos, silica, or diesel exhaust.

-

Outdoor air pollution.

These factors can damage lung cells and increase the risk of cancer over time.

What are the symptoms of adenocarcinoma in the lung?

The symptoms of lung adenocarcinoma vary. Some people have no symptoms, especially in the early stages. When symptoms appear, they may include:

-

A persistent or worsening cough.

-

Coughing up blood.

-

Chest pain.

-

Shortness of breath.

-

Fatigue or unintentional weight loss.

If the cancer spreads to other parts of the body, symptoms depend on the location. For example, spread to bones can cause pain or even a pathologic fracture, which is a broken bone caused by cancer weakening the bone tissue.

What conditions are associated with adenocarcinoma of the lung?

Adenocarcinoma of the lung may arise from precancerous conditions such as:

-

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) is a condition where the lining cells of the alveoli look abnormal but are not cancerous.

-

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) is a non-invasive cancer limited to the inner surface of the alveoli and smaller than 3 cm.

AIS can progress to invasive adenocarcinoma when the tumor grows beyond 3 cm or when cancer cells invade the supporting tissue beneath the alveolar lining.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of adenocarcinoma starts when imaging tests show a suspicious area in the lung. To confirm the diagnosis, a biopsy is performed to remove a small tissue sample. Biopsies may be obtained by needle biopsy, bronchoscopy, endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS), or fine needle aspiration (FNA). The tissue sample is then examined under the microscope by a pathologist, a doctor who specializes in diagnosing diseases by studying tissue.

If cancer is confirmed, surgery may be recommended to remove the tumor. The type of surgery depends on the tumor’s size and location. Smaller tumors near the outer surface may be removed by wedge resection, while larger or more central tumors may require a lobectomy or even a pneumonectomy.

After removal, the pathologist examines the entire tumor. Important features include:

-

The pattern of growth (histologic type).

-

Whether the cancer has spread into the surrounding lung tissue.

-

Whether spread through air spaces (STAS) is present.

-

Whether tumor cells have entered blood vessels or lymphatic channels.

-

Whether the tumor has grown into the pleura.

-

Whether the surgical margins are clear.

-

Whether lymph nodes contain cancer cells.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunohistochemistry is a special test that uses antibodies linked to dyes to detect specific proteins within cells. These proteins act as “markers” that help the pathologist confirm the type of cancer and determine where it started.

Adenocarcinoma of the lung typically shows the following results:

-

TTF-1: Positive.

-

p40: Negative.

-

CK5: Negative.

-

Chromogranin: Negative.

-

Synaptophysin: Negative.

This staining pattern supports the diagnosis and helps rule out other types of lung cancer such as squamous cell carcinoma or neuroendocrine tumors.

Histologic types of adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma of the lung is divided into histologic types based on how the cancer cells grow. A tumor may show one or several patterns.

Lepidic type

Cancer cells grow along the inner surface of the alveoli. If completely lepidic and less than 3 cm, the tumor is classified as AIS.

Acinar type

Tumor cells form round, gland-like structures.

Solid type

Tumor cells grow in dense sheets with little open space. This type is more aggressive.

Papillary type

Tumor cells form finger-like projections called papillae.

Micropapillary type

Tumor cells form tiny clusters that resemble tufts. This is a highly aggressive pattern.

Tumor grade

For adenocarcinoma of the lung tumor grade describes how aggressive the cancer appears under the microscope. The grade is based on two microscopic features:

-

The predominant histologic pattern.

-

The worst (most aggressive) pattern seen anywhere in the tumor.

Tumours with predominantly lepidic growth and minimal solid or micropapillary features are well differentiated, meaning they grow more slowly and have a better prognosis. Tumors with acinar or papillary growth and small amounts of aggressive patterns are moderately differentiated. Tumors that contain large amounts of solid or micropapillary growth are poorly differentiated, meaning they behave more aggressively, grow faster, and are more likely to spread.

Tumor grade is one of the most important predictors of prognosis, especially in early-stage disease.

Spread through air spaces (STAS)

STAS means that cancer cells are found floating within the air spaces of the lung beyond the edge of the main tumor. These cells are separate from the primary mass and can travel through the small air channels of the lung.

The presence of STAS is associated with a higher risk of recurrence, especially after limited surgery such as wedge resection. Because of this, STAS is included in the pathology report and helps guide treatment decisions.

Multiple tumors

It is possible to find more than one tumor in the lungs. In these situations, each tumor is examined separately. Sometimes, multiple tumors represent spread from a single original tumor, especially when they look identical under the microscope. When smaller secondary growths appear in the same lung as the primary tumor, they are often called nodules, which are small, rounded lesions that may represent metastatic spread within the lung.

In other cases, the tumors may have formed independently, especially if they show different histologic patterns or features. For example, one tumor may be adenocarcinoma while another is squamous cell carcinoma. When tumors arise separately, they are considered separate primary cancers and not metastatic disease. Distinguishing between these two possibilities is important because it affects staging, treatment, and prognosis.

Pleural invasion

The pleura is a thin membrane with two layers:

-

The visceral pleura covers the surface of the lungs.

-

The parietal pleura, which lines the inside of the chest cavity.

Pleural invasion means cancer cells have grown into one or both of these layers. Tumors that invade only the visceral pleura are considered locally more advanced than tumors limited to the lung tissue itself. Tumors that invade the parietal pleura—the outer layer attached to the chest wall—are considered even more advanced, because the cancer has grown beyond the lung and reached the chest cavity lining. Pleural invasion increases the T stage and is associated with a higher risk of spread and recurrence.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) occurs when cancer cells enter blood vessels or lymphatic vessels in or near the tumor. These vessels act as pathways for cancer to spread to other parts of the body, including lymph nodes, bones, liver, or brain. When lymphovascular invasion is present, the risk of metastasis is higher, and additional treatment may be recommended.

Margins

Margins are the edges of tissue removed during surgery. The pathologist examines all margins to determine whether the tumor was removed entirely. A negative margin means no cancer cells are seen at the cut edge. A positive margin means cancer is present at the edge, raising concern that some cancer remains. Margin status helps doctors decide whether further surgery or radiation is needed.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small immune organs that filter lymph fluid. Lung adenocarcinoma commonly spreads to lymph nodes in the lung and central chest. During surgery, lymph nodes from specific anatomical regions (called lymph node stations) may be removed and examined.

The pathology report will state the number of lymph nodes examined, where they were located, and whether they contain cancer. This information helps determine the nodal stage and plays a major role in selecting treatment.

Pathologic stage (pTNM)

Lung adenocarcinoma is staged using the TNM system:

-

The T stage describes the tumor size and whether it has invaded nearby structures.

-

The N stage describes whether lymph nodes contain cancer.

-

The M stage describes whether the cancer has spread to distant organs such as the brain, bones, or liver.

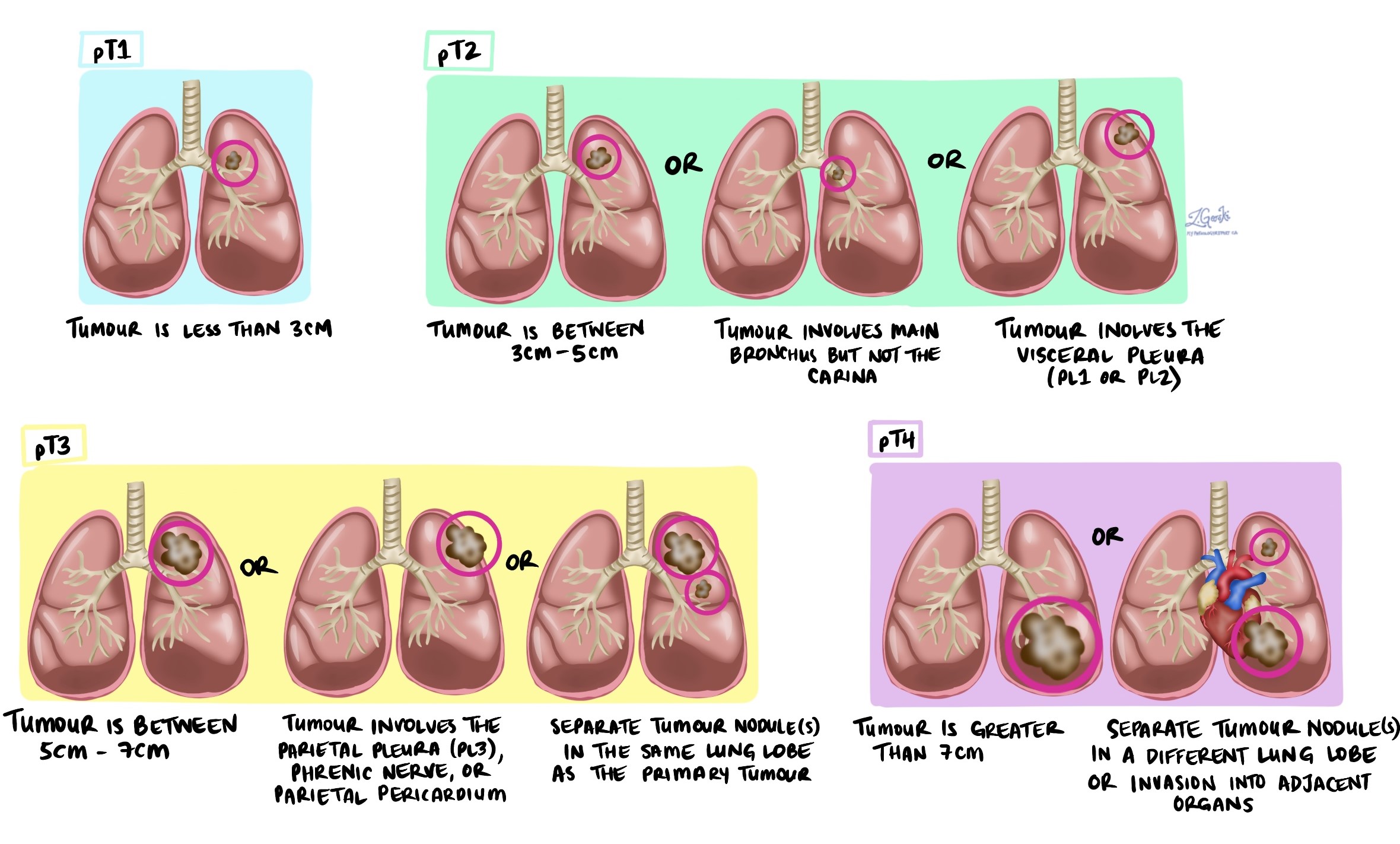

Tumour stage (pT)

-

T1: Tumour is 3 cm or smaller.

-

T2: Tumour is larger than 3 cm but not larger than 5 cm, or it has invaded the visceral pleura or central airways.

-

T3: Tumour is larger than 5 cm but not larger than 7 cm or has grown into nearby tissues.

-

T4: Tumour is larger than 7 cm or has invaded nearby organs such as the heart or esophagus.

Nodal stage (pN)

-

NX: Lymph nodes were not examined.

-

N0: No cancer cells in lymph nodes.

-

N1: Cancer cells in lymph nodes inside the lung or near airways (stations 10–14).

-

N2: Cancer cells in lymph nodes in the central chest near the airways (stations 7–9).

-

N3: Cancer cells in lymph nodes on the opposite side of the chest or in the lower neck (stations 1–6).

Higher stages have a higher risk of spread and recurrence and often require more intensive treatment.

Biomarkers for adenocarcinoma of the lung

Biomarkers are measurable changes in cancer cells, often involving specific genes or proteins. These changes help doctors understand how the tumour behaves and which treatments may work best. In lung adenocarcinoma, biomarkers are especially important because many tumours harbour genetic alterations that can be targeted with therapies that block the abnormal signals that help the cancer grow. Biomarker testing is now a standard part of diagnosis and guides many treatment decisions.

What types of biomarkers are tested in lung adenocarcinoma?

Most biomarker testing for lung adenocarcinoma focuses on genetic mutations and gene rearrangements found in the tumour’s DNA. These changes are detected using specialized laboratory techniques such as PCR (a test that amplifies small pieces of DNA), next-generation sequencing (NGS; a test that examines many genes at once), and FISH (a test that uses fluorescent probes to detect gene rearrangements). These tests are performed on biopsy tissue, or the tumour removed during surgery, and play an essential role in determining which treatments may be most effective.

EGFR

EGFR is a gene that encodes a receptor that controls cell growth. When EGFR harbours specific mutations, the receptor becomes overactive, driving tumour growth. EGFR mutations are prevalent in people who have never smoked, in women, and in individuals of East Asian ancestry. These mutations are important because tumours with EGFR alterations often respond very well to EGFR-targeted therapies, which block the abnormal growth signal and can shrink the tumour or slow its progression.

Pathologists test for EGFR mutations by examining the tumour’s DNA using PCR or next-generation sequencing to detect specific genetic changes.

Your pathology report will describe the tumour as EGFR-positive if a mutation is detected and EGFR-negative if no mutation is found.

ALK

ALK is a gene that can fuse with another gene, creating an abnormal fusion protein that promotes tumour growth. These ALK fusions are more common in younger patients and people who have never smoked. ALK rearrangements are important because tumours with this change often respond exceptionally well to ALK-targeted therapies, which block the abnormal fusion protein.

ALK testing is performed using immunohistochemistry, which highlights ALK protein in tumour cells, FISH, which detects ALK gene rearrangements, or next-generation sequencing, which analyzes the ALK gene directly.

Tumours are described as ALK-positive when a rearrangement is present and ALK-negative when no rearrangement is found.

ROS1

ROS1 is a gene that can undergo rearrangement, forming a fusion protein that stimulates tumour growth. Although less common than EGFR or ALK alterations, ROS1 fusions are important because they respond very well to ROS1-targeted therapies, which block the abnormal protein and help control the cancer.

ROS1 testing can be performed by immunohistochemistry, FISH, or next-generation sequencing to detect a ROS1 gene fusion.

Your tumour will be described as ROS1-positive if a fusion is found and ROS1-negative if it is not.

BRAF

BRAF is a gene involved in regulating cell growth. Specific mutations, such as the BRAF V600E mutation, can cause tumour cells to grow more rapidly. These mutations are important because tumours with BRAF alterations may respond to BRAF-targeted therapies, which block the abnormal signalling pathway.

Testing is performed by analyzing tumour DNA using PCR or next-generation sequencing to identify specific BRAF mutations.

Your tumour will be described as BRAF-positive if a mutation is present and BRAF-negative if no mutation is detected.

MET

MET is a gene that helps control normal cell growth. A specific abnormality, MET exon 14 skipping, causes the MET protein to remain active longer than usual, allowing tumour cells to grow unchecked. This biomarker is important because tumours with MET exon 14 skipping often respond to MET-targeted therapies.

MET testing is usually performed using next-generation sequencing to detect MET exon 14 skipping or other MET mutations.

Your tumour will be classified as MET-positive if a MET mutation is detected, and as MET-negative if no mutation is found.

RET

RET is a gene that can fuse with another gene, creating an abnormal protein that drives tumour growth. RET fusions are important because tumours with this change often respond exceptionally well to RET-targeted therapies.

RET fusions are identified using next-generation sequencing or FISH, both of which can detect the abnormal rearrangement.

Your tumour will be described as RET-positive if a fusion is present and RET-negative if it is not.

NTRK (NTRK1, NTRK2, NTRK3)

NTRK genes can fuse with other genes, creating abnormal TRK fusion proteins that strongly promote tumour growth. Although rare, these fusions are important because cancers with NTRK alterations often show dramatic and long-lasting responses to TRK-targeted therapies.

NTRK testing may involve immunohistochemistry to screen for abnormal TRK protein expression, followed by FISH or next-generation sequencing to confirm the presence of a gene fusion.

Your tumour will be described as NTRK-positive if a fusion is found and NTRK-negative if no fusion is detected.

KRAS

KRAS is a gene involved in regulating cell growth and division. KRAS mutations are among the most common biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma, especially in people with a history of smoking. These mutations are important because they help predict tumour behaviour and because a specific KRAS mutation, KRAS G12C, can be treated with new KRAS-targeted medications.

KRAS mutations are detected by PCR or next-generation sequencing to analyze tumour DNA.

Your tumour will be described as KRAS-positive if a mutation is identified and KRAS-negative if no mutation is found.

ERBB2 (HER2)

ERBB2, also known as HER2, is a gene that can acquire mutations leading to abnormal signalling and tumour growth. HER2 alterations are important because targeted therapies—and ongoing clinical trials—address tumours with HER2 mutations.

HER2 testing is performed using next-generation sequencing to detect ERBB2 mutations in the tumour’s DNA.

Your tumour will be described as ERBB2-positive if a mutation is detected, and as ERBB2-negative if no mutation is detected.

NRAS

NRAS is a gene similar to KRAS that participates in cell growth pathways. NRAS mutations are more common in people who have smoked. Although specific NRAS-targeted treatments are not yet available, identifying an NRAS mutation helps doctors understand tumour behaviour and consider clinical trial options.

NRAS testing is performed using next-generation sequencing to look for mutations in the tumour’s DNA.

Your tumour will be described as NRAS-positive if a mutation is detected and NRAS-negative if no mutation is found.

MAP2K1 (MEK1)

MAP2K1, also called MEK1, is a gene involved in a signaling pathway that regulates cell growth. Mutations in MAP2K1 are important because targeted therapies directed at this pathway are being studied and may become treatment options.

MAP2K1 testing is performed using next-generation sequencing to detect mutations in the tumour DNA.

Your tumour will be described as MAP2K1-positive if a mutation is identified and MAP2K1-negative if no mutation is found.

NRG1

NRG1 is a gene that can form rearrangements or fusions that promote tumour growth. Although rare, NRG1 rearrangements are important because they may be sensitive to new and emerging NRG1-targeted therapies currently being studied.

NRG1 testing is performed using next-generation sequencing to examine the tumour DNA for evidence of a gene rearrangement.

Your tumour will be described as NRG1-positive if a rearrangement is detected and NRG1-negative if no rearrangement is found.

PD-L1

PD-L1 is a protein found on the surface of some cancer cells. It interacts with immune cells in a way that allows the tumour to evade the immune system and avoid destruction. PD-L1 is important because tumours with high PD-L1 expression are more likely to respond to immunotherapy, a type of treatment that helps the immune system recognize and attack cancer cells. Immunotherapy medications called PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors are now standard treatments for many patients with lung adenocarcinoma, especially when the tumour shows high PD-L1 levels.

Pathologists test for PD-L1 using immunohistochemistry, a laboratory method that uses antibodies linked to dyes to bind to the PD-L1 protein and make it visible under the microscope. The test measures how many tumour cells show PD-L1 on their surface and how strongly they express it. This test is usually performed on a biopsy sample before treatment begins.

PD-L1 results are reported as a percentage, representing the proportion of tumour cells showing PD-L1 staining. This is called the Tumour Proportion Score (TPS).

-

A TPS of <1% is considered PD-L1–negative or very low.

-

A TPS of 1–49% is considered low to intermediate expression.

-

A TPS of 50% or higher is considered high expression.

Some reports may also include scores for immune cells or use the Combined Positive Score (CPS), depending on the testing method used.

After the diagnosis

After your diagnosis is confirmed, your doctor will review the pathology report, imaging studies, and your overall health to create a personalized treatment plan. Treatment may include surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of these approaches.

It is important that molecular testing be performed on your tumor. Many lung adenocarcinomas harbour specific genetic alterations, such as mutations in EGFR, ALK, ROS1, KRAS, or RET, that can be targeted with highly effective therapies. Molecular testing is now a standard and essential part of lung cancer care, even in early-stage disease.

Your healthcare team may also discuss additional imaging to look for spread, pulmonary function testing to assess your lung capacity, and strategies to manage symptoms such as cough or shortness of breath. Follow-up after treatment is important to monitor for recurrence or the development of new lung nodules.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

What stage is my cancer, and what does that mean for my treatment plan?

-

Was pleural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or STAS found in my tumor?

-

Were the surgical margins clear?

-

Did the cancer spread to any lymph nodes?

-

Do I need molecular testing for EGFR, ALK, KRAS, or other biomarkers?

-

What treatments do you recommend, and what are their goals?

-

Should I see a medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, or surgeon for further care?

-

What follow-up schedule do you recommend after treatment?