by Jason Wasserman MD PhD FRCPC

April 28, 2023

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of cancer found in the oral cavity. It starts from squamous cells, which are thin, flat cells that form the surface lining of the mouth.

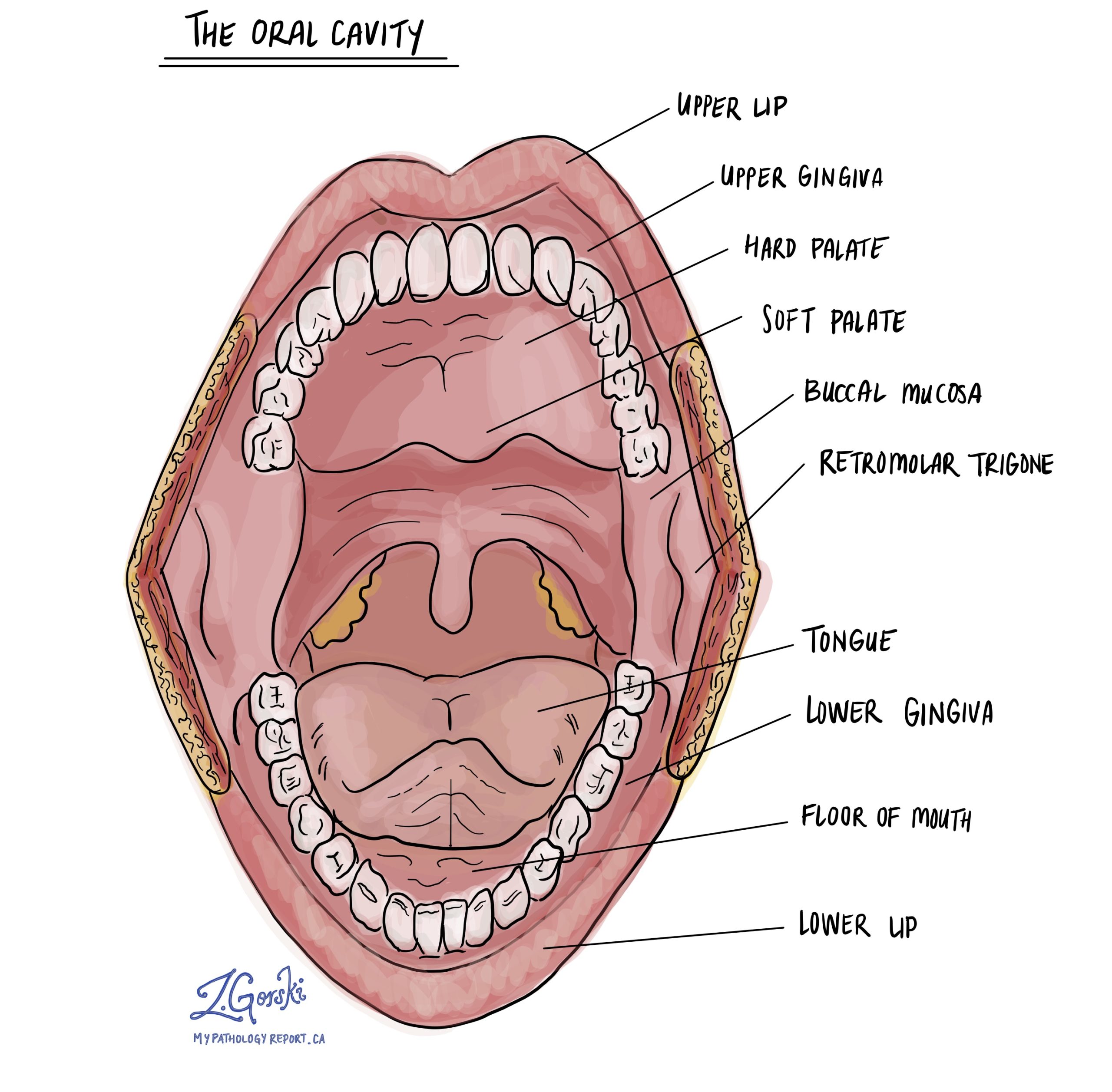

The oral cavity includes the lips, front two-thirds of the tongue, inner cheeks (buccal mucosa), floor of the mouth, gums, retromolar trigone (the area behind the last molar), and the hard palate. Cancers that arise in these areas are collectively referred to as oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma.

What are the symptoms of squamous cell carcinoma?

Early squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity may not cause any noticeable symptoms. As the tumour grows, people often notice changes in the mouth that do not heal within two to three weeks.

Common symptoms include:

-

A sore or ulcer in the mouth that does not heal.

-

Red, white, or mixed red-white patches (erythroplakia, leukoplakia, or speckled leukoplakia).

-

Pain, bleeding, or tenderness in the affected area.

-

Loose teeth or poorly fitting dentures.

-

Difficulty chewing, swallowing, or speaking.

-

Reduced movement of the tongue or jaw.

-

A lump or swelling in the neck may indicate cancer spread to a lymph node.

A healthcare professional should evaluate any persistent sore, patch, or lump in the mouth.

What causes squamous cell carcinoma?

Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity develops when the squamous cells that line the mouth undergo genetic changes that allow them to grow uncontrollably. These changes often result from long-term exposure to substances or conditions that damage the cells.

The main risk factors are tobacco use of any kind, heavy alcohol consumption, betel nut or areca nut chewing, and poor oral hygiene. Chronic irritation from dental appliances or sharp teeth, previous head and neck radiation, and a history of oral precancerous conditions, such as leukoplakia or erythroplakia, also increase the risk. Some people are at higher risk because of inherited or acquired immune problems, such as Fanconi anemia or immunosuppression after organ transplantation.

Most squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity are not caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), unlike cancers of the oropharynx (the area that includes the tonsils and base of the tongue). Because of this, HPV and p16 testing are not routinely used in oral cavity cancers.

How is this diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma is made after a biopsy from the abnormal area is examined by a pathologist, a doctor who studies tissues under a microscope to make a diagnosis.

Clinical examination

Your doctor begins by examining the mouth, tongue, gums, and neck. They look for any irregular, ulcerated, or thickened areas and check for enlarged lymph nodes. They record the size and location of the lesion and may take photographs to guide biopsy and treatment planning.

Imaging

Imaging studies help determine the size of the tumour, how deeply it extends into surrounding tissues, and whether it has spread to nearby lymph nodes or bone. Common studies include contrast-enhanced CT or MRI scans of the oral cavity and neck. PET-CT may be performed for more advanced disease to detect spread to other parts of the body.

Biopsy

A biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis. For most oral lesions, a small incisional biopsy is taken from the edge of the abnormal area. The sample is preserved in fixative and sent to a pathology laboratory for further examination by a pathologist.

Microscopic examination

Under the microscope, the pathologist looks for invasive squamous cell carcinoma. This means that abnormal squamous cells have broken through the epithelium (surface lining) and invaded the tissue underneath.

If the biopsy is small, the pathologist describes the features that can be seen in the limited sample. These include whether the tissue shows invasion, how abnormal the cells look, and whether the tumour is well, moderately, or poorly differentiated. The diagnosis of invasion is usually possible even from a small biopsy. Still, features such as depth of invasion, margin status, and perineural or lymphovascular invasion may not be assessable until the entire tumour is removed.

After the tumour has been surgically removed, the pathologist examines it in greater detail. The resection report includes the exact size of the tumour, the depth of invasion, the histologic grade, and whether perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, bone invasion, or muscle invasion is present. Margins and lymph nodes are also evaluated at this stage.

Histologic grade

Histologic grade describes how different the cancer cells look compared to normal squamous cells and how much keratin (a protein produced by squamous cells) they form.

-

Well-differentiated tumours are composed of cells that closely resemble normal squamous cells. They usually form keratin and tend to grow and spread more slowly.

-

Moderately differentiated tumours show greater variation in cell size and shape, form less keratin, and are more likely to invade nearby tissue.

-

Poorly differentiated tumours look very different from normal squamous cells, lack keratin formation, and tend to grow and spread more aggressively.

Your pathology report will include the histologic grade because it helps predict how the cancer may behave and guides treatment planning.

Depth of invasion

Depth of invasion refers to how far the tumour has grown beneath the normal surface of the mouth. The measurement is expressed in millimeters and is made from the basement membrane down to the deepest point of tumour growth.

The epithelium is the thin layer of squamous cells that lines the surface of the mouth. It rests on the basement membrane, a delicate barrier that separates the epithelium from the stroma, the underlying connective tissue that supports it. When squamous cell carcinoma develops, cancer cells break through this barrier and grow downward into the stroma.

Pathologists measure the depth of invasion from the basement membrane of the nearest normal epithelium adjacent to the tumour down to the deepest point of invasion. A greater depth of invasion means the tumour has penetrated further into the tissue and is more likely to spread to the lymph nodes. Depth of invasion is one of the key measurements used to determine the T category of the tumour for staging.

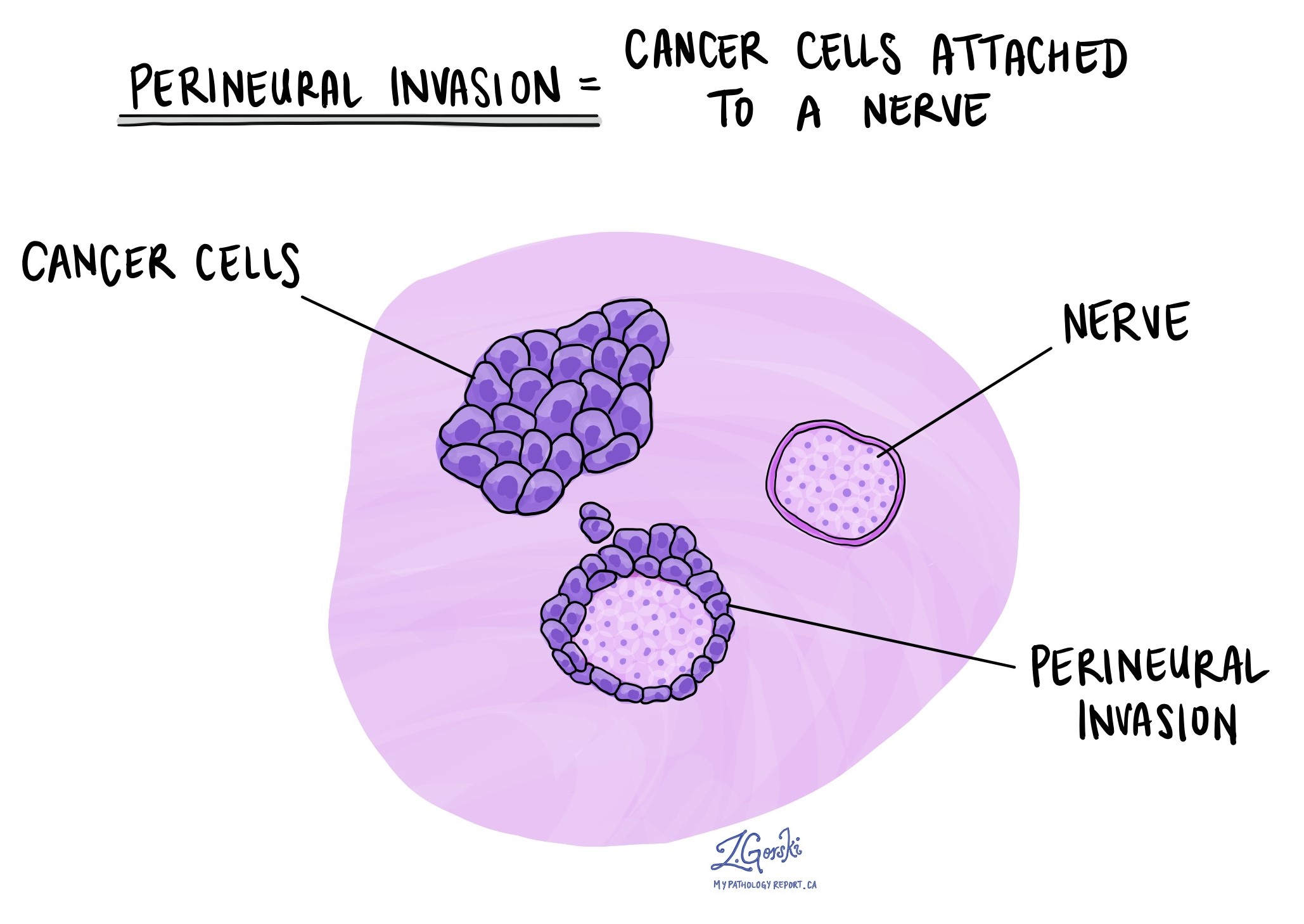

Perineural invasion

Perineural invasion (PNI) means cancer cells are growing along or around a nerve. Nerves are small structures that carry signals for sensation and movement. When tumour cells travel along these pathways, there is a greater risk that the cancer could return after treatment or spread to nearby areas. Pathologists recognize perineural invasion when tumour cells are seen encircling or tracking within a nerve under the microscope.

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) means that cancer cells have entered lymphatic channels or blood vessels near the tumour. Lymphatic channels are tiny tubes that drain fluid and carry immune cells, while blood vessels carry blood throughout the tissues. When tumour cells are found in these channels, there is a higher risk that cancer will spread to lymph nodes or distant organs. Pathologists may use special stains to make these small channels easier to identify.

Margins

Margins refer to the edges of tissue removed during surgery. After the specimen is received, the pathologist inks the outer surfaces and examines multiple sections under the microscope to see how close the tumour comes to the edge.

A margin is considered negative when no cancer cells are visible at the edge, indicating that the tumour was likely removed completely. A margin is called positive when cancer cells are present at the edge, which suggests that some tumour may remain. Some reports also use the term close margin for cancer found within a few millimeters of the edge. Close or positive margins may lead to a recommendation for further surgery or radiation therapy.

For oral cavity tumours, margins are described as mucosal (surface), deep soft tissue, and when bone is removed, bone margins.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped immune organs located throughout the body. They filter lymphatic fluid and help the body fight infection. In the head and neck, they are grouped into levels I through V on each side of the neck.

Because squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity can spread to these lymph nodes, surgeons often remove them during an operation called a neck dissection. The extent of dissection depends on the location and stage of the tumour.

The pathologist examines each lymph node under the microscope to see if it contains cancer cells. The report includes the number of lymph nodes examined, the number that contain cancer, the size of the largest tumour deposit, and whether there is extranodal extension, which means the cancer has broken through the outer capsule of the node into nearby tissue.

The presence of cancer in lymph nodes or extranodal extension is an important part of staging. It helps determine whether additional treatment, such as radiation or chemotherapy, will be recommended after surgery.

PD-L1

PD-L1 is a protein that helps cancer cells hide from the immune system. Testing for PD-L1 may be performed when the cancer cannot be removed surgically, has come back after treatment, or has spread to other parts of the body.

The PD-L1 test result is given as a Combined Positive Score (CPS), which measures the proportion of tumour and immune cells that express PD-L1. A higher CPS score may indicate that the cancer is more likely to respond to immunotherapy drugs such as pembrolizumab.

Pathologic stage

The pathologic stage describes how far the cancer has spread at the time of surgery. It is based on the TNM system, which includes the primary tumour (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastasis (M).

The T category is determined by both the greatest dimension of the tumour and its depth of invasion. Small tumours confined to the surface have a lower T category, while those that invade deeper tissues, such as bone, muscle, or skin, are assigned a higher T category.

The N category is based on whether lymph nodes contain cancer, the number involved, their size, and whether extranodal extension is present.

The M category refers to distant spread beyond the head and neck region and is typically determined by imaging studies rather than by the pathologist.

The final pathologic stage combines the T, N, and M categories (pT, pN, and pM) to form an overall stage group. Staging information, along with margin status, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and histologic grade, is used to guide treatment and prognosis.

What happens after the diagnosis?

After diagnosis, your healthcare team reviews your pathology report, imaging studies, and overall health to develop a personalized treatment plan. The team often includes a head and neck surgeon, a radiation oncologist, a medical oncologist, and a pathologist.

For most people, surgery is the primary treatment. The operation usually involves removing the tumour with an adequate margin and removing or evaluating lymph nodes in the neck.

If the tumour has high-risk features such as perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, positive or close margins, extranodal extension, or deep invasion, additional treatment with radiation or combined chemoradiation may be recommended.

For advanced, recurrent, or metastatic cancer, systemic therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy (including PD-L1–directed checkpoint inhibitors) may be considered.

After treatment, patients are closely followed with regular oral and neck examinations, as well as periodic imaging. Speech, swallowing, dental care, and nutrition are key parts of recovery. Avoiding tobacco and alcohol, maintaining good oral hygiene, and consistent dental and medical follow-up help reduce the risk of recurrence and support long-term health.

Questions for your doctor

-

Where exactly in my mouth did the cancer start, and how large is the tumour?

-

What is the depth of invasion of my tumour?

-

Did the report mention perineural invasion or lymphovascular invasion?

-

Were the surgical margins negative, or is additional surgery or radiation needed?

-

How many lymph nodes were removed, and did any contain cancer or show extranodal extension?

-

What is my pathologic stage (pT and pN categories)?

-

Was PD-L1 testing performed, and could I benefit from immunotherapy?

-

What treatment options do you recommend, and in what order should they be done?

-

How will speech, swallowing, and dental health be managed after treatment?

-

How often should I have follow-up visits and imaging studies?