Keratinocytes are the most common type of cell found in the outer layer of your skin, called the epidermis. These cells are named for the protein they produce, called keratin. Keratin is a strong, protective protein that helps make your skin, hair, and nails tough and resistant to damage. Keratinocytes form a barrier that protects your body from infections, injury, water loss, and harmful substances in the environment.

Where are keratinocytes found?

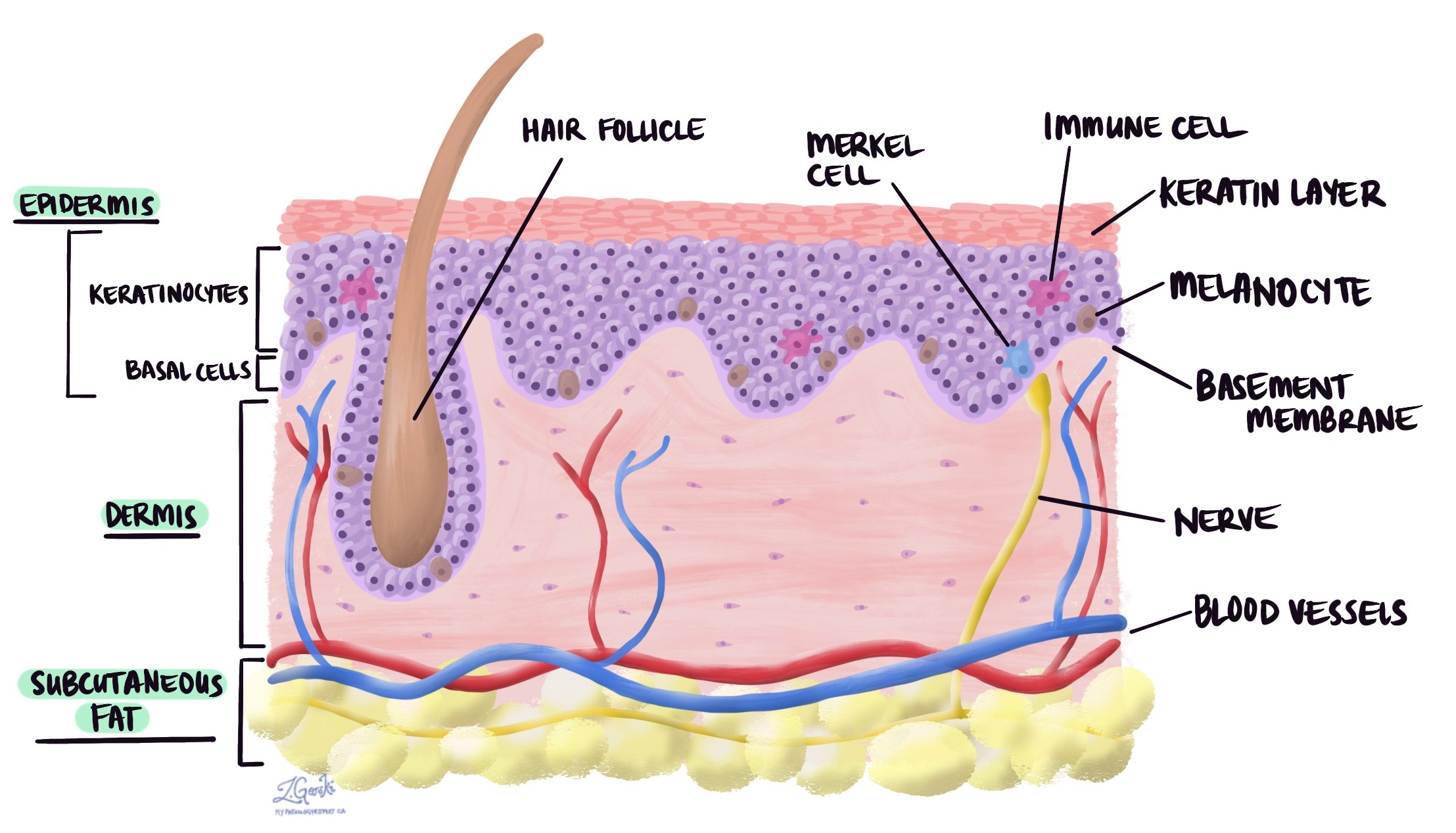

Keratinocytes make up about 90% of the cells in the epidermis. They start in the deepest layer of the epidermis, called the basal layer, and gradually move upward toward the surface of the skin. As they travel, they change shape and function, producing more keratin and eventually forming the outermost layer of dead, flattened cells that you see and feel as skin.

What do keratinocytes do?

Keratinocytes have several important roles, including:

-

Barrier protection: They create a physical wall against bacteria, viruses, chemicals, and other harmful agents.

-

Preventing water loss: They help keep moisture inside your body so your skin doesn’t dry out.

-

Repairing skin damage: When your skin is injured, keratinocytes move quickly to the wound to help close and heal it.

-

Immune defense: They can produce chemical signals that alert your immune system to potential threats.

How do keratinocytes change as they move to the surface?

Keratinocytes begin as small, actively dividing cells in the basal layer. As they move upward, they stop dividing and start making more keratin. In the upper layers, they flatten and lose their nuclei (the control center of the cell), becoming part of the tough, protective surface. Eventually, these cells die and are shed from the surface in a natural process of renewal.

What diseases or conditions affect keratinocytes?

Keratinocytes can be affected by many different skin conditions and diseases, including:

-

Skin cancers: Keratinocytes are the starting point for the two most common types of skin cancer. Basal cell carcinoma develops from keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis and typically grows slowly, often appearing as a shiny bump or pink patch. Squamous cell carcinoma develops from keratinocytes in the upper layers of the epidermis and can grow more quickly, sometimes forming a scaly, crusted growth or sore that does not heal. Both types are usually linked to long-term sun exposure and can be treated successfully if found early.

-

Psoriasis: This is a chronic autoimmune condition in which keratinocytes multiply and move to the skin’s surface much faster than normal. Because the cells do not have time to mature properly, they build up in thick layers, leading to the red, scaly patches characteristic of psoriasis. These patches may be itchy, painful, and sometimes crack or bleed.

-

Eczema (dermatitis): In eczema, inflammation damages the barrier function of keratinocytes, making the skin more sensitive and prone to dryness, itching, and irritation. Contact dermatitis, a type of eczema, happens when the skin reacts to an allergen or irritant, causing redness, swelling, and sometimes blistering.

-

Infections: Certain viruses, such as the human papillomavirus (HPV), can infect keratinocytes and cause skin warts or, in some cases, precancerous changes. Other viruses like herpes simplex can infect keratinocytes and lead to painful blisters. Bacteria and fungi can also affect keratinocytes, contributing to a variety of skin infections.

-

Autoimmune diseases: In some autoimmune skin disorders, the immune system mistakenly attacks keratinocytes or the structures that connect them to each other and to the underlying skin layers. In pemphigoid, the immune system targets the connection between the epidermis and the dermis, leading to tense blisters that form under the skin. In pemphigus, the immune system attacks the bonds between keratinocytes themselves, causing fragile blisters and erosions on the skin and mucous membranes.

Why might keratinocytes be mentioned in my pathology report?

If your pathology report mentions keratinocytes, it may be describing a normal finding (such as skin tissue in a biopsy) or explaining changes in these cells caused by a disease or condition. For example, in skin cancer, the report may describe how keratinocytes have changed in size, shape, or arrangement compared to normal cells.

Questions to ask your doctor

-

Why are keratinocytes mentioned in my pathology report?

-

Are the keratinocytes in my sample normal or abnormal?

-

If they are abnormal, what does that mean for my diagnosis?

-

Do I need treatment based on these findings?